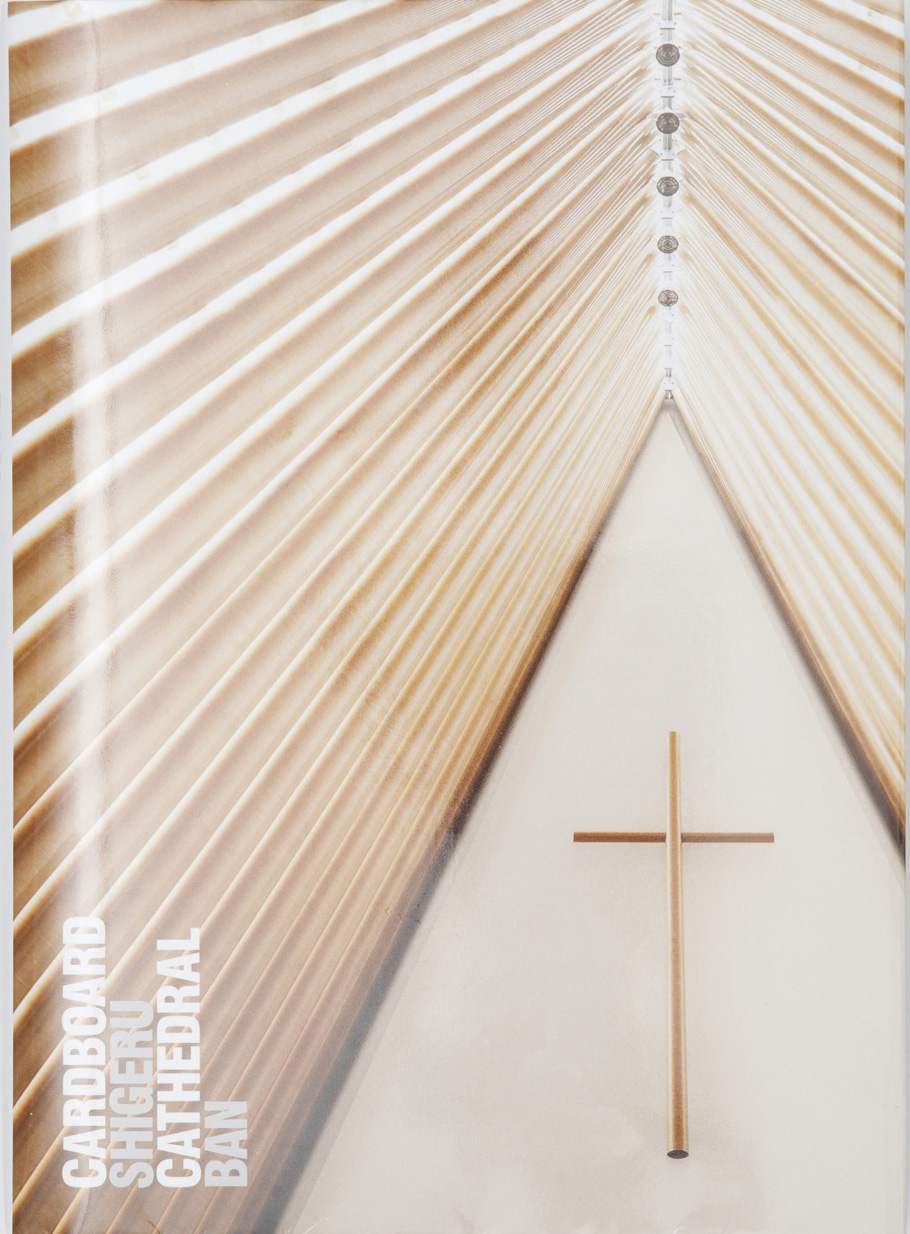

Christchurch’s Cardboard Cathedral is arguably New Zealand’s best-known work of architecture right now, thanks to the prominence of its architect, Shigeru Ban, who recently won the Pritzker Prize for his body of work. Andrew Barrie is an Auckland-based architect and lecturer at the University of Auckland who already knew Ban and was commissioned by him early in the process to write a book about the cathedral’s development. The book is out now, published by Auckland University Press. Here, HOME editor Jeremy Hansen interviews Andrew Barrie about the book and the Cardboard Cathedral.

HOME What made you want to do the book?

Andrew Barrie I’ve known Shigeru Ban since the late 1990s, when I was a research student at the University of Tokyo and he was producing his first work outside Japan. We’d kept in contact, and in 2009 I worked with the Japan Foundation to arrange a New Zealand lecture tour by him. Not long after work on the Cardboard Cathedral began, Ban got in touch to ask for help putting together a book on the design and construction of the project. Auckland University Press signed on, so I travelled to Christchurch every month to meet with Ban, conduct interviews, visit the construction site, and prepare the text. Since returning from Japan, it’s been my ambition to help connect New Zealand more strongly into the international architecture scene. I’ve arranged visits and lecture tours by lots of leading architects, many of them from Japan. So it was tremendously exciting to have Ban working here, and to see the project come together from close range. I’d like to think the Cardboard Cathedral is the start of what might become a steady flow of projects by leading international architects. Last year I did a project for the 5th Auckland Triennial in collaboration with Japanese wunderkinds Atelier Bow-Wow, and I’m currently working on a series of buildings for a central city Christchurch school with acclaimed Tokyo-based firm Tezuka Architects. Both of those projects flowed on from recent visits.

