In 1968, Claude Megson devised a house of angles, drama and intrigue for the artist Roy Good in Oratia. The gallery-like walls are now adorned with his art

This dramatically angled house was designed to display the owner’s art

This year Roy Good celebrates 50 years as a practising artist and designer. Retrospective exhibitions open in December at Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery in Auckland, and in 2019 at CoCA, Christchurch. At the latter, Parallel Universe by art historian Edward Hanfling will be launched – a book covering 50 years of Good’s twin careers in art and design. Also celebrating its 50th anniversary is the Claude Megson-designed house that Roy and his wife Sue built in Oratia, west Auckland.

The ‘Good House’ is a key work in Megson’s oeuvre. Roy and Sue Good were a young couple when they commissioned Megson, himself only just into his 30s. “Sue’s parents owned the section and I fell in love with the location,” says Roy. They gave the architect a free hand – “a house for an artist and his future family – apart from that it was very much a blank sheet. There were many meetings and sketches before we could view plans that promised an exciting result. I think it was the sculptural appearance of the elevations that I liked and the general avant-garde look of it.”

Roy had attended Ilam Art School in Christchurch and relocated to Auckland in the mid-60s. He soon became the friend and colleague of several local artists, including Milan Mrkusich, forming a tight-knit group of fellow abstractionists. Roy was one of a number of Megson’s clients who moved in this artistic community.

In 1968, Megson had just completed three townhouses in Hapua Street, Remuera, for Milan and his wife Florence. They were set just below their own house, which Mrkusich designed in 1951-52 while part of Brenner Associates. Later, in 1974, Megson created two townhouses for Gavin Rees on the same street. Rees bought Roy’s work and had a pioneering interior design shop importing modern furniture (as had Brenners before him).

There were other clients who played a significant role in the arts. Megson designed a house in Darwin Lane, Orakei Basin, for Bill Cocker, an avid collector of paintings by Ralph Hotere and Richard Killeen. In the 70s, Cocker and his sister Finola acted as developer for one of Megson’s most enduring works, the ‘Cocker Townhouses’ in Freemans Bay.

Given these many personal and professional connections, it’s little surprise that Roy and Claude quickly discovered their mutual empathy for European art, especially De Stijl, Piet Mondrian and Gerrit Rietveld. “Claude used to talk about Theo van Doesburg and Mies van der Rohe,” says Roy, who was impressed with Megson’s interior perspective drawings and thought they looked “similar to van Doesburg’s own perspectives”.

In the ‘Good House’, Megson’s white planes overlap in rapid succession, creating foreshortened perspectives through the house and jump cuts between spaces. The spectacular ceilings, lined with heart-rimu rafters and sarking, rise and fall above these planes. An inverted pyramid, all raw material and weight, is suspended over the snug roof. It assumes a more conventional gable form above the living space, only to descend over the dining space, then rise back sharply with the main stair. Daylight brings this movement together and affords moments of poise. A low, square window looks back to the driveway. Above it, a sliver of light glances down the wall from a source higher up.

