Lisa Webb creates a home of intrigue and shadow on a tiny scrap of land that was formerly a front lawn

For a moment, coming in from a bright Auckland afternoon through the timber-lined entry of architect Lisa Webb’s home, your eyes take time to adjust. Slowly, the house reveals itself as you round the corner – a black ceiling, rimu lining and dark blue walls come into relief. The effect is almost painterly, with the hues of an old Dutch master. Colours are warm and saturated. Shafts of light enter through deliberately placed windows and skylights, to exist as almost solid objects inside the space.

There are quite a lot of walls. The entire house feels cocooned, pleasantly inward facing, but not claustrophobic. “I feel comfortable in enclosed spaces,” says Webb. “I like feeling my back against a wall. For me it’s a physical sense, the way you feel a space. It’s one of the reasons I became an architect – because I felt physically different in different spaces.”

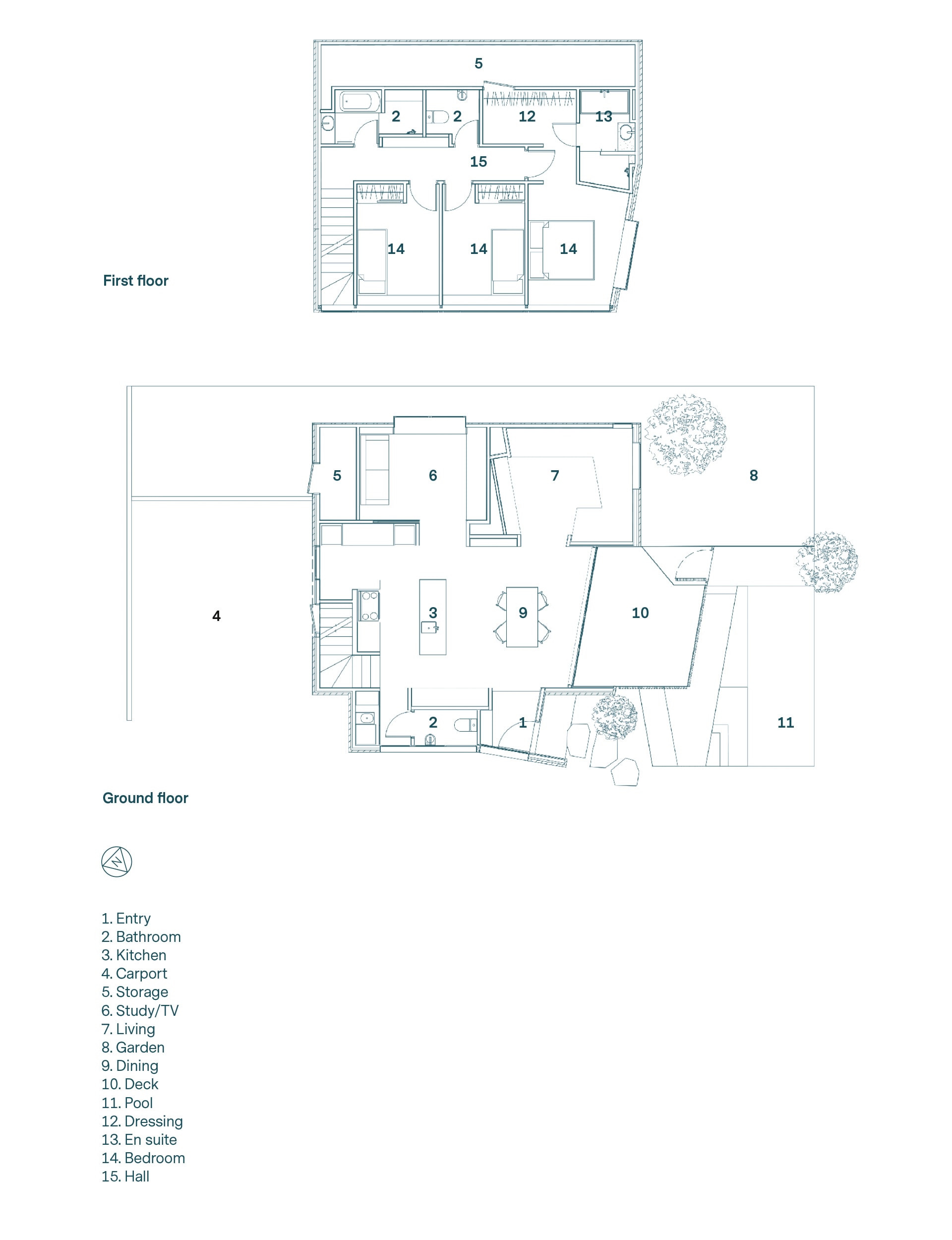

It’s also a deliberate response to the tiny inner-city Auckland site on which the house sits. Webb and her husband Alastair Pope were renting a rambling old bungalow on a 1000-square-metre site across the road when, in 2015, this section came up. It’s 332 square metres, of which only 200-odd are buildable, thanks to a driveway that’s shared with the house behind. It was covered in covenants to protect the view from the original house, and while it was flat and got good sun, north was straight out front, to the street.

The upside? It wasn’t an old house in need of an expensive alteration, and the difficulty of the site was such that developers and spec builders couldn’t make it work. After doing some brief sketches as part of her due diligence, Webb knew that she could. Though her daughter was less confident: when she learned the family was moving across the road and onto a former front lawn, she cried.

The key to making it work was to very subtly make every space slightly smaller than you might otherwise think it needs to be. “It means everything has to work really hard,” she says. “I just didn’t have the ability to build a big room with space around the couches.”

From the street, it has a withdrawn, even intriguing presence. Built from warm white bricks that catch the shadows, there’s an asymmetrical gable pulled down low and tight on one side, higher on the other, and punched out with deep-set black windows and timber reveals. The site feels public: there’s the driveway down the side, and the northern aspect faces the street. It’s not exactly forbidding, but there’s a sense of remove and restraint that is very deliberate – while the downstairs living areas run out to the front garden, the doors are set back inside timber reveals and the front wall is as high as they were allowed to build it.

