A Wanaka home designed by Wellington-based firm Lovell & O’Connell Architects is a bold, distinctive design on a street of nondescript houses

Concrete, cedar and ply combine in this Wanaka new-build

It is all very well to design homes with enormous budgets on spectacular sites, but architecture is in dire need of more prosaic locations.

There are suburbs all over New Zealand where architecture barely makes an appearance, where even basic, age-old design lessons like the correct orientation of homes to the sun have been mostly ignored. Whatever the reason for architecture’s near-total absence in these places, everyone ends up the poorer for it.

Hiring an architect to design their new Wanaka home came naturally for Doug and Kate Lovell, as their son Tim had recently established the Wellington-based firm Lovell & O’Connell Architects (LO’CA) with Ana O’Connell, an old friend from architecture school. (Tim had most recently worked at Wellington’s Parsonson Architects, while Ana had been part of Jasmax’s team in the capital.)

Doug and Kate were moving out of a home on the Otago Peninsula designed for them 40 years earlier by Murray Cockburn, a Queenstown-based architect they would have happily commissioned again had their son not entered the profession. They had decided to retire to Wanaka after holidaying there for decades. For their new home, they purchased a site in a new subdivision on the eastern side of the lake with views across the water towards Treble Cone.

The home Tim and Ana designed for them – a finalist in the Home of the Year 2014 – was one of the first in the suburb and it set a high bar, a bold, distinctive form in a street now full of dwellings with few distinguishing features. “When we started with the design there was nothing else in the suburb to respond to, so we started looking at the landscape and the history of Central Otago,” Tim says.

The pair was particularly inspired by old miners’ huts in the region, which sometimes featured a wall of schist and a single sheet of corrugated roofing iron. “They were very simple structures that provided real shelter in an exposed landscape,” Tim says.

Their first move was counter-intuitive in a suburb where most of the homes now seem to be craning their necks for the view: they cut into the site and lowered the building platform of the home by about a metre, which makes it feel safely hunkered down on its windy site. Most of the soil from the cut was moved to create a softer transition between the house and the road, and to provide more shelter for the site from the northerly winds.

