A compact house in the Karekare bush by Stevens Lawson is designed around contemplation and retreat for a designer and his family

This bach in the Karekare bush is the perfect place to ‘switch-off’

“I’m an obsessive worker,” says Dean Poole, a founder and director at design studio Alt Group. “It’s not like a job – we achieve a lot because we like working. But this is a total escape. As soon as you hit the hill, you can’t check your email.”

At the bach that Poole and his wife Krista Dudson built at Karekare a couple of years ago, there’s no wifi or cell reception. And there’s no art: just a lovely collection of objects the couple knew would go in the house before they even had a design. “We originally thought we’d put loads of art out here,” says Dudson, but they’ve come to appreciate the stillness of the place after the visual and digital overload of their Auckland lives.

The west-Auckland valley has attracted intellectuals and artistic types since sections were first opened up in the 1950s. The Dudson-Pooles have a long history at Karekare – Dudson’s sister has a house across the road – and they’ve been coming here for years. In 2010, the couple bought a steep sliver of bush a short walk from the beach, with a narrow ledge pinched out of the hill occupied by a couple of illegal shacks.

Stevens Lawson’s initial response was much more complex than the house you see on these pages. Two storeys climbed the hill in an arrow shape, the upper storey overhanging the other and clad in Corten steel. It would have been dramatic, but came in much too expensive. And besides, the couple felt strongly that the house should have, as Poole puts it, “a humility”.

Stevens Lawson went back to the drawing board, pulling the house in to be smaller and simpler – a two-storey timber box with cross-laminated timber beams doubling as floor and ceiling between. It’s clad in black corrugated steel, an economic, hard-wearing material that sits nicely in the bush. “It’s a simple shed with an interesting front,” says Nick Stevens. “It’s a bit of a whare, with a nod to the colonial hut, a basic hut in the bush – but when you get inside it’s more refined.”

