This monopitch, minor dwelling by Assembly Architects was inspired by Roman domus, tripped up by gladiatorial battles against local design parameters, and boasts a tasteful play of translucency and light.

Approximately 12 years ago, business and life partners Louise and Justin Wright packed up their three children and their belongings and moved from Wellington to the outskirts of Arrowtown.

The shift was followed by the purchase of a site in a large subdivision. There, the Assembly Architects directors built their family home. The materials, design, and construction programmes were simple, and sought speed (a mere 16-week build), and adherence to a tight budget.

One of the early decisions the Wrights made was to place the house at the back of the site, leaving, to the north, the generous garden and delightful views of The Remarkables.

The site — with its driveway along the eastern boundary — is a nearly perfect, slightly rotated rectangle whose length runs from north, by the main road, to south-west.

“The idea was that eventually we would have a ‘stage two’ building at the front, whether that be a garage, or whatever,” says Justin, “and we developed the whole garden of the property with that in mind.”

According to the Wrights, the original planning of the house around the courtyard was inspired by their time spent in Rome, and, more specifically, Roman traditional single family dwellings known as domus.

Instead of placing the dwelling in the middle of the land, looking outwards, “We pushed the buildings outwards, looking inwards,” Justin explains. “So we opened up the centre to have as much sun as we could coming into the middle of the site, keeping the buildings on the outside part of that.”

In Roman times, a type of atrium with a water feature/repository tended to act as the centre of the house, a sunny spot onto which most of the other private spaces looked.

Whereas the courtyard of a domus would have normally been surrounded by built structures on all four sides, in this site, the evergreen Portuguese laurel has been used to help define an open-air rectangle, with two separate buildings along the north and south.

Stage two was nearly 10 years in the making, ten years that gave the couple a chance to develop this Italian-inspired landscape (in layout rather than in material or aesthetic allusions); get acquainted with the climatic condition; and — in part due to lockdowns — better understand what was required from a new interior.

According to Louise, this second structure — which it was initially thought would be garaging or possibly storage — became a minor dwelling with an impressive number of uses: guest bedroom, carport, office, and ample storage for all the accoutrements expected of any respectable Central Otago suburban home.

“The ski gear, the bikes, the firewood,” says Louise, “all those things are hidden away” — whereas the open carports give a clean, open feel to the roadside façade.

The design language here is entirely different from that of the original abode. It is more up-spec — reflecting a different point in the couple’s successful architectural practice — and also reveals some of the craft and material intent they have learned along the way.

“It is a similar batten system to what we did in the Abodo showroom,” explains Louise, referencing the award-winning retail space they designed in Cardrona for the timber company.

“This has got a similar batten proportion and layout,” says Justin, while pointing out the design value of the New Zealand–made product, which wraps much of their new space.

Another reason for the vastly different aesthetic was the desire to articulate any new structure as an addition (or aggregate) rather than a ‘Disneyfied’, pastiche version of the past.

“It is a different structure and different materialities. In Arrowtown, you kind of want to articulate forms and differentiate the gable and lean-to forms and different materials to express that those things have been aggregated as stages over time,” says Justin.

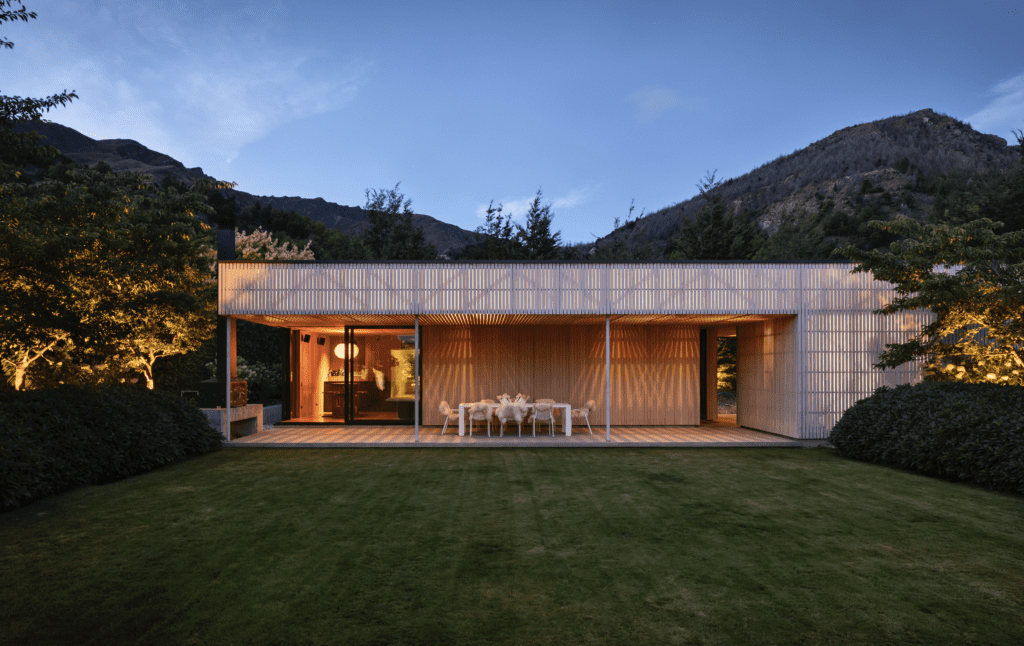

The architects opted for a timber-clad monopitch structure with a generous veranda held up by elegant thin pillars and playfully expressing negative spaces of timber and curved openings.

This strongly ‘different’ form had its detractors. The local homeowners’ association has stringent design rules that called for adherence to local vernacular forms and material, and the straitjacket of the ‘gable’ is one of those.

However, having lived on the site for over a decade, knowing its climate and sight-lines to the alpine peaks, and knowing their neighbours well, the Wrights felt the gable was too simplistic a solution, and one that would end up infringing on the privacy of those around them.

The homeowners’ association said the build had to have a gable, but, as Justin jokes, “Nothing gets an architect quite as motivated as being told that you can’t do what you want to do in your own home project, particularly when your neighbours have said, ‘Hey, that’s the much better result.’ So, yeah, we persevered.”

It took about two years before construction could begin. “We couldn’t be happier,” says Louise. Although the plan is eventually to either to let the domus or move there once the kids have fled the nest, the new space is used every night for guests or movie nights or as a hang-out zone.

Given that the structure is placed directly in front of the main house, the Wrights opted for a little touch of playful magic in the form of translucency and glow.

“For us, the house is by far the most important elevation as it is what we’re looking onto,” Louise says. “It’s quite a big roof form, but its internal thermal envelope is only about 65 square metres.”

This gave the couple the idea of cladding the non-thermal envelope with a slightly translucent polycarbonate with the timber façade on top — “Timber board on a horizontal batten on Twinwall that’s about 8mm thick,” says Justin — then a series of internal lights that can be controlled remotely and their colouration fine-tuned according to whatever nature is doing.

“When we have those days with fresh snow on the ground here … it’s all quite something,” says Louise, “It’s very dramatic.”