New Zealander Rebecca Roke’s book, Nanotecture, extols the virtues of designing small

What stimulated your interest in nanotecture, and made you want to write this book?

Rebecca Roke: I’ve always been drawn to how small buildings are designed – especially the way in which they encourage experimentation with materials at a relatively low cost as well as demanding a high level of design resolution. The smaller a building is, the more we notice its detailing. I think in design, a tighter brief often gives rise to highly creative design responses. Nanotecture brings to life the great variety available for this architecture/design typology.

It seems that designing small (and, in some cases, whimsically) offers a strange freedom. Is this what you found about some of the projects in the book?

Small buildings are definitely a canvas for expressive designs: partly because of their limited size and partly because the functions are not usually as complex as what is required for larger works. Projects like PlayLAND for example, take the simple, readily available component of a child’s pool float and turn it into a spatially rich public installation that is full of colour and appeal.

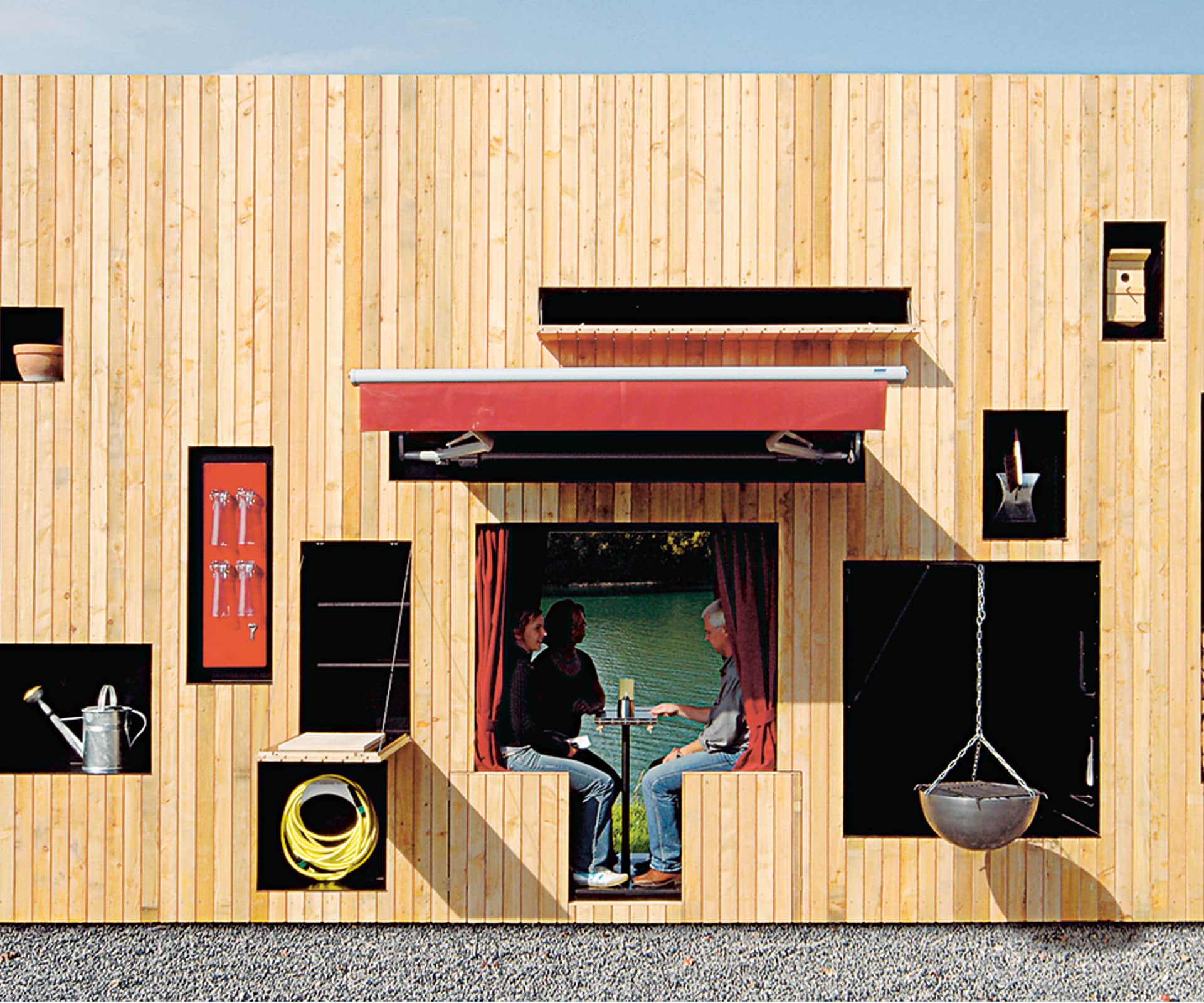

Similarly, a project such as Walden suggests playful yet relevant structures that allow for us to dwell in nature, simply, yet with a variety of delightful accessories – its cauldron, roof-top terrace, fire etc. I think that small buildings increasingly express people’s desire for sustainable yet nourishing places in which to dwell, think, or relax.

Average house sizes in many countries are ballooning. Why do you think this is, and is your book a conscious counterpoint to this inflation?

Housing and site costs are increasingly inaccessible proportional to earnings in places such as New Zealand, Australia, the UK and the USA. I think the tiny house movement is a kind of thoughtful reaction to overconsumption – of space and materials – and Nanotecture includes examples that express this stance. Essentially, it’s about leading a more simplified life with the associated reduction in building footprint.

A lot of these homes come about once owners or designers decide to assess what is really necessary and do away with brobdingnagian proportions. Projects like Hello House in Melbourne or the Mirrored Tree House in Sweden are examples where designers have used a simple material palette to transform a small space into something inspiring – and that engages with the proportion and context of the site. As long as the pressure on cost and accessibility for housing continues, I think it will force people to continue to find creative ways that they can live well.

You’re a New Zealander living in London, which is facing a housing crisis that has some similarities to what we see in Auckland. Do you see hopeful signs of architecturally-led solutions to these problems?

The spatial pressure in London is immense. Though there is notional support for increased housing of high quality, the real result and longevity of what is being built is highly variable and most often depends on the outlook of the developer. In order to really make an impact on what is built, it will require a more holistic reassessment on the part of such developers to change the status quo and incorporate proven strategies for good design at high density – especially in urban centres.

Images from: Nanotecture, Tiny Built Things, published by Phaidon.

[related_articles post1=”44373″ post2=”52441″]