A clifftop Waiheke location provided a fascinating challenge for architect Wendy Shacklock – to create a home that was both comforting and exciting

It was a home that began with a name that sounds terribly romantic – Te Kohanga, the Maori word for nest – until you remember that nests are as precarious as they are protective, and prone to getting blown out of trees in the wind. But creating a balance of these elements also made for a fascinating architectural challenge for Wendy Shacklock and her clients, Brian and Sally McKibbin. How to create a home on a vertiginous Waiheke Island clifftop that felt comforting and adventurous at the same time?

The process started early, with Shacklock helping Sally and Brian search for an appropriate site. It is rare to find an available piece of land this magical on Waiheke Island these days, but this one not far east of Oneroa turned out to be hidden in plain sight. “This place was a wilderness,” Brian says, “full of old water tanks and scrub.”

[quote title=”This place was a wilderness” green=”true” text=”full of old water tanks and scrub” marks=”true”]

Its incredible views were also mostly obscured. Fourteen truckloads of rubbish were removed from the site, which also had an old, undistinguished house on it that Brian and Sally stayed in while plans for their new home were hatched.

The McKibbins were moving here after selling their previous Waiheke home, a Mediterranean-style residence they had designed themselves with a draftsman. It had large verandahs for outdoor living and an abundant garden. This time they wanted something different, but they weren’t terribly specific in their brief to Shacklock about just how different it should be.

“We wanted a home that was full of surprises, and I think that’s been achieved,” Sally says. “We employed an architect, so [we had to have] confidence in her, because that’s what you’re paying for.” When it came to specifics, the couple said they wanted three bedrooms, as well as the ability to entertain a crowd of 50 if they felt like it.