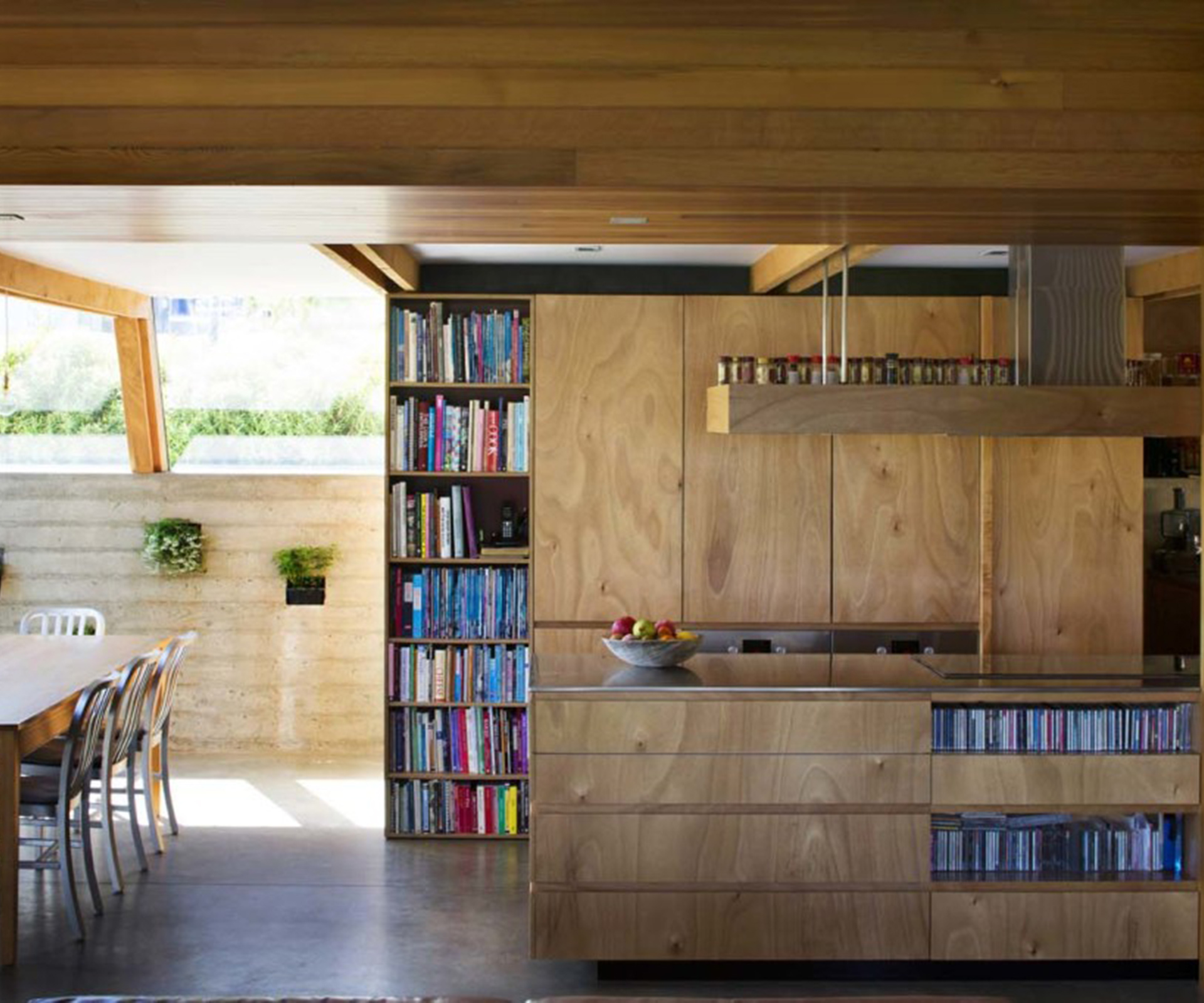

Near the street, they designed a long, low, thick concrete wall – a reference to the schist walls of the miners’ huts – which runs from inside to out and enhances the sense of the home being firmly grounded and sheltered. The elemental feel of the wall, which was cast on-site, is enhanced by the inclusion of cut-outs in which Doug, a keen cook, can grow herbs. The plants, which spill down the concrete face, make the wall feel like a part of the landscape.

The home’s dark steel roof leaps off this concrete base, forming a wall of privacy to the street and folding protectively over the interiors. Its centre is cleaved apart between the garage and kitchen to form a tranquil entry courtyard that catches the morning sun, while a second courtyard opens off the north-facing dining area under the peak of the steep roof.

A living area faces the lake view, while two guest bedrooms and a bathroom are tucked above this on a mezzanine level. Doug and Kate’s bedroom and bathroom are on the ground floor, past a snug den where Kate plays her double bass, and where specially designed cabinetry holds treasures from their old home, including a grandfather clock and a collection of first-edition books. Doug’s antique desk occupies the corner.

The house measures 250 square metres including the large double garage, but its efficient planning makes it feel larger. With a limited material palette of concrete, cedar and interior ply walls, the house was immaculately constructed by builder Tony Quirk for a pleasingly economical cost.

The home functions beautifully, positioned perpendicular to the prevailing northerly wind so that it runs along the front face without gusting inside. Low west-facing eaves mean the home never overheats in the middle of summer, while collecting plenty of solar warmth in its concrete floor in the winter.

There are some risky dynamics in play when an architect designs a home for his or her parents, including the possibility that the younger generation will impose a vision of how they think their elders should live, rather than genuinely responding to their needs. Kate and Doug had done a test run 12 years earlier when Tim designed a renovation of their bathrooms in their old house. “They were beautiful and were an important part in our house selling within 10 days,” Kate says.

Ana was there to ensure all the family members were listening to each other. “Doug and Kate came to the project with a lot of trust,” Ana says. “There was a lot of discussion about how they wanted to live as a retired couple.” Tim also had the advantage of knowing how Kate and Doug live, while being mindful this was a time of great change. “This was a new way of living for them because the day they moved in was the first day of their retirement,” he says. And when you’re designing for your parents, the long-term consequences of not getting things right can be a great motivator. “If we’d cocked it up,” Tim says, “I would never have lived it down.” -Jeremy Hansen

Q&A with Tim Lovell and Ana O’Connell of Lovell O’Connell Architects

HOME The Wanaka subdivision has some great views, but when you embarked on this project you couldn’t see where other homes were going to be located. How were you able to respond in this situation?

Tim Lovell The house has a walkway on its northern side. Because we knew that key view wasn’t going to be built out, we focused the house on that view down the lake towards Treble Cone.

HOME What was it like designing for your parents?

Tim Lovell It was good. They were the best clients I’ve ever had. I think as an architect you need to find out about your clients and how they live, and I already knew all those things so we had a lot to design from. I don’t think we pitched an idea they said no to. A key element of the house was they wanted to do more entertaining, because they had more time. My Dad loves to cook, and I remember when I was younger he’d often be stirring a pot with his back to us. So in the new house we flipped that around so he can talk to people.

Ana O’Connell It was almost like a bit of a stage for him – the cooking is a performance.

HOME The home you’ve designed has a bold form. How did you develop it?

Ana O’Connell We looked into the history of the place, and these beautiful miner’s huts with a wall of schist and then a draped corrugated roof – very simplistic structures that provide real shelter in an exposed landscape, and have a pared-down material palette that’s just so strong. So we came up with this idea of a rock frame and roof being the main parts to design the house around.

Words by: Jeremy Hansen. Photography by: Paul McCredie.