Set among protected wetlands on the Kāpiti Coast, this rural home by Studio Pacific Architecture uses sculpture, environmental nous, and scale for a living environment that is full of heart.

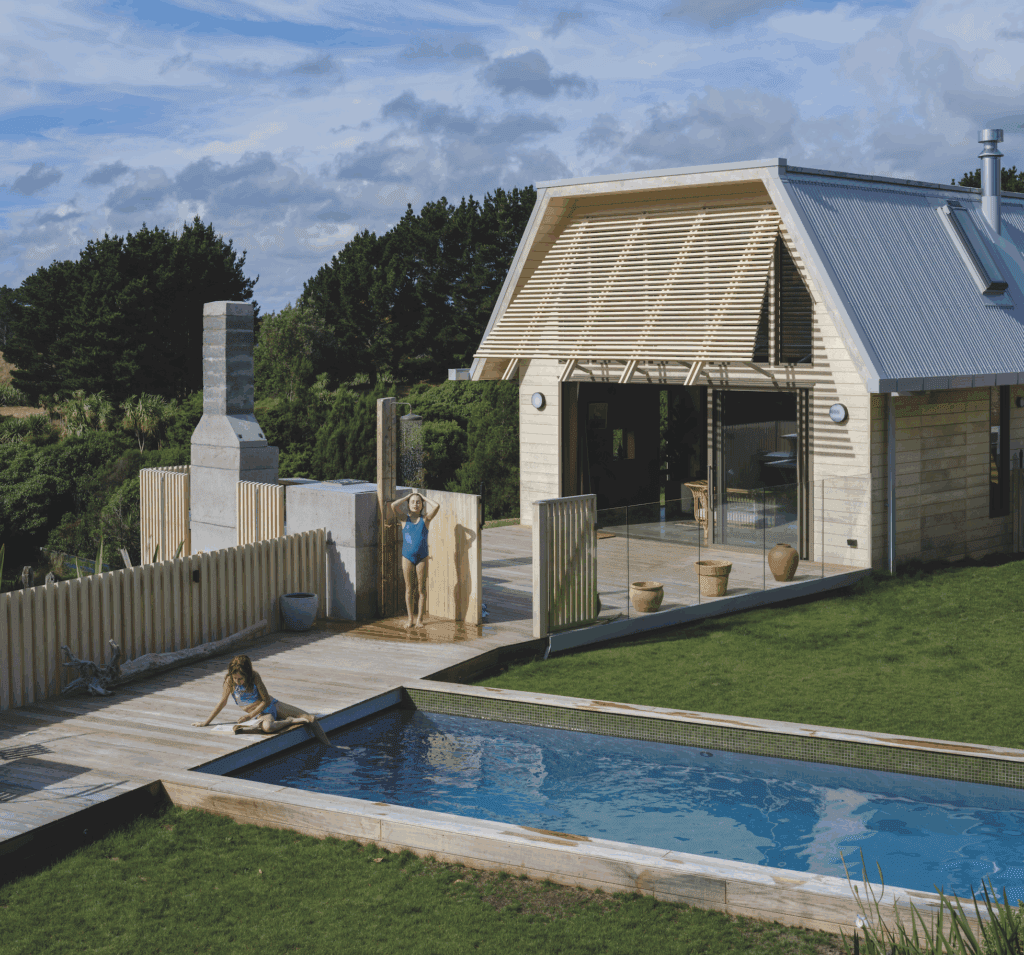

Perched on the undulating dunes of New Zealand’s Kāpiti Coast, just a kilometre from the sea and embraced by protected wetlands, Kāpiti House by Studio Pacific Architecture is a retreat that celebrates life within the landscape.

For Stephen McDougall, founding principal of the practice and the home’s owner, the project is deeply personal. “The whole site is part of the house, and the house is part of the whole site,” he reflects.

The site was purchased just after the country entered a Covid-19 lockdown. The land came with a modest 1980s cottage — later shifted downslope to make way for a new house — orchards, and an expansive permaculture garden.

For Stephen and project architect Victoria Wright, the aim was never just a house but a living system — an architecture intertwined with food production, wetlands, horses, solar energy, and a deliberate rhythm of retreat that allowed the owners to go from a highly social city life to something slower.

The form — nicknamed the ‘Japanese barn’ — reads at once as pragmatic and poetic. Its roof sweeps low, doubling as a wall, the gesture born from a practical constraint: solar control and the 60-degree threshold in the building code for roof classification. Yet, its simplicity echoes mansards and rural woolsheds with hints at Herzog & de Meuron’s retail experiments in Tokyo’s Omotesando and Aoyama.

