Two of New Zealand’s brightest architectural brains undertook the tough task of choosing our country’s best homes from the past 80 years

Brown bread and sugar cube: a story told two ways

To celebrate HOME magazine’s 80th birthday, we summoned two of the country’s biggest architectural brains to choose the best New Zealand homes of the past eight decades. Julia Gatley is the Head of School and Andrew Barrie is Professor of Design at the School of Architecture at the University of Auckland (both also contribute regularly to HOME). They weren’t jubilant about the idea of compiling this list, as these sorts of exercises are always contentious. “It’s bound to cost us friends,” says Barrie, grimly. “Every person’s list would be different.”

Rather than choose a single home for each decade, they decided to highlight two important strands in this country’s architectural history. This magazine’s first editor, Victor Beckett, expressed hope that the modernist movement sweeping the world in the 1920s and 1930s would allow many more people to live in superior homes. Some New Zealand architects enthusiastically adopted what was called the International Style, designing sleek, flat-roofed boxes with open-plan interiors. The white squareness of these buildings led Gatley and Barrie (and other historians) to liken them to sugar cubes.

[quote title=”Every person’s list” green=”true” text=”would be different” marks=”true”]

Another group of architects took a different path, adapting modernist thinking to local contexts in an attempt to create a distinctive New Zealand architectural identity. Because these buildings were often dark-stained or creosoted, and because their architects’ intentions were often earnest and wholesome, this is the “brown bread” strand of the country’s architectural history.

These categories are never pure or uncomplicated, but it is possible to see these two strands of architectural approach running parallel through the decades. To this end, Gatley and Barrie have chosen one “brown bread” house and one “sugar cube” house for each decade from the 1930s to the noughties. Their most recent selections deliberately show how these distinctions increasingly blur.

These choices are not without qualifiers. Asked what was the most painful exclusion for him on the list, Barrie replied “pretty much all of them”. For her part, Gatley says the selection doesn’t accurately reflect the way architectural leadership was dispersed regionally. Auckland was the scene of exciting buildings of the brown-bread variety through the efforts of Group Architects in the 1950s, for example. In the 1960s, the robust concrete-block creations of Warren & Mahoney and Peter Beaven shifted the spotlight to Christchurch before the entrancing Wellington creations of Roger Walker and Ian Athfield grabbed national attention in the 1970s. “We haven’t been able to tell that particular story within our list and it’s Warren & Mahoney and Peter Beaven that have dropped out,” Gatley says. “Part of the reason for that is that both of them did a lot of their best work within the public realm rather than having a singular house. They did many good houses, of course, but their other works were more definitive.”

Here, then, are our experts’ selections. We encourage you to debate their merits at length.

