Aotearoa New Zealand is at a crossroads in its response to how our built environment manages climate change. Jo Bates speaks with architects Rich Naish, Guy Marriage and James Solari about where to from here.

One word in the Environmental Defence Society’s (EDS) recently released, 95-page working paper could be the most informative on how Aotearoa New Zealand’s built environment takes shape in light of climate change.

The ‘if’ in the ‘if done well’ of the EDS’ Principles and Funding for Managed Retreat presents the cliffhanger in how managed retreat is approached. ‘If’ we design and build better to allow people and nature to flourish. Or not. Architects’ skills in understanding the land and the challenges and opportunities it presents have the potential to replace ‘if’ with ‘when’. The report has implications for the Climate Adaptation Bill, which the government is expected to introduce into Parliament later this year.

The bill will impact every New Zealander, and not through cost alone. “The wider policy issue is what we should be planning for over the next 20 years — low-carbon architecture, natural hazards, coastal erosion — all the effects of climate change.

It’s yet to be defined by the proposed bill,” says RTA Studio’s Rich Naish. “It’s going to be a fraught process that costs billions of dollars, but international precedent shows that managed retreat will be more cost-effective than an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff when disaster strikes,” he says.

Managed retreat is the deliberate and coordinated relocation of people, buildings, infrastructure, and assets of cultural significance, to avoid damage.

Ideally, this adaptation response is pre-emptive and includes avoiding risk at the outset, such as applying architecture to design buildings that mitigate natural hazards.

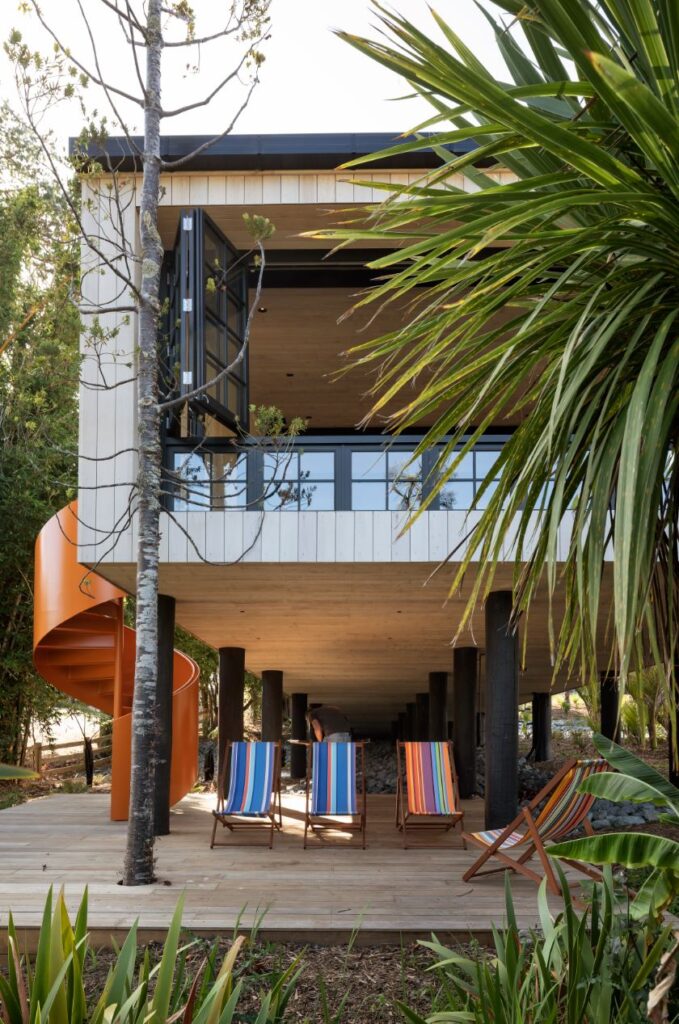

Naish’s own holiday home is a case in point. Built over a floodplain on a piece of land that no one else had the fortitude or technical knowledge to tackle, it sits on poles above a dry, rocky river bed that reliably runs in a significant downpour. “It’s about being aware,” says Naish of the design at Buckleton Beach, Tāwharanui Peninsula.

Naish cites another project by RTA Studio that takes a preventative, restorative, and sustainable approach to site. Fisher & Paykel’s global headquarters in Penrose, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, is designed to float above the ground, and is a socially sustainable blueprint for an office-and-product development building on post-industrial land, says Naish.

“Stormwater is allowed to flow across the site. There’s a pond for stormwater and we’re regenerating the land with original flora that grew there pre-European times. The design considers te ao Māori and is about restoring and humanising the land,” he says.

Referring to the recent Cyclone Gabrielle-inflicted deluge of the Esk Valley, which has a history of flooding, Guy Marriage, architect and lecturer in construction at Te Herenga Waka, Victoria University of Wellington, warns against rebuilding like with like.

“It’s the stupidest idea ever. Insurers may say we need to build the same as before, but that makes no sense. No one in the Esk Valley should be rebuilding a house on the flat. Build on posts or piles to be above the ground, or on a rise at the edge of the valley. Being 2m higher than the surrounding soil would protect you from 90 per cent of future weather events,” he says.

Resilient design is a key component to any future response, says Wellington architect James Solari. “Regional and rural parts of the country have been battling weather events for generations. As city centres now face similar crises, my hope is that we can build more resilience by combining our expertise across multiple design disciplines.”

Climate change is upon us and we need to be prepared for what’s ahead, says Solari, who was raised on a 450-acre farm

in Otama, near Gore, on the fertile floodplains of the Mataura River. “The river is something we respect as it contributes to the fertility of the land. It is a floodplain and will always be subjected to flooding — sometimes we lose crops — but the floods bring more new soil, which have produced two world-record wheat crops over the past 16 years. The house, built in the 1920s, is on piles, and while it has been surrounded by floodwaters, it hasn’t flooded,” says Solari.

When done well, managed retreat can result in new, better and more resilient buildings and communities. The alternative — unmanaged retreat — will result in inequities, entrapping those without the means to relocate. When actively seeking positive societal and environmental outcomes as part of managed-retreat, Aotearoa has the opportunity to pivot to transformational retreat. There are no ‘ifs’ in this approach.