Sitting on the sand dunes, this angular new build encapsulates the spirit of the much-loved mid-20th-century batten-and-fibrolite bach

This Te Horo holiday home proves the classic Kiwi bach is not extinct

Now, this is how a beach house should be: wet dogs and driftwood, wet towels and sand on the floor, discarded boardgames and kids – lots and lots of kids.

It’s the school holidays and Kerry, her friend Philippa, and their combined broods of, oh, about a thousand excited primary-aged kids have just walked back from the beach to Kerry’s new Te Horo bach. They’re just in time. The sky is greywacke, Kāpiti Island has vanished in cloud and the fierce westerly nearly blows the kids through the beach-side sliding door. They rush off for hot showers.

It seems the death of the great Kiwi bach may have been exaggerated. This exuberant beach house by Gerald Parsonson for Kerry, her partner Richard and their family has a playfulness and craft that’s most certainly 21st century. But when it’s filled with kids and dogs, you sense the spirit of the much-loved mid-20th-century batten-and-fibrolite bach has been reborn. “That’s what we wanted,” says Kerry. “We wanted a bach, we didn’t want it to be fancy, we wanted it to be relaxed, laid back.”

Parsonson’s solution to his clients’ summery brief brings rare character to a coastal area, many of which have become lousy with recently built paint-by-numbers beach houses that look like they’ve been delivered directly from a city subdivision. Areas that once had character have been made suburbia by the sea for people who, paradoxically, are escaping suburbia in the city.

But what makes a bach? The late New Zealand novelist Nigel Cox, writing in New Zealand Geographic more than two decades ago, said that the classic form was rough as guts: an outdoor dunny, galvanised iron water tank, fibrolite exterior, unlined interior, exposed rafters and wiring, bare timber floors, paua shells on shelves, little piles of playing cards, a shelf of well-thumbed paperbacks. But most of all, the good old Kiwi bach was built on the cheap, and was utilitarian to its fibro soul.

What Parsonson has created here is quite obviously the very opposite of rough as guts – his attention to detail has been beautifully achieved by master builders and joiners – but the Te Horo bach has its carefully spent budget and determined practicality in common with its 20th-century forebears. So, too, its individualism.

“They wanted something with a bit of spirit, a bit of character,” says Parsonson. “But they didn’t want to spend a massive amount either – we worked really hard to keep costs down.”

Minimising corners was the first priority. The house is a rectangle, but there’s nothing simple about what Parsonson decided to do next. “The most inexpensive way to build a house is a trussed roof banged across a row of flat walls – take a drive to the suburbs,” he says. “I started thinking about that construction, how to make it interesting, but still keep the economy.”

The solution was inventive. Viewed from the beach, the slanting roof is low key: Parsonson created a long monopitch roof, which kicks out over the eastern wall on the leeward side with an elegantly sloped soffit that angles out from the wall. Inside, there are flat ceilings in the bedrooms, while in the living areas there’s a pitched ceiling to provide a bit of height. It’s a playful approach that turns a simple box into something special.

The slanting roof is also practical: it pushes the prevailing wind up and over the house. Combined with exterior white battens and fibro walls in alternating colours, the effect evokes grass bending in the wind, or perhaps a wind-sheared tree.

“It wasn’t literal, but it was referencing those things. I’ve always been fascinated by the shop fronts in provincial places like Otaki and Levin, where the windows lean out or in.”

The fibro-and-batten construction has also been given rhythm by rolling battens up and over the house, including the windows in some places. This same language follows inside, where battens roll up the walls and across the ceilings – like the floors, they are Okoume plywood. Extended battens form grids in the bathroom, WC and laundry, too, subtly alluding to the unlined walls of a traditional bach, while also providing narrow shelves for, say, a tube of toothpaste or a shell from the beach. The effect is very handsome indeed.

[gallery_link num_photos=”13″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/TeHoroBach_Dec2018_10.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/angular-bach-beach-location-clever-design” title=”See more of this holiday home here”]

