On a residency in Canada’s icy, far-flung Fogo Island, artist Kate Newby finds art and architecture being used to chart a new future

The artist Kate Newby is in her sickbed. You can’t blame her: outside it’s been minus 18 degrees and in her studio, cups of water are freezing. She is in a saltbox house on the very edge of the earth (quite literally, if you’re a member of the Flat Earth Society) called Fogo, a tiny island northeast of Newfoundland, Canada. Here, Elizabethan English and old Irish dialects still inflect the accent and the towns have strange, lonely names like Tilting, Seldom-Come-By and Farewell. There are seals, whales, caribou and coyotes, and 11 little communities with a total population of 2700.

To be in residence here seems perfectly suited to Kate, whose art gently interrogates its surroundings, and is usually site-specific because “I like work that has a conversation with the things around it.” ‘Crawl out of your window’, which won 2012’s Walter’s Prize, was an unearthly pale-blue pool, pitted with puddles and scattered with leaves and bottle tops, covering a large area of floor at Auckland Art Gallery. It was called “radical but reserved” by the judge. ‘How funny you are today, New York’ consisted of two space-age coloured rocks nonchalantly hanging out in a park in Brooklyn.

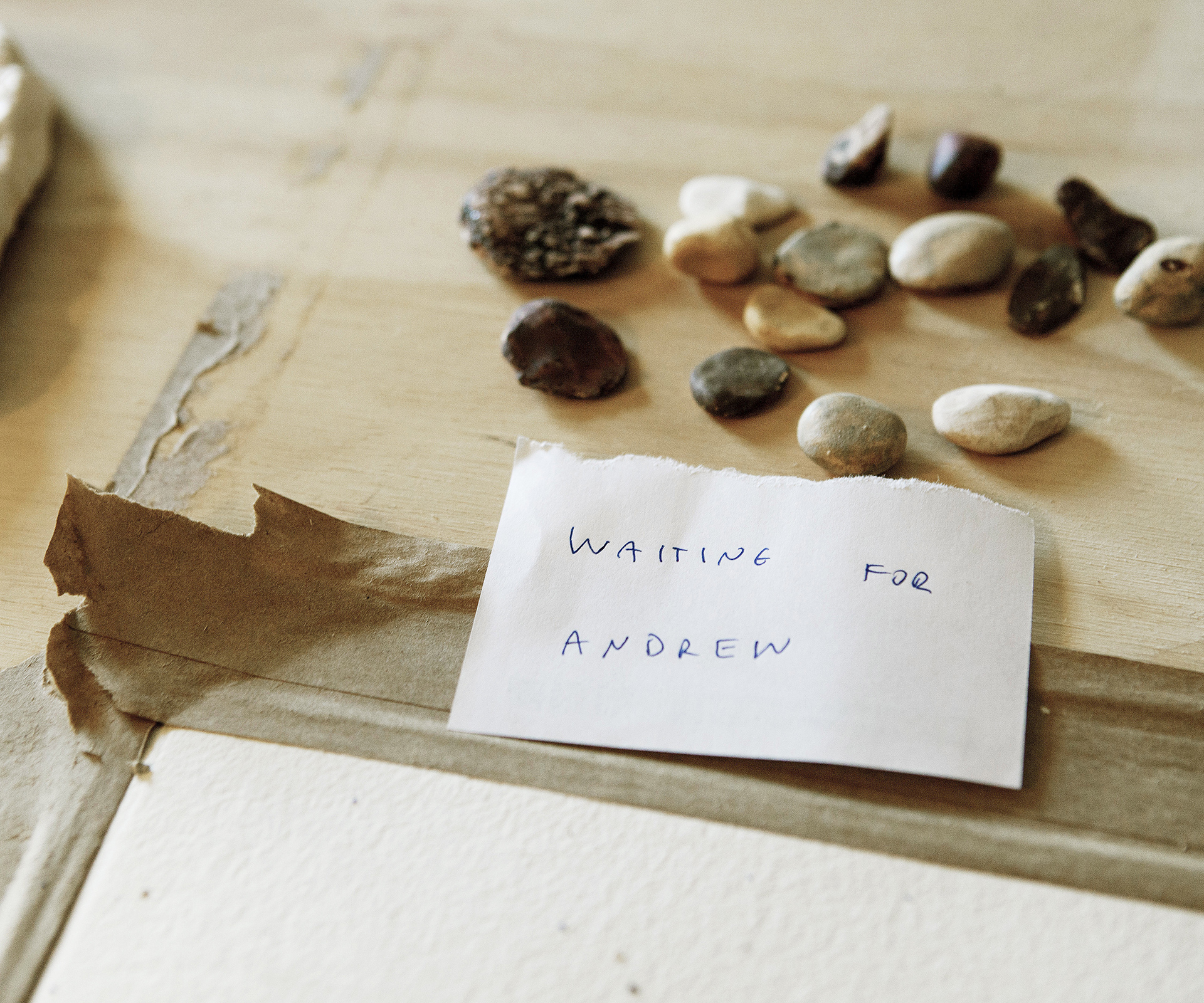

The Fogo Island residency comes with a car, a restored historic home in Shoal Bay and a studio on the village’s coastline, one of four spectacular new buildings dotted around the island. Named Tower, it is a misshaped diamond of vertical black clapboard designed by former Fogo Islander and now Norway-based Todd Saunders. It is windowless aside from a giant skylight on the ceiling, with two storeys that twist like a waist. Kind locals helped her lug her materials the 15-minute climb from the road to the studio. Her days are spent working with quiltmaker Linda Osman and geologist Paul Dean, firing rocks out of clay and porcelain at a kiln in a church and revelling in the lyrical lingo and culture.

She’s been into rocks for a while, she says, and now finds herself in rock nirvana. Here, rocks are everywhere, literally and metaphorically. They turn up in stories and appear in ceremonies (one marks an occasion by turning a rock); locals warm their beds with rocks, make Killick anchors out of rock and even, in little heritage town Tilting, name their rocks.

For around four centuries (after killing off the original Beothuk people), Fogo Island’s English and Irish settlers fished for cod. Then, suddenly but predictably, the cod ran out and in 1992, the government placed a moratorium on fishing. Life as the people knew it was over. The island needed an angel, ASAP, and found one in the form of Zita Cobb.

