During a visit to Waiheke a decade or so ago, an architect was struck by a simple, refined sculpture and the way that its ad hoc form, created from a roll of corrugated iron, twisted down a hillside, creating and enclosing spaces.

That intrigue ignited a creative exploration that resulted in a similar twisting form; this time, though, the form enclosed a series of indoor and outdoor spaces across multiple levels on a steep, central Auckland site. On either side of the folding form, cedar-clad volumes anchor the building, sentinel-like standing watch and containing the more intimate and inwardly focused rooms.

The south-facing site is at the rear of a relatively recent four-lot subdivision in Saint Heliers — a section many would see as too challenging. For Wayne and Lyn Frazerhurst, the opposite was true, and, with the help of their architect son, Mark Frazerhurst, the steep, overgrown site was transformed over the course of 10 years and a home evolved that they plan to live in for the rest of their lives.

A site of this nature, requiring numerous levels stacked on top of each other, is not often the obvious first choice for a retired couple.

“You could look at it in two ways: one, that it wasn’t practical with all the stairs needed; or, two, that the stairs would be a way to keep fit and mobile. We chose the second, and it’s paid off,” Mark tells us.

Stairs there definitely are — 49 internal steps. The house is spread over four levels, a garage on the lowest; above it the bedroom and en suite, and pedestrian entrance. Above that is a split level, housing the living/media room on the lower level with the kitchen and dining area half a level up. The crow’s nest houses a study.

This project, which began in 2012 and was completed in 2022, faced other challenges. There was a finite construction budget, which meant that the goal from the beginning was to get the building to a certain point and complete it with the help of family over an extended period, a process that required time.

By 2016, the house was at a point at which Wayne and Lyn could move in. It was essentially enclosed but very much unfinished. So continued the decade-long labour of love.

“For us, architecture is about the process. The process is as enjoyable as the finished result, and this project was very, very rewarding in that way. It was unforgettable going through this with my parents. It strengthened our already close family bond — I couldn’t have hoped for better,” Mark says.

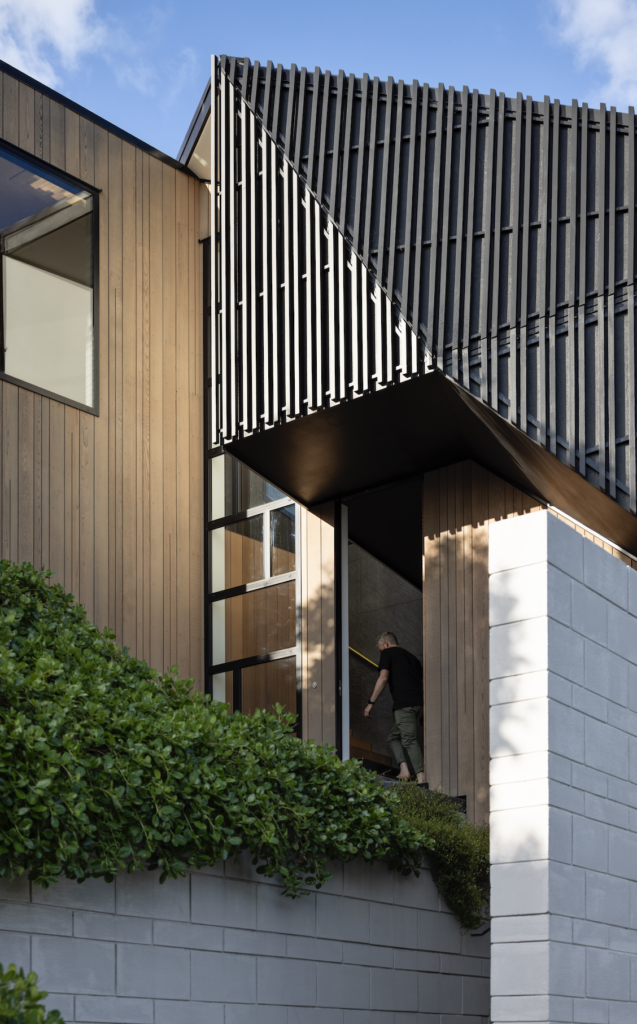

From the moment this house comes into view, it’s clear that this is a special place. The twisting black form zig-zags down the hill, creating a series of angles that converge and fall away, offering a captivating sense of movement and depth.

