Inside her Grey Lynn apartment, gallerist Sarah Hopkinson shows us how to live in harmony with challenging contemporary art

Contemporary art takes centre stage in this lofty Grey Lynn apartment

Even for dedicated appreciators, a relationship with contemporary art is usually divided into two distinct contexts: the home, where paintings, drawings and prints hang on walls and we come to know them in detailed, intimate ways; and galleries and museums, where sculptures, installations, performances and videos sit on plinths, hang from ceilings and fill pitch-black rooms to be seen once or twice and never again. And while we might be more interested in the challenging work of the gallery and the museum, when it comes to living with art, we retreat to works that can rest safely on a wall and not get too much in the way.

For gallerist Sarah Hopkinson, who runs Hopkinson Mossman in Auckland with Danae Mossman, the apartment she lives in behind the gallery is an opportunity to breach those barriers and, in the process, provide an example for clients of how to live with challenging contemporary art.

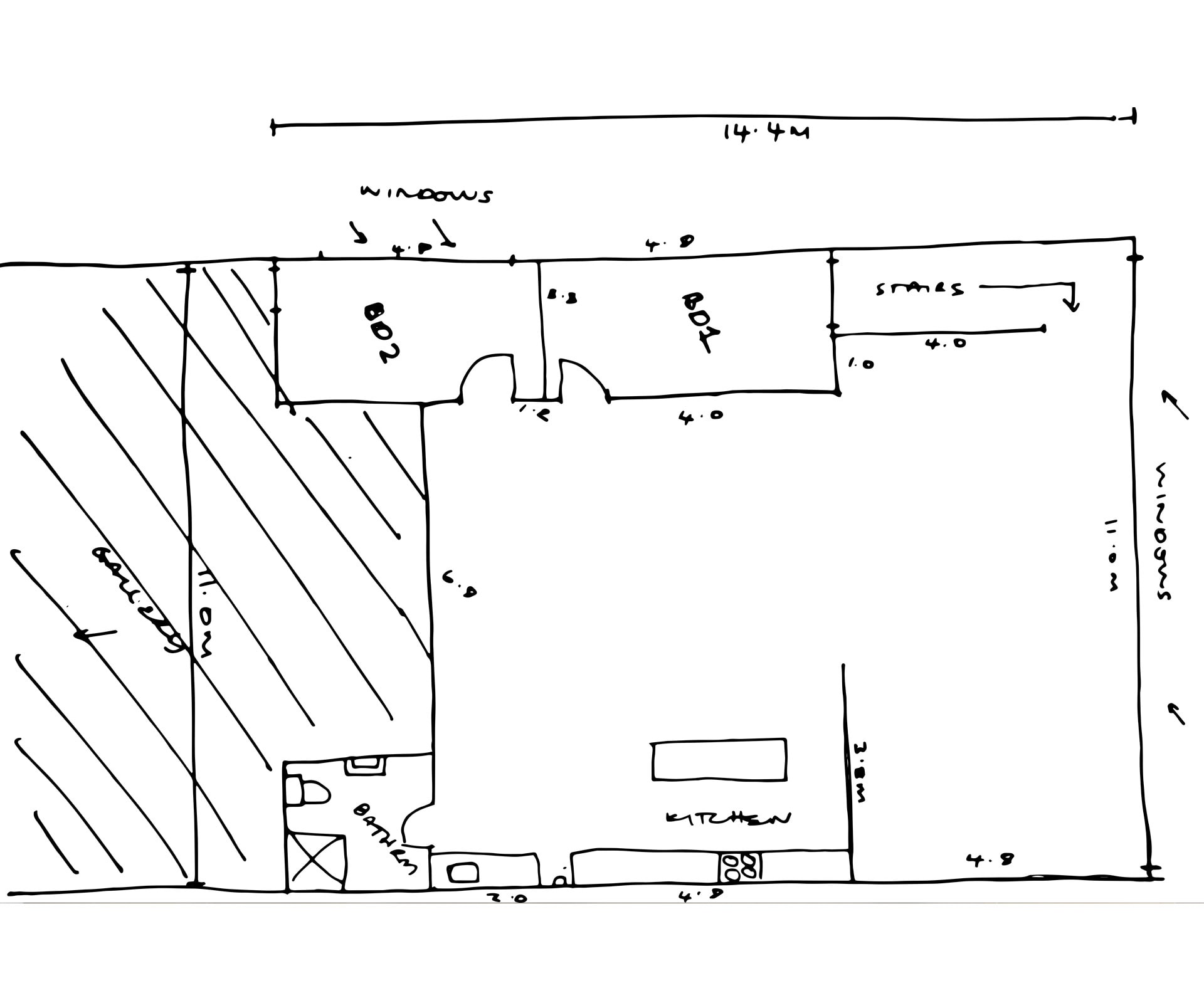

When Hopkinson Mossman took the lease on its Putiki Street gallery, above a mechanic in an industrial block in Grey Lynn, the landlord offered them the option to extend the lease to the whole floor, which meant the gallery could expand should it need to. The gallery wasn’t ready to expand, so they used the space as a stock room and an apartment for Hopkinson. Made up of a large, open living area partially divided by a temporary wall, and two small bedrooms, the home has wide windows that offer a panoramic view to the harbour, flooding the living space with light when the sun is low.

Along the north-eastern side are two bedrooms, one of which leads to a stock room and then the gallery. Hopkinson added the industrial kitchen – the stainless-steel benches and plastic crates sourced from a hospitality wholesaler, and a powder-coated zinc-oxide kitchen island from fashion designer Liz Wilson, who used it as a counter at her formershop, Eugénie, in Ponsonby.

It feels sparse, but not minimal. There’s one couch, a circular dining table and chairs, a collection of plants in a corner, as if in a glasshouse. There’s almost nothing decorative. Other than art. “I like nice furniture, sure, but it’s just not a priority for me,” says Hopkinson. “If I think about what I find most satisfying to live with, it’s always contemporary art. I’m very aware of not having a house that seems too tasteful. Contemporary art should be challenging. If it isn’t, why wouldn’t you just spend that money on design?”