The daughter of illiterate Fogo Islander fishers, Zita Cobb spent her first 17 years here, in a saltbox without power or electricity, before heading off to the mainland to make her frankly stupendous fortune as the head of a fibre-optics company. By the time she reached her 40s, she was one of Canada’s richest women, and she cashed up and sailed the globe. Already a veteran philanthropist (or, in her own terminology, a social entrepreneur), she turned what was meant to be a brief visit home into a resolution to stay there until she fixed it. Her tools in this mission? Art and architecture.

That art has transformative social power seems a radical idea in a rural purlieu such as this. But art has saved this place once before. In the 1960s, the islanders faced resettlement on the mainland when the Canadian government decided to centralise its services. At that time the island’s villages were disparate, so a university in Newfoundland and Canada’s National Film Board collaborated on a series of short films that exquisitely depict life on the island. Once the villagers saw their reflections in each other, they got organised. “For the first time, the communities talked to each other, then they rallied together and said, no, we don’t want to move, and they stood up to the government,” says Kate. The Fogo Process has since been used elsewhere in America, and in Asia and Africa, as a means to address repatriation.

Zita Cobb was a child at the time of the process (she appears as a wedding guest in one of the films) and now, almost 50 years later, she is more or less single-handedly spearheading her own, updated version of it. Her aim is to use art to provide the same level of awareness and reflection that the little black-and-white films afforded her parents in the 60s.

Then there is the Fogo Island Inn in the capital Joe Batt’s Arm – no ordinary inn, but a luxury eco hotel-sauna-cinema-library-art gallery, long and white, on stilts, with kooky, skinny windows. The interior is decorated in traditional handcrafted furniture and happy-coloured quilts. Not only a generator of jobs but also owned by the community, “this inn is a phenomenal building and enterprise,” says Kate.

On the benefits of her presence on the island, Kate says, “there’s definitely something to be said for artists coming here and making work, and the benefit for me is immediate, direct research into a new place.”

Text by: Julie Hill. Photography by: Steffen Jagenburg.