Downstairs: a kitchen-dining area, with black-painted Strandboard cabinetry and a black-painted cross-laminated timber ceiling that also forms the floor of the level above. This arrived in a day, cost less than other forms of construction, and, at 160mm thick, saved much-needed space in the tight design. To these humble materials – more often covered up with fancier finishes – Webb added a spectacular white-marble kitchen island.

[quote title=”In many ways, it’s a return to a more broken plan,” green=”true” text=”a way of living we might have seen in the 1970s.” marks=”true”]

Off this room, there are – unusually – two smallish living rooms. One for the kids, and one for the adults. The latter is a cocoon of rimu, with a generous built-in sofa that wraps three sides of the room. Webb fondly remembers one of the first houses she ever designed, fresh out of architecture school.

It was an old villa in Grey Lynn that she and her friends were flatting in. “We blew out the back and built a party room – it was amazing,” she says. “And then you get older and have small children around who watch Teletubbies while you’re trying to have a quiet cup of tea and one big open space starts to become problematic.”

In many ways, it’s a return to a more broken plan, a way of living we might have seen in the 1970s, when parents retired to a room separate from the rest of the living areas. But it’s an approach that has fallen out of favour for open kitchen-living-dining areas.

“We lead really busy lives,” says Webb, “and I’m not going to pretend I read books or listen to Wagner in there – it’s Game of Thrones! It was important to have that hour or two at the end of the night to watch TV.”

[gallery_link num_photos=”15″ media=”http://www.homestolove.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/HE0619_H_Westmere-House_75A0709lrg.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/beautiful-family-home-small-piece-lawn” title=”See more of this home here”]

From the kitchen, a set of black-painted Strandboard stairs lead to the second level – three compact bedrooms down the eastern side, and service rooms down the west, tucked in tightly beneath the gable. It’s richly comforting, with blue-painted plasterboard walls and mustard carpet. In the bathrooms, stone tiles are cut from boulders pulled from an Aoraki river. And there’s a soaring ceiling that follows the roof pitch and makes the space breathe.

In this house, Webb has got away with creating spaces that, while small, don’t feel cramped. “The spaces have to work really hard and they don’t have to be that big,” she says. “Would it be better to have a bigger bedroom? Maybe. Do you need a slightly bigger bedroom? No.”

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Sam Hartnett

[related_articles post1=”65799″ post2=”94820″]