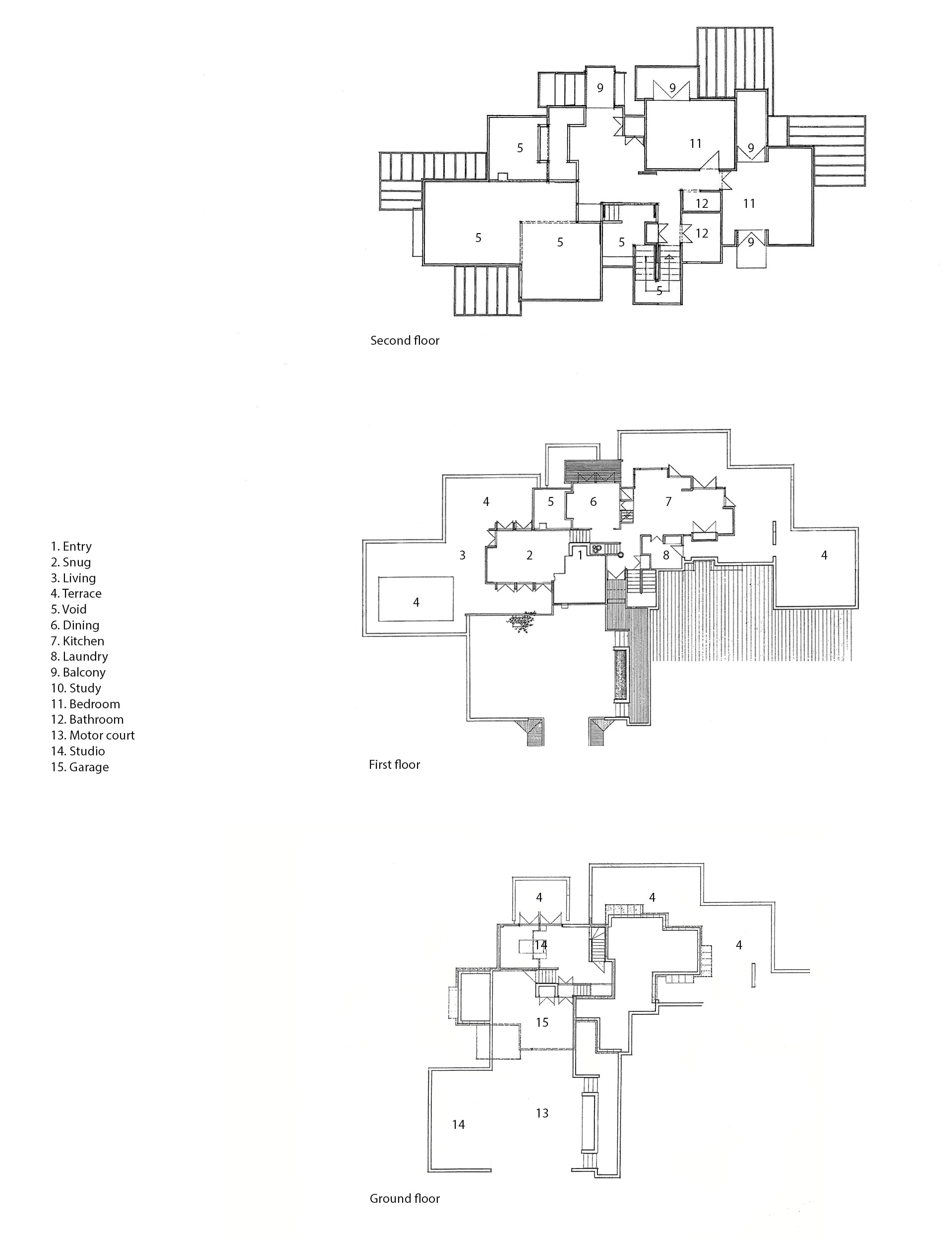

The front door is approached from an external gallery that brings you into the middle of the plan. The living spaces are ahead and up a short flight to the left. The kitchen and breakfast area is off to the right. Stairs to your right lead to bedrooms on the top floor. A stair to the immediate left leads down to a double garage, then down again to the studio. Another stair straight ahead also leads down to the studio.

This short account, which introduces some of the house’s intricacy, still fails to describe the interior as experienced. The layout is made more complex again by split levels, balconies, voids and an absence of anything approaching a straightforward corridor. Even though Megson created numerous long vistas between rooms, they never quite extend to the limits of the building and the house’s actual size is never fully appreciable from any one standpoint.

Over the years there have been some inevitable modifications to the house. The family grew, the dining area was enlarged, a few internal walls were added and the kitchen was remodelled about 20 years ago. These alterations pass almost unnoticed. Today the interior feels both original and contemporary and is in as good a condition as ever.

The bigger changes were those forced on the owners. A cantilevered floor above the dining area had to be reinforced after sagging from use – Megson always being one to push the structural envelope. The roofs – typical of a Megson house – all drained into tiny gullies and gargoyles. His aversion to conventional roof detailing was a perennial failing and one that was quickly exposed by intense Waitakere rainfall. The Brownbuilt metal roofing you see today is original but flashings and gutters are new and came at considerable cost to the Goods.

It is perhaps ironic that although the brief was to design ‘a house for an artist’, Megson’s open plan provided little regular wall space for displaying art. Far from proving an obstacle, the architecture forced Roy to come up with a ‘salon-style’ hang, with works mounted high and wide. The collection constantly evolves and includes kindred New Zealand artists Logan Brewer, Guy Ngan, Don Peebles, Theo Schoon, Marté Szirmay, Geoff Thornley, Geoff Tune, Gordon Walters and Meryvn Williams, as well as prints by some of Roy’s international influences Yaacov Agam, Josef Albers and Victor Vasarely.

These works interact visually and across time with Roy’s art, which is on show throughout the house. Pieces such as ‘Rhombus Suite No.2’, positioned above the living-room bookcase, appears purpose-made for the wall. His work has long been noted for its play with perception. Crisp blocks of colour interlock with shaped canvases, flickering between 2D and 3D and shifting the eye between centre and border. Roy’s paintings are often framed with precisely made aluminium flat plates, echoing Megson’s white walls, which themselves are delineated by painted hardboard edged with dark timber.

What enriches this house most is that it’s not just the marriage of two visions – Claude Megson’s and Roy’s, but a third – Sue’s. An assistant to plantsman Hugh Redgrove, who lived nearby and authored A New Zealand Handbook of Bulbs & Perennials (Godwit, 1991), Sue has developed the garden over the years.

[gallery_link num_photos=”14″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/claudemegson-oct9.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/architect-artist-design-home” title=”See more of the home here”]

“It was set in process by the footprint of the house and its retaining walls that expand into the site and bush,” says Sue. “One thing that Claude did really well was placement on the site, making the most of the hill profile and views. Excavating into the hill for the lower ground level with the other spaces stacked above into three levels created a castle-like feel to the building that another obvious siting of the house on one level would not have achieved.”

The building’s concrete-block retaining walls form a semi-enclosed courtyard on arrival, preventing any sense of outlook or release. Cedar board-and-batten volumes bustle and jog, spanning across the top of these walls. To the right and above head height you climb up to a somewhat formal first introduction to the garden as a whole. From here the home’s true scale is masked and it has the appearance of a cottage sitting on a lawn, surrounded with box hedges. Only once you’ve gone deep into the house is the valley beyond revealed and you appreciate that the land falls dramatically away to the north-east.

Numerous decks and balconies project from the building, providing views to the Waitematā Harbour, with downtown Auckland in the far distance. Two small, square courtyards extend left of the living room and right of the kitchen, offering retreat or acting as sun traps at different times of the day. Paths lead away from these, taking you down and around the lower slopes, leading you through Sue’s cultivation of natives (kānuka, mamaku, nikau, ponga and renga renga lilies) and exotics (azaleas, bromeliads, camellias, hellebores, hydrangeas and vireya rhododendrons).

In late winter, maples blaze forth reds, oranges and pinks. When the place is alive with colour, the deep connection between Sue’s ideas of landscape and Roy’s of art and design are inescapable. The house, its owners and their architect are in a sense each something of an exotic in the bush.

Words by: Giles Reid. Photography by: Jackie Meiring.

[related_articles post1=”83631″ post2=”83600″]