And there’s art everywhere, mostly by artists represented by the gallery, and much of it borrowed from the stock room and swapped around when the mood strikes. Right now in the stairwell to the exit are five large Peter Robinson felt sticks that are nearly two floors tall. By the entrance is an imposingly heavy sculpture by Fiona Connor, a faithful facsimile of a noticeboard from Silver Lake Park in Connor’s adopted home of Los Angeles. It looks freshly ripped from the ground. Near the kitchen is a table with a thick hand-latch-hooked rug by Ruth Buchanan, a reference to a mural Le Corbusier painted in Eileen Gray’s house without her consent.

Nearly everything in the apartment is large, colourful and expressive. “Because it’s so open, you can’t really put small things in here. Or you can put very, very small things or very, very big things. But if there’s contemporary art on the wall, you don’t really need much else,” says Hopkinson.

The most prominent architectural addition to the space is the zigzag wall, which Hopkinson designed, taking inspiration from 1990s post-modernism and Memphis Group design. While it serves to contain the kitchen area, it feels more sculptural than functional. The wall sits opposite a chain curtain called ‘Split, Splits, Splitting’ (2006) by Ruth Buchanan, from an exhibition at Wellington’s Adam Art Gallery. “Ruth’s work is very much about the body and how it negotiates space,” says Hopkinson. “She makes work where you brush up against things. At the Adam, you walked through this piece. Everyone who walks in touches it – it’s an industrial material, there’s nothing fragile about it.”

The curtain also acts as a room divider and light filter. When the sun shines in and hits the chains directly, the curtain appears solid if your back is to the light. Viewed from the other side, it looks transparent, almost disappearing completely, other than the speckled light it projects onto the floor and walls.

The house is filled with sculptural works that, like Buchanan’s mesh curtain, impose themselves on the space and transform the apartment. Hopkinson gets to know work in ways you don’t in a gallery. After most openings, the gallery holds a supper for friends, supporters and clients, turning the apartment into a lived-in extension of the gallery.

[gallery_link num_photos=”13″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/chapel9.jpg” link=”real-homes/home-tours/auckland-apartment-lofty-warehouse-style” title=”See more of the apartment here”]

“We think there is value in collectors seeing art lived with in ambitious ways,” she says. “Contemporary art asks you to think about how you live with it. I can install a massive work here – institutional-scale pieces. I’m super-lucky – I have a stock room just there,” she says, pointing towards the door to the gallery. “So if, on a Sunday, I feel like rehanging, I rehang.”

Words by: Henry Oliver. Photography by: David Straight.

Words by: Henry Oliver. Photography by: David Straight.

[related_articles post1=”72818″ post2=”72832″]