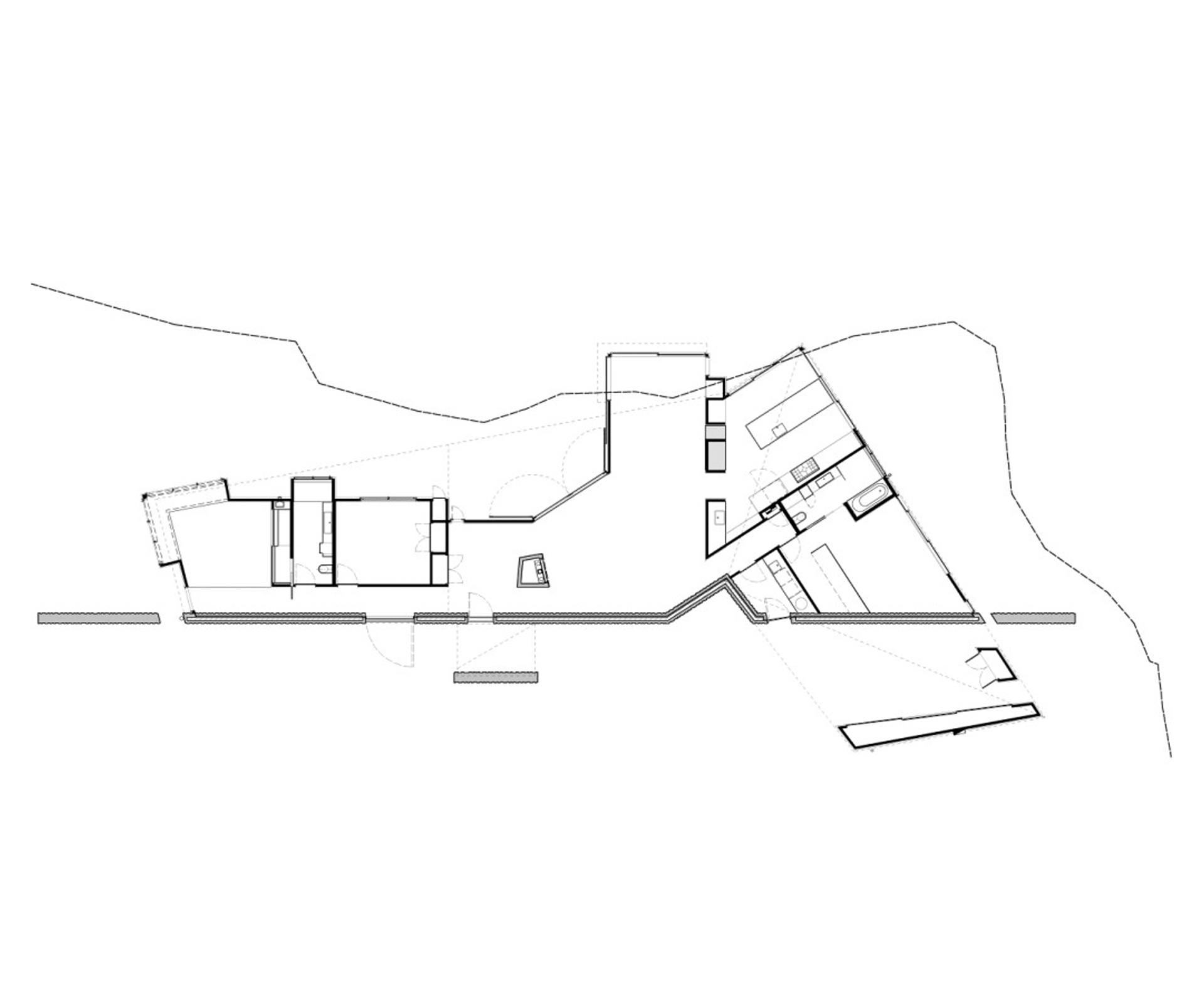

First, Shacklock had to get the site organised. Tight height controls meant she suggested that a metre of soil be scraped off the site so that the home’s main volume could rise to a peak of five metres. Flattening the site this way also allowed for the creation of a lawn around the house and an eastern courtyard adjacent to the kitchen and main bedroom bordered with Waiheke stone and a gnarled pohutukawa. Next, a series of 14 metre-deep holes were drilled and filled to stabilise the site.

The McKibbins knew that Waiheke Island’s cold southwesterly winds would roar over the valley towards the site, so Shacklock created a hefty, textured concrete wall that is visible on the exterior and interior of the home’s entire southern face. Over this she folded an intricate cedar ceiling, expertly constructed by builder Kevin Glamuzina. “I wanted it to not just be about the view, but about the feeling of being in the house,” Shacklock says.

But the views still demanded to be addressed. Shacklock collaborated with her colleague Paul Clarke and together they decided there were two main segments to the 180-degree vista from the house: two-thirds of the view, looking north and out to sea, showed no sign of human habitation at all. It was possible to see homes in the view to the east, but Shacklock loved how this view also took in glimpses of the rocky black cliffs and a nearby beach.

The plan they eventually developed utilises these outlooks separately. The big view north is the focus of the dining and living space, while the view east is the focus of the kitchen area, where big doors capture the morning sun and glimpses of the rocks nearby.

The balance between protection and precariousness is deftly handled. The living area has a fireplace and a big sofa backing onto that southerly concrete wall, and looks onto a terrace and the lawn leading to the cliff edge. The dining space, meanwhile, cantilevers boldly over the cliff edge. A glimpse downwards from there or from the kitchen’s full-length doors to the waves crashing on the rocks below is precipitous enough to easily induce vertigo.

This isn’t a huge house but is nonetheless full of diverse spaces. “You get different aspects from each room, and it’s always changing,” Sally says. “There’s not one area where I think we should have done something else.” A long wall of dark cabinetry provides a loose division between what Shacklock calls the “public” areas of the home and “the domestic and public realms”: the kitchen and, behind it, the main bedroom and en suite, where the ceiling dips low to create snug, enveloping spaces backed by that formidable concrete wall.

[quote title=”You get different aspects from each room” green=”true” text=”and it’s always changing” marks=”true”]

At the other end of the home is a guest bedroom and a multi-purpose space that serves as a screening room, study and extra guest room if needed. Here, at the terminus of the journey through the house, is another spot of repose, a deep window seat with a view across the lawn towards a border of century- old totara fenceposts and the sea beyond. It’s a place that feels well-held and secure, a comfortable contrast to the adventurous cantilevering at the other end of the house, and a demonstration of the architect’s skill at balancing these opposing elements.

[related_articles post1=”45478″ post2=”1367″]

Q&A with architect Wendy Shacklock

HOME You started this project early by looking for sites with your clients, didn’t you?

Wendy Shacklock I got to know Sally and Brian as we shopped together for a site. We were lucky enough for this perfect location to come onto the market, a smallish flat area running east-west atop a 40-metre cliff. Facing north are unimpeded views out to sea and across other bays. The brief was for a nest, Te Kohanga, and all that implies for home and security, but also hints at the precarious nature of where they’ve chosen to build. It is their permanent home.

HOME How did you go about responding to such a brief?

Wendy Shacklock It’s such a beautiful site, they really wanted something of good quality there. I invited my colleague Paul Clarke to work with me, and we were attracted to slightly different aspects of the site which have both been incorporated into the plan. The drivers became framing two separate outlooks – the intimate bays and the open sea – and the long, outstretched arms of the concrete wall, which is the grounding element for the nest and provides shelter from the vicious southerly aspect. I wanted the house to have a depth and presence that was not dependent on the view but enhanced by it. The house reveals itself gradually, offering little surprises along the way.

HOME Tell us about the work you did to the site in addition to stabilising the cliff.

Wendy Shacklock I wanted the volumes to rise up to the core of the house, where its ridge was to be five metres high, and to achieve this with the strict height limitation the top metre of the ridge was removed, which also lessened the steep approach from the south and gave us slightly more flat land.

HOME You’ve talked about the home’s solidity. What’s the most precarious part of the house?

Wendy Shacklock The dining box cantilevers out to engage directly with the cliff; you can perch and see over the edge of the nest straight down to the waves breaking over the rocks.

Words by: Jeremy Hansen. Photos by: Samuel Hartnett.

[related_articles post1=”667″ post2=”29327″]