BB – brown bread

SC – sugar cube

1930s

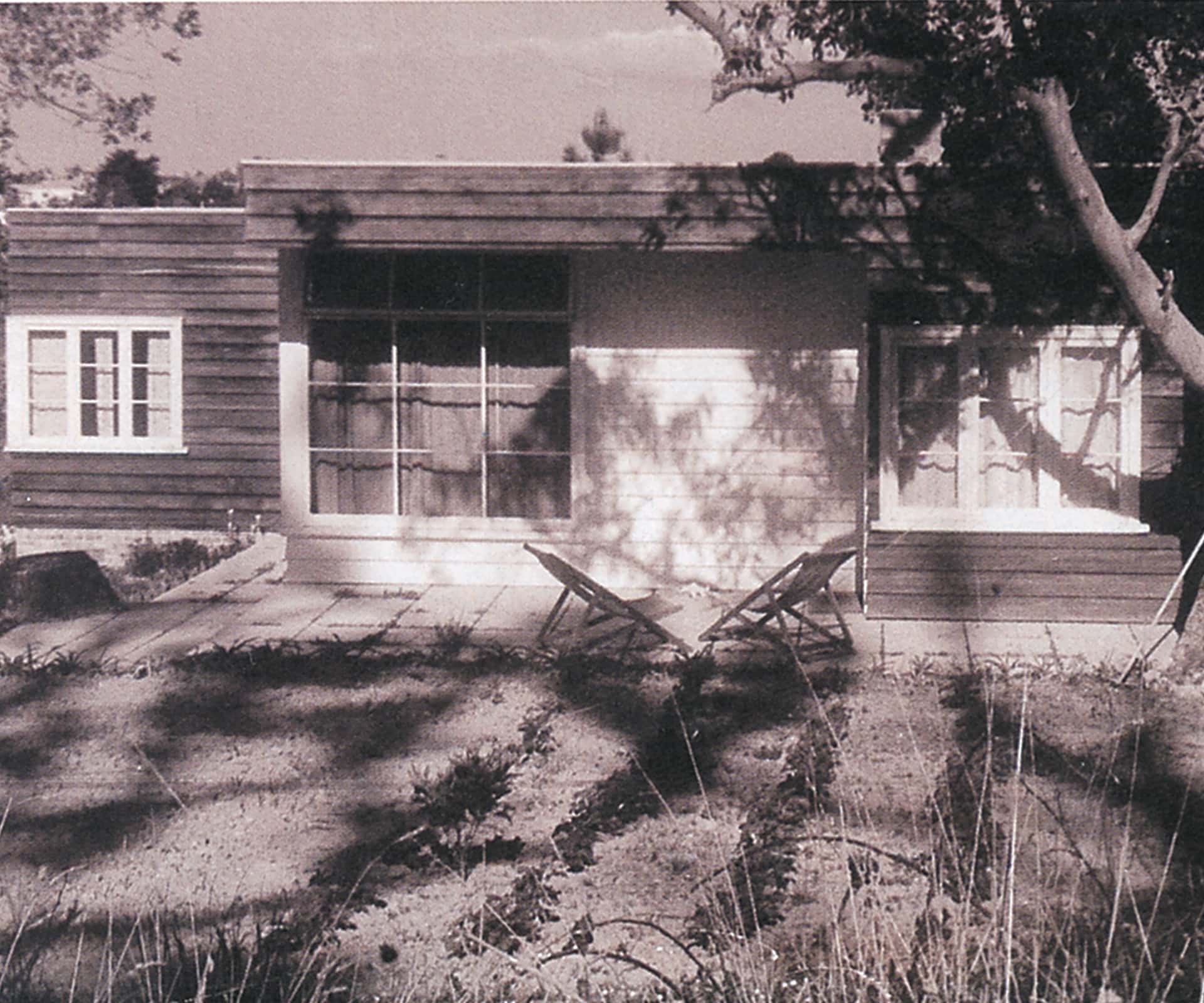

Architect’s Own House by Vernon Brown, Remuera, Auckland 1939

“Vernon Brown was English and he studied architecture in London,” Gatley says, “but in Auckland his circle included the nationalist writers Rex Fairburn and Frank Sargeson. Brown became interested in ideas about the expression of New Zealand-ness and searched for built forms that were different from the clean white surfaces, flat roofs and large amounts of glass of international modernism that had developed in 1920s Europe.” The architect designed conservative Georgian cottage-type houses in the 30s, but right at the end of that decade he started to develop his own language of timber houses with walls that were either creosoted or stained very dark brown. “They were textured and dark and perhaps evoked the New Zealand bush in that respect,” Gatley says. (We admit to cheating a little here: Brown designed his first home for himself in 1939, but because it was impossible to find an exterior shot of sufficient quality, we’ve chosen this image of a home nearby he designed for himself two years later. It still stands at the end of Victoria Avenue by the water, but has been heavily modified). BB