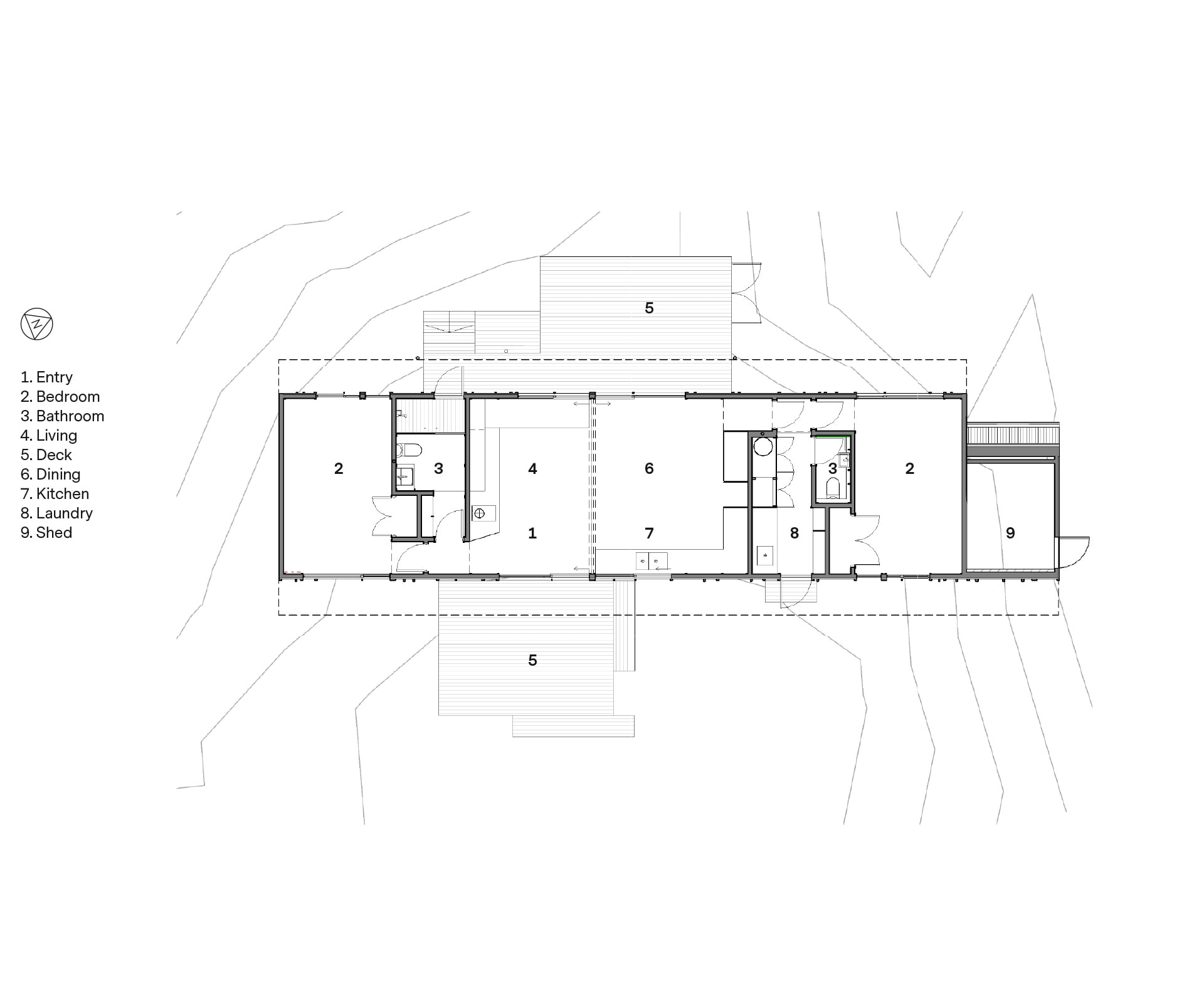

The open-plan living space is the home’s centre. Two bedrooms bookend the house with the bathroom and laundry spaces sitting between each sleeping space and the living area. Parsonson has used a pinwheel pattern in his design so that, for example, the L-shape kitchen bench is diagonally opposite an L-shaped window seat in the living space, while the shapes of windows reverse sides the bedrooms. Clever and playful, but also practical.

In the children’s bedroom, which has beautiful bespoke double bunk beds, there are floor-to-ceiling windows and louvres looking to the sea and a smaller, lower landscape-shaped window on the leeward side. To get a sea view in the main bedroom, you have to be lying in bed to look through the low landscape window, which suits Kerry just fine. Although the bach looks across the dune-scape to the beach and sea, she wanted to limit the amount of glass.

“We didn’t want sun streaming in all the time,” she says. “I like to get away from the sun, I want to be able to read a book without wearing sunglasses.”A practical solution to a coastal site dominated by sun and wind is sheltered decks. The windward deck offers views of the Tasman and, just to the south, the rugged drama of Kāpiti Island. The leeward deck provides shelter from prevailing westerlies.

“One of my favourite places,” says Kerry, “is on the back deck looking diagonally through the windows and sliders out at Kāpiti, while Richard likes sitting on the front deck looking directly toward the island.” That’s what a bach should be, too, one supposes – somewhere you do as you damn well please.

Words by: Greg Dixon, Photography by: Paul McCredie.

[related_articles post1=”42179″ post2=”77800″]