“We never went looking for barns,” Stephen admits, “but there was something in using the roof as the wall. That became the trigger.” “Material selection was equally critical,” Victoria elaborates. “We wanted a low-carbon palette, hardboard made from timber waste, recycled rimu for cross walls, concrete with 35 per cent fly ash replacing cement, and an uncoated acetylated pine exterior. Every choice was deliberate; every finish pared back.”

The result is a quietly striking, timber-lined volume whose presence is softened by its embeddedness in the land.

“The house is sort of sitting on a terrace that we cut into the hill,” says Stephen. “It runs perpendicular with the two main ridge lines that run through the landscape.”

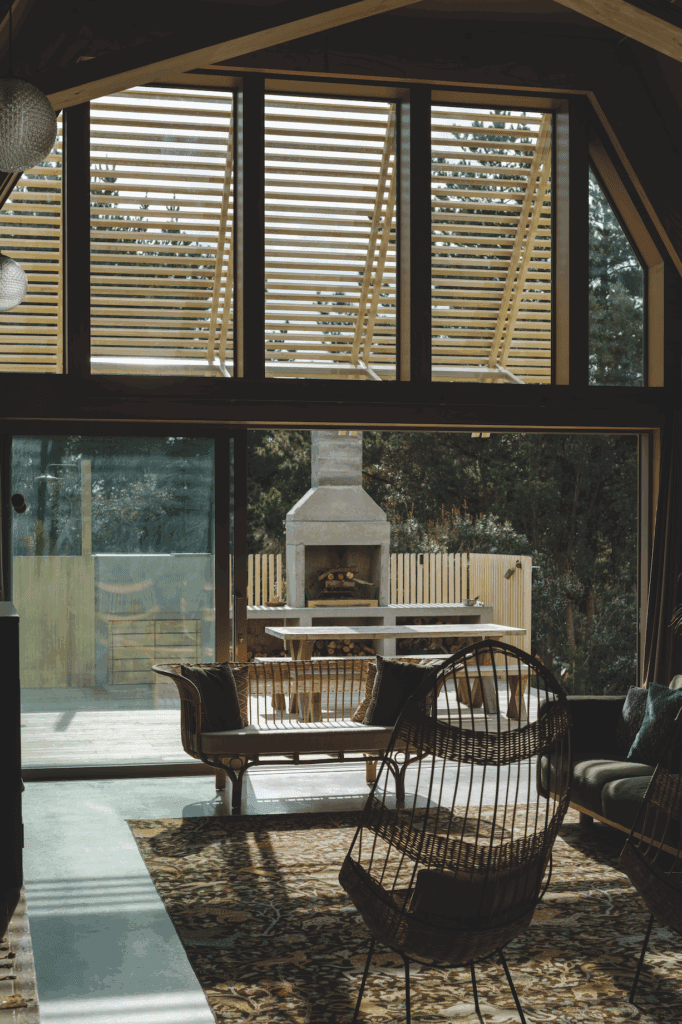

If the landscape holds the project’s ethos, the living room contains its heartbeat. A soaring space, approximately five metres high, it carries the proportions of Studio Pacific’s earlier Park House but feels loftier due to its flat ceiling and continuous timber wrap. Eight NelsonPine LVL portals march rhythmically along the entire home’s span, while four cross-braces infuse the living space with a sculptural quality and bring human scale to the cavity.

“People come in and just stop,” Stephen recounts, remembering how a loquacious, “long-time friend … stood there completely lost for words,” while another described it in a letter as “like being inside a carefully folded brown paper bag of profound tranquillity”.

The metaphor is apt. Long walls and ceilings are clad in warm hardboard sheets, their simplicity disrupted only by secret doors camouflaged within recycled rimu cross walls. There is no plasterboard; surfaces are left largely untreated, with just a clear protective coat to preserve the tone and tactility of the materials.

Simple detailing, restrained junctions, and honest finishes allow the structure to take the lead, say the architects. The only slick of paint is on the coloured leading edges of doors — deep blues in the main house, golds in the tower — echoing bathroom tile work.