The Simpson House by Robin Simpson, Greenlane, Auckland 1938–1939

“Robin Simpson and Vernon Brown were in partnership for a time, so their work was quite closely related, but Simpson is best known for a house that he designed for himself in 1938,” Barrie says. “It’s a white cube with a big rectangular chunk carved out to form an outdoor living space, and with relatively open planning inside. It’s one of the very early New Zealand examples of our version of international modernism – although its construction is not very far from a typical New Zealand house, with a wooden frame and linings.” The home was purchased in the early 2000s by writer (and longtime HOME contributor) Douglas Lloyd Jenkins, who restored it and still lives there now. SC

1940s

The Haigh House by Vernon Brown, Remuera, Auckland 1942

Yes, it’s that Vernon Brown man again. “Using a house by Vernon Brown here is unavoidable,” Gatley says, “because he was really leading the charge to explore what New Zealand-ness in architecture might mean. Internally, his homes featured quite a lot of timber for linings, and they were also very efficiently laid out: nowadays some of them feel quite small, but he was very clever in his planning. The Haigh House is one of the bigger ones, distinguished by an angled wall in the hall and a bright red bathroom. It has a recessed porch, painted off-white, which became something of a Brown trademark. They became known for being like coconuts with a bite taken out of them,” Gatley says. Threatened with demolition, the Haigh House was moved to a site near Pahi on the Kaipara Harbour in 2002 and sensitively renovated. BB

The Donner House by Tibor Donner, Titirangi, Auckland 1946–1947

“Tibor Donner was a serious modernist,” Barrie says, “and the house he designed for himself has a lot of the key modernist elements, although it could be described as ‘tropical’ modernism in that it’s quite fruity, with curved walls and crazy paving, with strong textures and a spiral staircase leading up to the roof. Its open-plan living spaces face the sun and a flat lawn. It’s not rectilinear like a lot of European modernism, but has a looser style that perhaps feels a bit more Brazil than Titirangi.” The house is now owned by architect Paul Jenkin, who has been sensitively restoring it for almost 20 years. It is now a Category 1 Historic Place. Donner, who also designed the Parnell Baths and the Administration Building tower in Greys Ave, was chief architect of the Auckland City Council until his retirement in 1967. SC

1950s

Rotherham House by Bruce Rotherham, Devonport, Auckland 1951

There’s a personal connection to this selection: Julia Gatley lives in the Rotherham House with her partner Jeremy, Bruce Rotherham’s son. But she was a fan of the home long before she had the chance to own it. “The 50s in New Zealand architecture has a lot of great houses, and lots of people when they think of 1950s New Zealand houses think of Group Architects and the work they were doing in Auckland,” she says. “The Group were best known for the claim that New Zealand needed its own architecture that responded to local climate and local conditions. Bruce Rotherham was a member of the Group who designed and built this house for himself and his family. He was very conscious of what he called ‘space formed by building’ or ‘volume formed by materiality’, and giving expression to the building materials. We now enjoy the stone, the timber, the brick and the wall of glass that faces the bank on the south side.” Needless to say, this home is in particularly safe hands. BB

Sutch House by Ernst Plischke, Brooklyn, Wellington 1953–56

“This one’s actually a very difficult call,” Barrie says. “This is the era of the Case Study houses in California and all of those ideas were floating across the Pacific and being utilised by firms like Mark-Brown & Fairhead, Brenner Associates, Newman Smith and more – all of them doing beautiful, crisp, glassy pavilions. The Sutch House, however, is one of the most beautiful in New Zealand, helped of course by the fantastic site looking out over Wellington Harbour and the fact that it was designed by Plischke, an Austrian immigrant to New Zealand who was an architect of international importance.” The house was sensitively restored by architect Alistair Luke in the early 2000s for the daughter of Bill Sutch, the original owner. SC

1960s

Athfield House by Ian Athfield, Khandallah, Wellington 1965

“So Ian Athfield started designing and building his own place in 1965,” Gatley says, “and right from the outset it comes to represent something of the counter-culture of New Zealand architecture. He was prepared to make a statement to do something different on this very visible site on the hillside in Khandallah, so that if there were people out there who might be brave enough to want something unconventional in their house, they would see Ath’s place and would know who to go to for their own unconventional house.