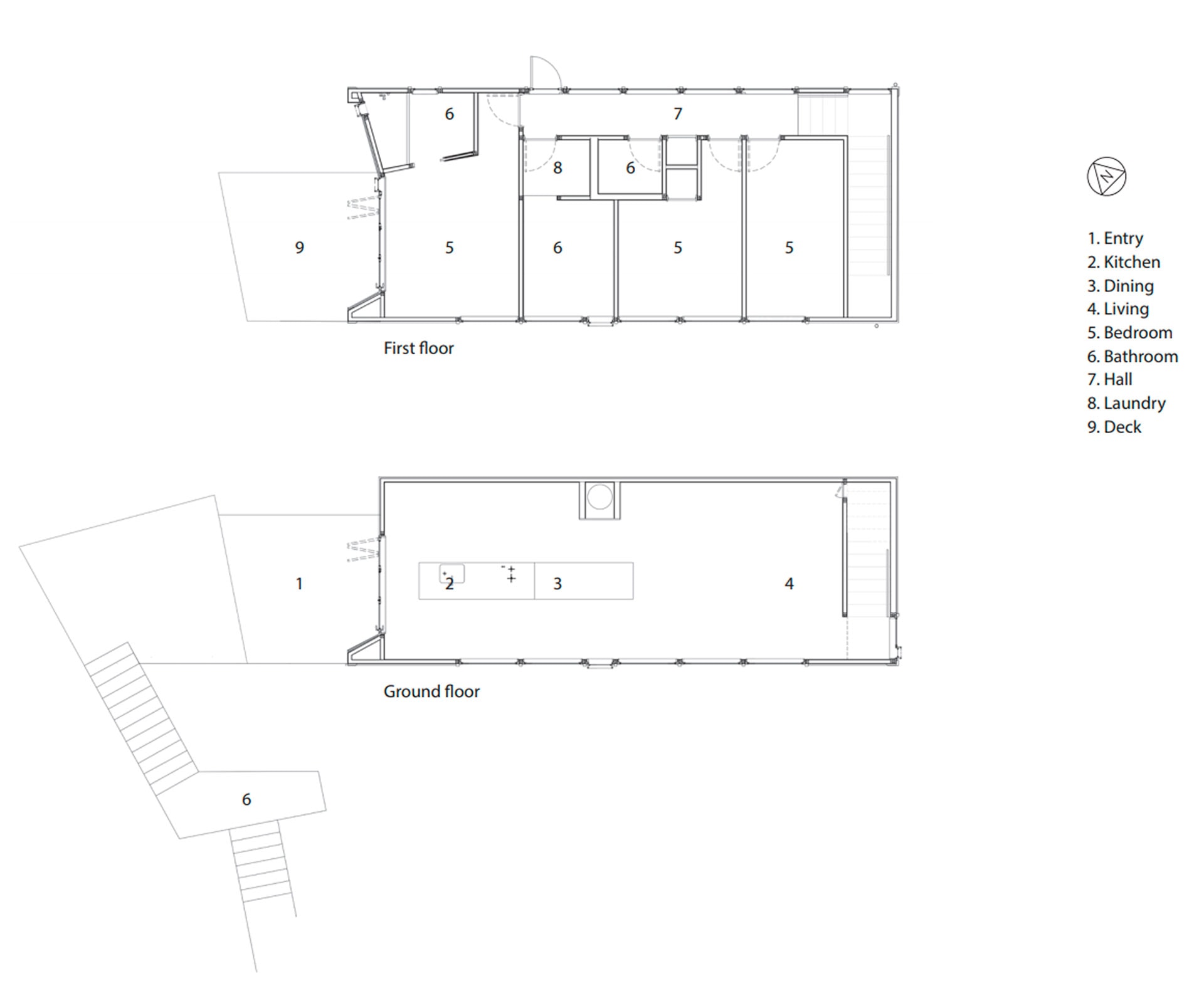

Downstairs, a long narrow living room with a line of floor-to-ceiling windows overlooks the bush; upstairs are bedrooms and two bathrooms off a corridor. There’s exactly as much space as they need, and the rooms are loose, even unfitted, with prized furniture in place of custom cabinetry or fittings.

The house is approached up a short driveway – which the day I visited had been washed out in a storm, flooding their family’s place across the road – with parking in front of a massive black-stained retaining wall. From here, timber steps zigzag up the slope and the house reveals itself slowly through the nikau, an asymmetric gable that frames the top level. From here, a deck juts off and covers the outdoor living area below, which is screened with elegant black steel slats. You then step straight into the living room, which is dressed in a pure palette of wood – birch ply on the walls; oak floors and cabinetry.

Outside, nikau stand in the bush, some stretching above the roof. The view is telescoped out to the north and the sunny valley. It’s a move that’s surprisingly inward looking for those used to beach houses built around even a peep of view. That’s deliberate. “I think on the west coast it’s really important you have a sense of interiority,” says Stevens. “You really want a room and a fireplace.”

It might have humility and it might have its roots in a long line of vernacular buildings, but the execution here is precise. Joins between the ply line up with laser-like precision throughout the home. Standard pre-primed jambs arrived with the aluminium joinery, but the couple decided to remove the windows and install custom plywood jambs that integrate seamlessly with the walls.

The doors upstairs are made from two pieces of high-pressure black laminate within a steel frame so they don’t warp. When closed, they sit as black cutouts in the line of birch. The kitchen took a year to conceptualise and install, during which time the family made do with a laundry sink and a couple of camping burners. Poole designed the kitchen – which the architects drew up following a detailed brief – to evoke a workroom aesthetic; the style of the bench resembling a builder’s work horse.

[gallery_link num_photos=”11″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Karekare3.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/hillside-home-makes-case-for-plywood-walls” title=”See more of the home here”]

Poole trained as a sculptor and spent many years in a workshop, which informed his concept and cabinetry that looks and functions as beautiful objects. Three monolithic oak-wrapped towers house different functions – fridge, pantry and oven, plus storage. The idea of ‘kitchen as furniture’ might be de rigeur, but this is less kitchen, more a loose assemblage of forms that sit beautifully as pieces of sculpture. “Everything has a use,” says Stevens, “and all the parts are independent from each other, forming an eclectic array of components. There’s something really nice about the character of a collection of parts.”

The house is formed around specific pieces of furniture. In the brief, the Dudson-Pooles named what they would bring into the space, including the ‘Vieques’ bathroom fittings by Patricia Urquiola for Agape . They play on traditional steel forms, rustic yet polished, each piece stripping function to its singular use, with no extraneous detail. Much like the house.

“It’s not overdone and that’s important,” says Poole. “It’s truth to materials. You’re not puttying the holes: you can see how this went up, it was cut and it was nailed. It’s got to look like a human did it,” he pauses. “It’s a bit of Kiwi-sabi, you know what I mean?”

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Mark Smith.

[related_articles post1=”83564″ post2=”82630″]