A restricted material palette, a modernist soul that is part Californian, and a touch of Japanese — all combine to form an entirely picture-perfect Waiheke home by Rowe Baetens Architecture.

HIGH ON THE hills near Onetangi on Waiheke Island, two artists purchased a property with the aspirations of building a home with an adjacent structure that doubles as a temporary rental and an arts studio.

The couple had become fascinated with Tom Rowe’s Volcano House in Devonport, an impressive, award-winning suburban house wrapped in volcanic basalt, significant amounts of steel, and tōtara, all stitched into an elegant pavilion. That award-winning house, with its echoes to United States East Coast architecture, connected the home to its surrounding landscape impeccably.

“The previous owner [of this Waiheke site] had planted this incredible garden,” explains Rowe, “and the clients had been looking for a broad north-facing expansive site. At the initial meeting, we stood on the roof of the old house to get a picture of the view and potential vista.”

The site sits near the crest of a hill, so Rowe’s solution was to dig into the hill so that the topography could provide shelter to the house as well as make the structure connect with the landscape. This also provided a modicum of separation from the nearby suburban fabric, making the house feel almost rural in its garden-clad isolation.

“You wouldn’t know that you’re right on the edge of suburbia,” Rowe says. Pointing out an established landscape, he adds, “An existing ’50s bach sat within a wild tropical garden that the clients wanted to keep. There was a balance to be achieved between making sure we didn’t lose any plants and removing the existing house that was very tired.”