That strategy worked for him: he was able to quickly establish himself doing these really interesting and unusual houses around the hills of Wellington. You can read 19th-century cottages into it, with this bunch of small, discrete spaces each sitting under their own roofs, which was quite different from the open planning of the Group and the other 50s modernists.” And yes, we know it’s white. “The brown bread/sugar cube distinction is more about a philosophy,” Gatley says. “This house represents the looser and more raw or hands-on side of things compared to the slickness of the International Style.” Athfield, of course, went on to become one of the country’s best-known architects. His wife Clare has remained there since his death last year, along with more than 20 others. The Athfield Architects offices are there, too. BB

Alington House by Bill Alington, Karori, Wellington 1962

Architect Bill Alington had a genuine and deep connection to international modernism that was partly formed when he completed a master’s degree at the University of Illinois. “Mies van der Rohe was teaching at the nearby Illinois Institute of Technology and Alington met him there,” Gatley says. “He was very influenced by Mies in the design of his own Wellington house, which has a kind of classical rigour in its planning.” Adds Barrie: “It’s very connected to what was happening in the United States at the time – you could go to the town of New Canaan where all the New York modernists were busily building beautiful houses, and the Alington House would sit as comfortably there in the trees of Connecticut as it would the New Zealand bush.” Alington designed the house for himself and his family and it’s had two very respectful owners since he sold it. SC

1970s

Britten House by Roger Walker, Karaka Bay, Wellington 1974

“The Britten House was designed for TV celebrity chef Des Britten and his wife Lorraine on an incredibly steep site which other architects weren’t willing to work on,” Gatley says. “Roger Walker was quite happy to accept the challenge. There are a lot of small spaces under their own roofs, and each space is a different floor level from one to the next. The surprising thing about it is the establishment of an outdoor living space as a kind of courtyard at one of those upper levels. Roger Walker was really having fun with this, and he and Ian Athfield were egging each other on to do the more anti-establishment and challenging kind of work in this period. Roger admired the Japanese Metabolist architecture of the 1960s, with its fixed cores for structure and services, including stairs, and the potential for change in the spaces radiating out from them.” BB