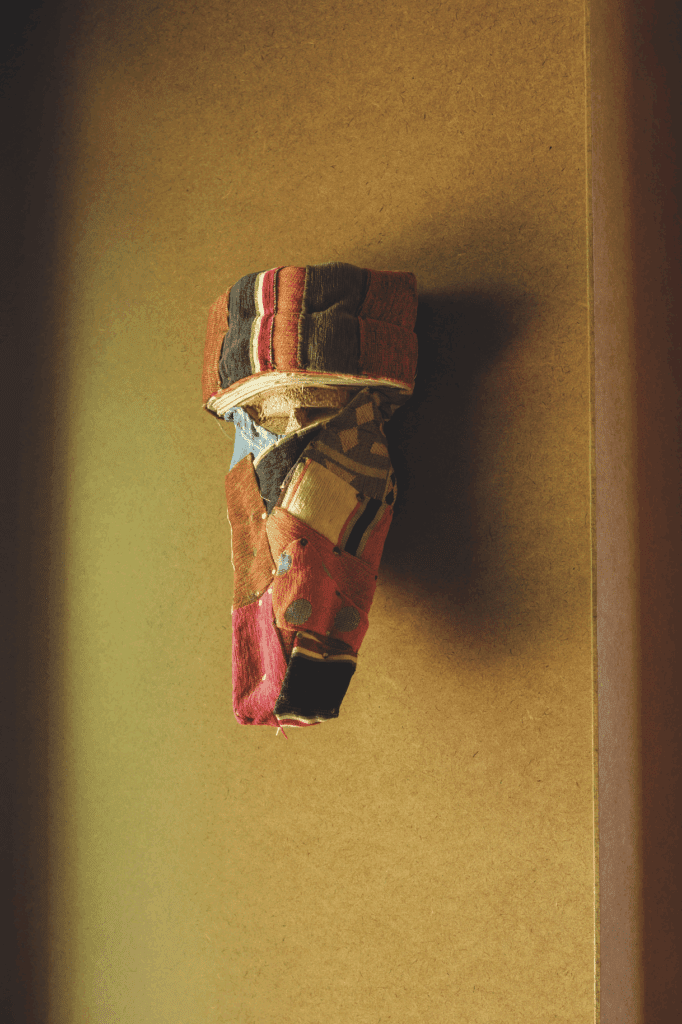

Rather than sleek minimalism, the interiors lean towards a personal, collected warmth. “We didn’t want purchased things just dumped in,” says Stephen.

Antique Afghan rugs, Czech glass spheres, and mid-century New Zealand cane chairs (originally made by the Blind Institute) populate the rooms.

Wardrobes are veiled with textiles — Laotian hemp drops, Indonesian batiks, Tunisian embroideries — each room inflected with a slightly different curtain hue: burnt orange, deep blue, moss green. “They relate to the tiles and to the land outside,” Victoria notes, “subtle but grounding.”

Right behind the open-plan kitchen and before the bedrooms, there is a loft that is accessible via stepladder. It provides a perch for teenagers or a yoga nook for Stephen’s partner.

Outside, on a second structure, the team have erected a self-sufficient ‘tower’ or ‘keep’ for extended whānau.

Everywhere, the architecture privileges generosity of volume over proliferation of rooms. “It’s incredibly simple,” says Victoria. “Four doors in the whole main house; one in the tower. That’s it.”

Sustainability is an integral part of the construction. The house is externally insulated, lined internally with wool, and paired with thermally heavy drapes. Solar panels — discreetly tucked beneath the deck — power underfloor hydronic heating and hot water. Seven water tanks and a bore make the home independent.

Stephen says that, in theory, the house can be run entirely off-grid. It uses passive housing ideals, although it does not have the certification.

This ethos extends outwards. Half of the 16-acre property is protected wetland; the other half hosts horses, orchards, and a permaculture garden painstakingly built from sandy soil into 600mm of rich compost.

“We’ve grown that from sand,” Stephen notes — two and a half years of worms and hard work.

For all its embedded systems, what strikes visitors most about the property is the atmosphere. The living room, with its five-metre loft and timber envelope, conjures calm.

Guests describe an “immediate comfort” and a “visceral response” upon entry. “It’s not a pavilion, not a gable, not black board and batten,” Stephen says, referencing the ubiquity of contemporary rural houses. “Maybe that’s why people respond so strongly; it’s different.”

Words: Federico Monsalve

Images: Simon Devitt

Judges’ citation

Cathedral-like, yet inviting and cosy. Intensely architectural in its materiality and forms, yet tactile and lived-in in its furnishings and palette. Add to that a sustainable ethos and you have a living space that will look after its inhabitants for generations to come. This Japanese-inspired barn celebrates materials while being intently human-centric.