HOME Looking back on it now, does it seem like a miracle that the Cardboard Cathedral exists at all?

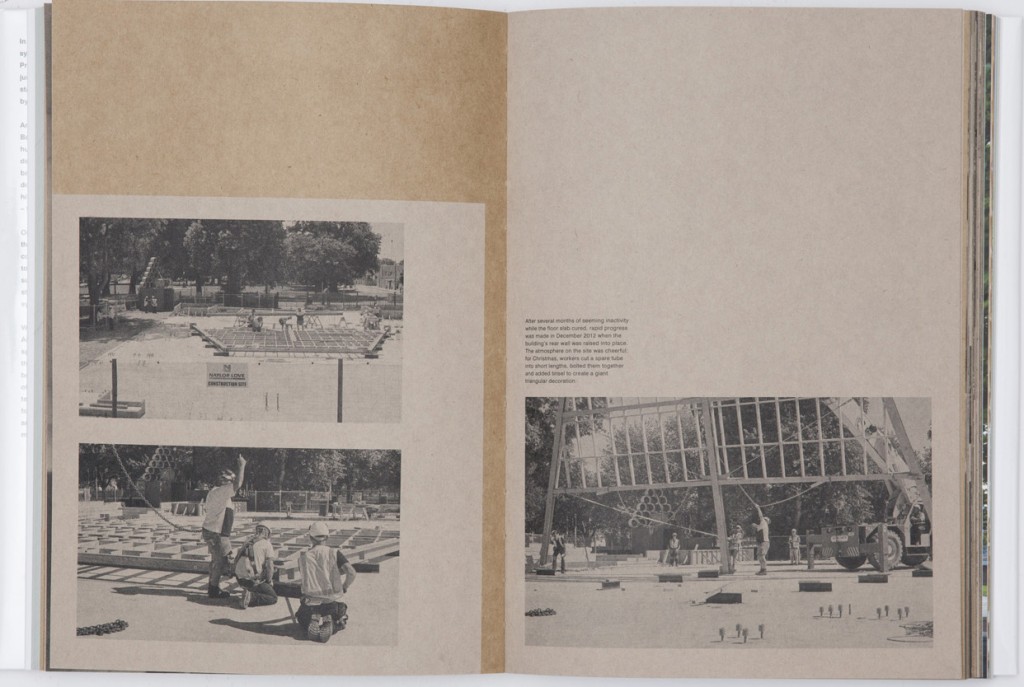

Andrew Barrie Yes. The initial hope was that a temporary Cathedral could be erected within four or five months, but the realities of the post-quake situation intruded. One of the slowest and most frustrating tasks had nothing to do with the building itself, but was finding a building site. You might imagine that in an inner city where 1,000 buildings have been demolished, finding land would be easy. However, the Cathedral team encountered a series of obstacles and dead-ends before getting agreement from the parish of St John’s to use the site of their quake-destroyed church. St John’s wanted to keep the building after the Cathedral congregation’s eventual return to their building in the Square, so the building changed from temporary to permanent, which required a major reworking of the design. There was also high-profile legal action – collateral damage in the fight over the Cathedral in the Square – that undercut the Cardboard Cathedral’s funding. In the end, the building took more than two years, but stands as testament to the energy and tenacity of a huge group of people – church leaders, architects, funders, engineers, project managers, construction crews, and so on.

HOME Structural requirements under our building regulations mean the cathedral isn’t as pure as its original conception suggested – the cardboard tubes, for example, cover laminated timber beams. Was this a disappointment for Shigeru Ban, and do you think it compromises the building at all?

Andrew Barrie The very first schemes for the building had a hybrid structure, with very long paper tubes reinforced by timber trusses attached to their top edge. This was changed not because of building regulations but because such long tubes could not be produced by local manufacturers and would have had to be imported. Using local materials is a key principle of Ban’s work, so the structure became shorter lengths of locally made tube threaded over big timber beams. The tubes still perform a key role in defining the light and character of the space. Actually, I’m perplexed not about the timber inside the tubes, but that there has been criticism of the change. Structural purity isn’t something normally demanded of buildings. Ban generally uses tubes as primary structure, but demanding he always use them in this way is like demanding that a chef only ever cook their signature dish, or that a musician only ever play their biggest hits. That would be dull for everyone.

HOME People talk about buildings putting places “on the map”. Has the Cathedral done this for Christchurch? What else do you think it has achieved for the city?

Andrew Barrie The Cardboard Cathedral has put Christchurch back on the map. It had long been a great city for architecture, with treasures by Benjamin Mountfort, Samuel Hurst-Seager, Peter Beaven, Warren & Mahoney, and many others. Back before the quakes, if you had one day to look at architecture in New Zealand, Christchurch was the best place to spend that day. In the Cardboard Cathedral, Christchurch now has New Zealand’s only building by a Pritzker Prize-winning architect, and my hope is that it’s the start of a new collection of architectural treasures. Further, I hope that it might raise ambitions. After the quakes there was a lot of talk about the rebuilding creating a model city for the 21st century, which is rhetoric we don’t hear so much now. The Cathedral stands as evidence that we can indeed achieve groundbreaking things.

Cardboard Cathedral Shigeru Ban by Andrew Barrie with photographs by Stephen Goodenough is published by Auckland University Press.