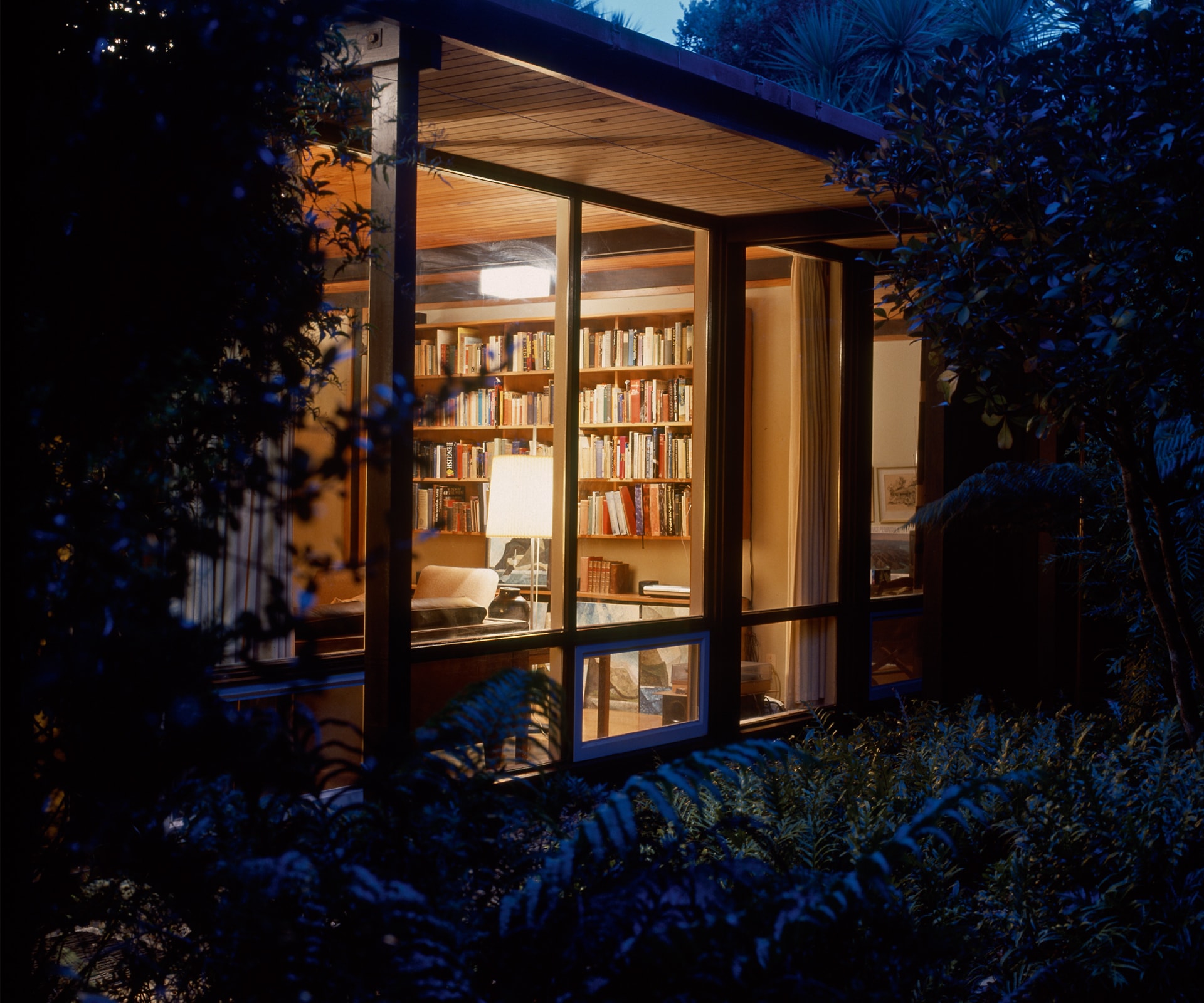

Brake House by Ron Sang, Titirangi, Auckland 1976

“The Brake House was also designed for a local celebrity: Brian Brake, the internationally renowned photographer,” Barrie says. “Ron Sang, the architect, produced a work of incredible clarity. It sits in the dripping Titirangi bush and is made of timber and is brown, but it deliberately eschews the cheerful quirkiness of homes like Athfield and Walker were producing. The Brake House’s hovering volumes ‘float’ right up in the treeline. It’s incredibly refined and smooth, the spaces crisp and everything is handled with the utmost dexterity. It’s a martini as opposed to a Lion Brown beer.” The home is now classified as a Category 1 Historic Place and is treasured by the couple who live there. SC

1980s

Ngamatea by John Scott, Kaweka Ranges, Hawke’s Bay 1981

“John Scott is the first really celebrated architect of Maori descent, but he always identified himself not as a Maori architect but as an architect of mixed heritage,” Gatley says. “Related to that, he identified Maori meeting houses and woolsheds as two building types that were important in New Zealand’s architectural history. Ngamatea is quite different from most of his houses, though. It’s one of the most overt statements about a building in a particular landscape. It’s in the rolling tussock of the Kaweka Ranges and it’s a pretty extreme climate. The house really hunkers down into this landscape with a pyramidal form that’s cut away in the centre with a very sheltered courtyard. Inside, there’s very conscious use of diagonal circulation from space to space, and a mezzanine which is open to the living spaces in the house which becomes a kind of communal sleeping space for family or friends or farm workers.” Ngamatea is still owned by members of the family who commissioned Scott to design it. BB