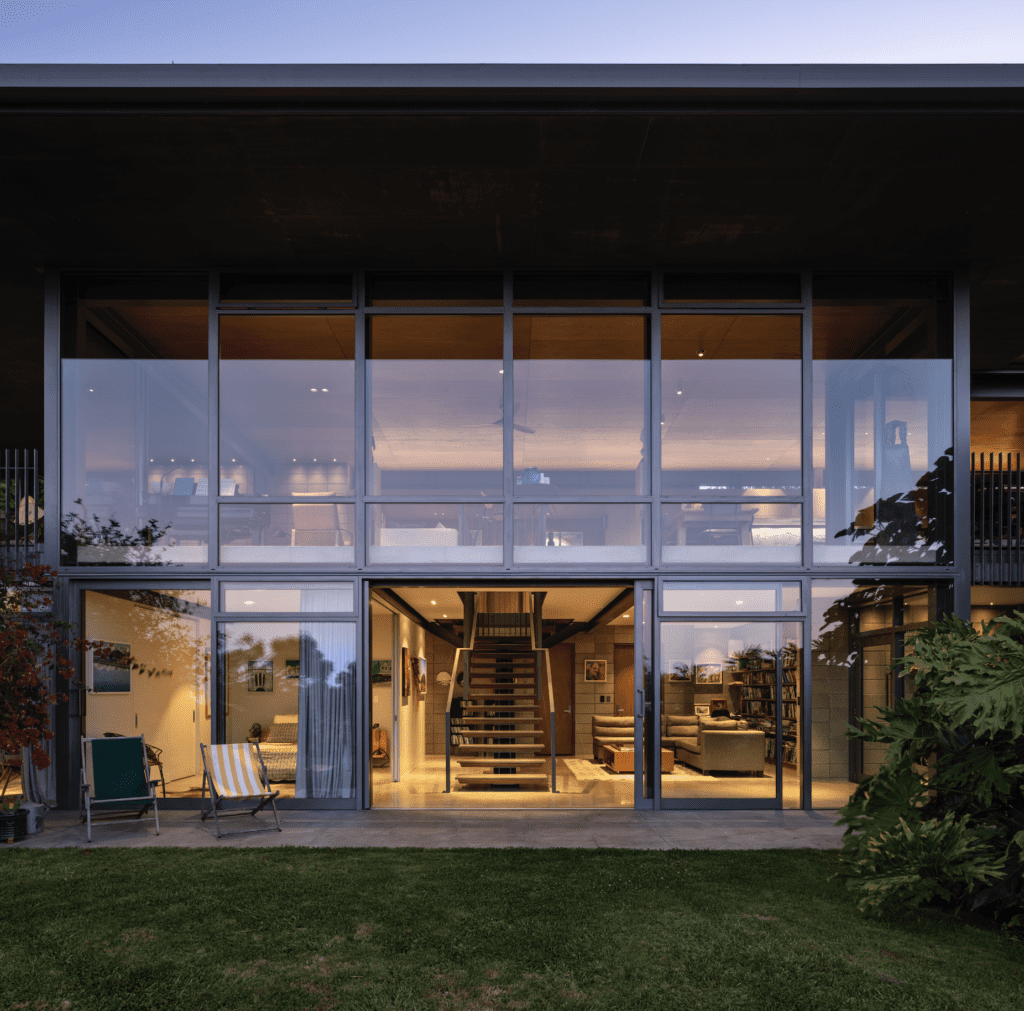

The new house has been carved into the landscape. Rowe’s desire to keep the structure stealthy called for horizontality and transparency, a lightness of stacking, and a restrained palette of materials expressed with linearity and rhythm.

“It is very constructivist,” says Rowe, alluding to the style of the structural expression that sought functionality rather than symbolism or abstraction and was known for its restrained use of robust materials. “The exterior is essentially glass with stack bond concrete block, so you get this linear module type of pattern, and the interiors of the structure and everything else began to mimic that. There’s a logical module, a logical kind of rhythm within the house.”

There is a refined level of architectural simplicity here. Two storeys of glass, steel, and concrete block, carefully set between a hill and the vast views of the ocean. That level of transparency has meant the interior has been kept linear and uncluttered, with the few aesthetic moves — such as stairs, inbuilt furniture, kitchen, and hearth — enjoying a Donald Judd–like simplicity of geometry and materiality.

“We designed a cantilevered hearth for the fireplace to sit on; normally you would use stone, but we just used concrete capping blocks,” Rowe says, pointing out the restricted number of materials throughout the house. “Everything, and every element becomes a language of repetition, which is kind of fun, and totally obsessive!”

Yet, it is not purely about reductivism; the house does have a few of what the architect calls, ‘Look, no hands!’ moments.

The immediately obvious one is an impressive cantilever on the western elevation that creates a small living room — with delightful inbuilt seating — within the canopy and, below, the void that allows cars to manoeuvre in and out of the lower-floor garaging.

Entry to the house is under this cantilever. To reach the social area, you go up a set of beautifully articulated stairs.

“They have floating treads and, again, in the spirit of minimalist materials, they are made up of sheets of ply and plywood box beams that you can buy off the shelf.”

On the north side, the roof extends outwards into a generous two-and-a-half metre overhang to provide shelter outside — creating an al fresco, shaded area — and sun protection for the most exposed part of the interior.

The hipped roof was chosen both to allow the building to be more discreet in the land and because its linearity creates a more soothing interior.

“The horizontal ceiling and roof lines are very different to live in [in comparison to] something pitched,” Rowe tells us. “A pitched ceiling has a direction that is either pulling you one way or pushing you the other way, whereas a flat ceiling is calm.”

Adding to the soothing intent of the ceiling is the fact that the walls don’t meet it; at their junction is a thin strip of clerestory windows that make it seem as if the ceiling is floating above the internal volume.

“It becomes a ribbon of light that runs around the interior; the roof is detached and light, which is something we strive for in our work,” says Rowe.

Just as the circulation and social spaces are all arranged around the impressive glazed wall, the more private areas have been nestled into the hillside, where a type of cuboid concrete block form reads as a strong shelter, cocooned from the light-filled, openness elsewhere.

Although my initial comparison is to Ron Sang’s Brake House — with its bushy surrounds and glassclad cantilever within a rectilinear, modernist form — Rowe seems more comfortable talking about Tom Kundig, with his great expanses of glazing and nearly mathematical rhythms of steel.

There is, as well, in this structure, a peculiar Californian modernism, mixed with a touch of serene Japanese calm — in an entirely beautiful Waiheke rhythm.