At ground level, there’s intrigue about the building’s form. The first interaction with it is introduced with masonry walls that surround the garage and enclose the pedestrian entrance, which is reached via a set of stairs to the west.

The garage door, a nod to Wayne’s aeronautical career, slides away in the manner of an aircraft hangar door. Clad in Abodo battens over a polycarbonate sheet, the door allows light to perforate the gaps and filter into the otherwise-shaded basement area.

A curving concrete stair leads to the entrance on level one, at which there is no immediately obvious door. Ship-lap cedar is broken by vertical windows that mimic the offset pattern of the blocks in the masonry walls below. The only indication of the door itself is a custom black pull handle that Mark handcrafted for the house.

“The entrance was designed to feel quite subterranean,” Mark explains. The dark tiling of the floor continues up the wall, and the ceiling is painted black.

“You look up through a double-height void where it’s lighter, so you have a sense of the house pulling you up to the light,” he explains.

Here, three levels overlap, allowing for the installation of a lift should the need ever arise. It’s the connections in this house that offer something really special — between spaces, materials, textures, and light.

When Mark first started modelling for the house, it was the view shafts that were of critical focus. It was 2012 and he didn’t have a drone, so he used the next best thing: a camera on a stick. It was a move that paid off; the light and views here are immersive — and carefully framed.

From the kitchen, through a slatted screen and glazing to the western side of the lounge, you can see as far as One Tree Hill in winter when the trees are bare. To the south, a panoramic kitchen window frames ‘green sea’ views of the southern crater wall of Glover Park and the iconic water tower above it.

The same view is visible from the outdoor seating area, which extends out from the kitchen to the north, thanks to the low placement of the window.

It’s a seamless transition from indoors to out, with the same tiling continuing outside across a flush, blurred threshold. Behind, a retaining wall steps down — a move that allowed for its volume to be broken and one that references the manner in which Italian quarries are terraced for vehicular access.

“When they’re no longer in use, those quarries get taken over by greenery, which is the idea here with planting growing up and trailing down the terraces,” Mark explains.

In a corner, there’s a moment of playfulness in the form of a deck of sorts. It’s not flat, and it’s not underfoot, but it does introduce timber decking boards. Rising up into a corner to the east, it’s a little triangular moment that provides the perfect place to sit. Angular and sloping, it echoes the folds and resulting triangles of the external form.

The kitchen and dining area was intentionally designed to take up a significant proportion of the house. It, like every space in this dwelling, is a beautiful meeting of angles and fractured light. Overhead, a cedar-clad hanging rangehood offers an abstracted, inverted interpretation of the cedar sentinels that form buttresses of sorts on either side of the house, while irregular angles in the benchtop and island further solidify the geometric playfulness of this space, the “underside of the folds”.

In the adjacent room — an adaptable space used as an art room for Lyn, a mezzanine guest bedroom, a scullery, and a laundry — the playfulness of its neighbour is not lost. Here, in a very confined footprint, Mark took cues from the concept of sleeping above the cabin of a camper-van, and designed and made a mezzanine sleeping loft — accessed via portable ladder — that allows for guests to stay comfortably in this otherwise one-bedroom home. Beneath the mezzanine is ample desk space and storage.

While the material palette as a whole is quite simple and defined primarily by the tiles and cedar inside, there are pops of colour. The stair handrail is painted in Resene Bright Spark, a joyfully bright yellow; outside, the same colour is used for two deep window frames, offering a striking contrast to the black and cedar.

“I think sometimes black houses can become a bit too serious. Dad likes yellow and it’s a happy colour, so we used it to bring things back into the realm of fun.”

Everything about this house is considered and has a story. From the production line the family created to fabricate and install the rain-screen sections, to the construction of the folded ceiling trusses, to installing wall and ceiling linings, and the construction of bespoke cabinetry, each detail was a labour of love completed by a family committed to creating something special — and they’ve definitely done that.