Gibbs House by David Mitchell, Parnell, Auckland 1984

“The Gibbs House is a very different take on internationalism. It marks the point of transition from modernism into postmodernism, where the house is conceived as a kind of collection of elements,” Barrie says. “David Mitchell was an early adopter of postmodernism and so the house is this collection of very different forms, materials and textures. A shiny corrugated ceiling, glass walls, shaped skylights and curved plaster bits combine to produce something that is incredibly glamorous. This would have been a highly sophisticated place in which to enjoy all the new things that were beginning to appear as a result of deregulation in the mid-80s.” The house won an Enduring Architecture award from the New Zealand Institute of Architects in 2015. SC

1990s

Mitchell Stout House by David Mitchell and Julie Stout, Freemans Bay, Auckland 1990

What makes the Mitchell Stout House for me,” Barrie says, “is that it isn’t so much a New Zealand house as it’s a Pacific house. There is water at the centre and the roofing is frayed at the edges in a way that you might find with woven coconut-frond roofing on a Pacific hut. It’s a little timber house with wider aspirations in that it shows New Zealand’s expanding horizons. This house isn’t so concerned about New Zealand-ness any more, but communicates greater comfort with the country’s place in the world.” The house is now owned (and adored) by architects Lance and Nicola Herbst. BB

Congreve House by Pip Cheshire, Takapuna, Auckland 1987–1992

“The interesting thing about the Congreve House,” Barrie says, “is that it is one of our first really sophisticated pieces of residential architecture. It was designed for educated clients with deep pockets and a truly international sensibility. It’s a very large, beautiful concrete house that’s intended to serve as much as an art gallery as a residence. It sits on a beautiful site overlooking the ocean and is a house of incredible, almost civic scale. It’s a building that is very attuned to what was happening internationally, but the architect has also been allowed to cut loose.” Adds Gatley: “It’s also very clear that Cheshire’s roots are not in Auckland, where the Group were constructing lightweight timber-framed buildings, but in Christchurch and the concrete and concrete-block buildings of Warren & Mahoney and Peter Beaven.” The house has sold several times since the Congreves moved to another Cheshire-designed residence. SC

2000s

Sky Box by Gerald Melling, Te Aro, Wellington 2001

“Both choices from the 2000s have got elements of brown bread and elements of sugar cube,” Gatley says, “which shows how the two strands are really quite interwoven by this time. Sky Box was a building Gerald Melling designed for himself. It really challenges norms of New Zealand housing – it’s really an urban statement of a domestic dwelling on top of an existing building. It’s tall and skinny with compact planning, and I think a great example of the sorts of things that we could be exploring more in our cities. It has an international flavour, but a ply-lined, hand-crafted, easy-going interior. The small footprint and verticality are quite different from New Zealand norms, but the timber-lined interior has a long tradition here.” Gerald Melling died in 2012. The Sky Box is now owned by his son David, who rents it out to a very happy tenant. BB

Cox’s Bay House by Nicholas Stevens and Gary Lawson, Cox’s Bay, Auckland 2005

“Thinking about brown bread and sugar cubes gets really tricky at this point,” Barrie says. He talks about “the collapse of this dichotomy of local versus international”, while noting that Stevens and Lawson often explain their architecture using images of New Zealand-ness – the dark boards, for example, harking back to Vernon Brown’s early homes. “But,” Gatley adds, “homes by Stevens Lawson are always very contemporary and beautifully detailed and have a sharpness or slickness that’s in the international tradition more than the regionalist tradition” By this stage, however, Barrie’s had enough of talking about architectural identity. “I don’t think it’s particularly helpful,” he says. “The real challenges are not to do with our place in the world but our moment in time. What I really want New Zealand architects to talk about is not ‘here’, but ‘now’.” SC

Words by: Jeremy Hansen.

[related_articles post1=”44373″ post2=”45182″]