Tasked with creating an extension to this former 1950s Statehouse that could be used as a multi-room, but was not allowed to be a brick-and-tile double garage, architect Mark Frazerhurst looked to curves and corrugated fibreglass

Project

Studio addition

Architect

Mark Frazerhurst

Location

Point Chevalier, Auckland

Brief

Create a multi-functional room and extra bedrooms for a growing family.

Sometimes, beautiful things come from the most prosaic of beginnings. In the case of this addition by Mark Frazerhurst to a home in Point Chevalier, Auckland, the owners wanted an extra bedroom or two, and somewhere to park the car. But no one wanted a brick-and-tile double garage out the front of the 1950s former State house. “Our initial response with any renovation project is to do something that is of now,” says Frazerhurst.

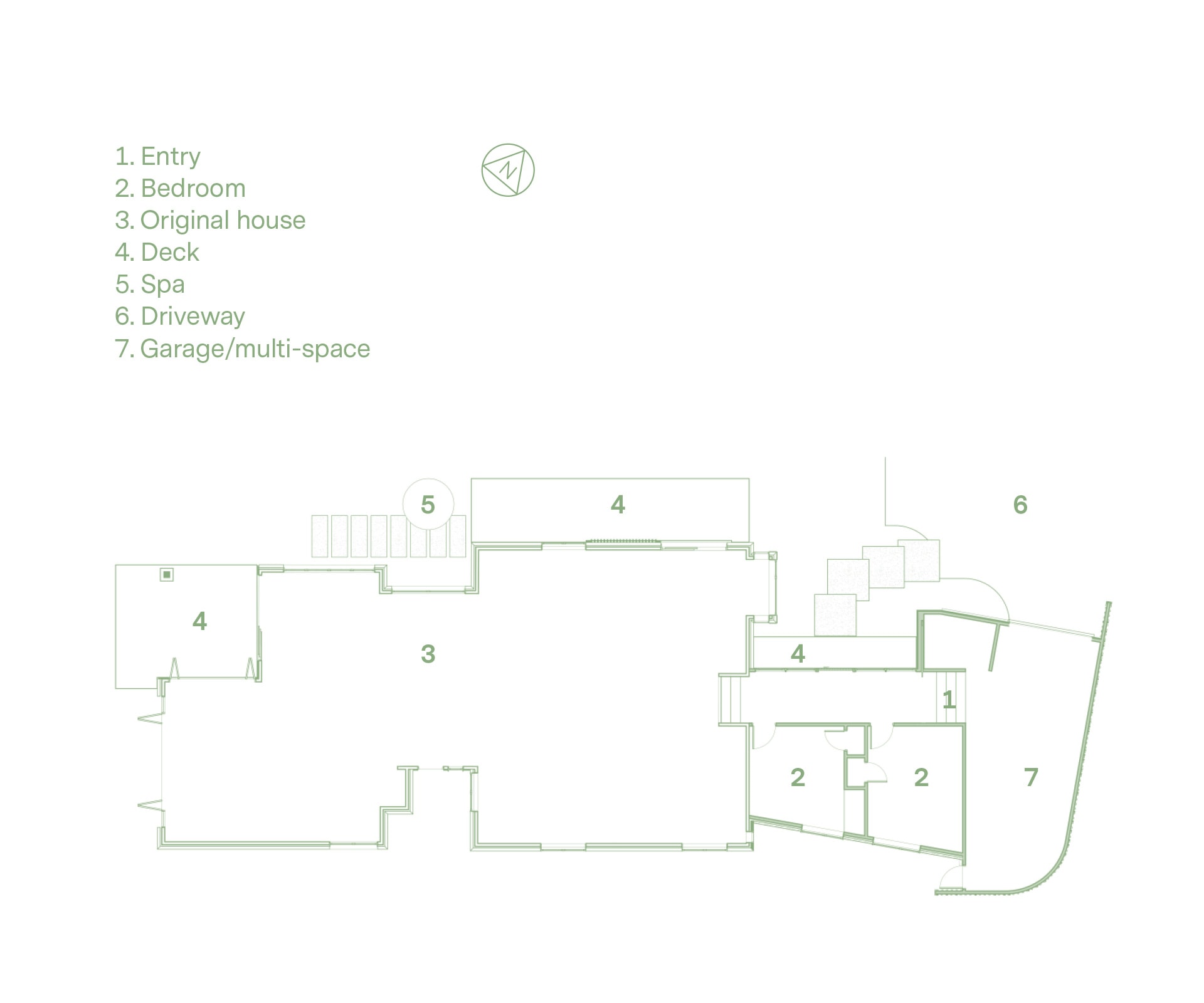

The original house was a small affair that had been significantly altered by previous owners – most recently an extension out the back, containing an open-plan living area in keeping with the original house. It was in good condition and perfectly functional.

“It had all the bones. You had a big, under-utilised eastern side and a private area out the back, but it otherwise worked really well,” he says.

The house sits in the middle of the section, so the architect’s moves were effectively limited to the front, with its generous – if under-utilised – yard. Frazerhurst was determined to create something floaty and ephemeral, rather than solid and bricky: a counterpoint to the original house, and sitting a couple of steps below it at ground level. “It lent itself to the flow of a curve and an angle to the street, rather than a solid rectangle,” says Frazerhurst. “But the angle is subtle, really subtle.”

He came up with a semi-enclosed garage – somewhere between a carport and garage. Corrugated fibreglass Durolite panels with cedar battens sit outside the building envelope, letting in light by day and allowing the room to glow at night. Although the project started out as a garage, it developed, becoming more ‘dressed’. Clad with ply, and with a polished concrete floor, it’s a bit nice for cars and has more in favour with yoga, boxing bags and ping pong.

Next to that, a modest extension is clad in raw Eterpan fibre cement and lined with cedar on the inside. It contains two bedrooms and an elegant long gallery entry that extends the original hallway and replaces the old front door. The extension also reworks the entry sequence. The house is now approached via meandering poured-concrete steps, then into the glassy gallery lined in oiled cedar battens, which conceal doors to the two new bedrooms.

In the original house, Frazerhurst turned a bedroom into a games room, and built a long deck off the northern side, but largely left the home untouched – he’s learned through a number of renovations to limit the impact on the original as much as possible. (On this project, he removed just one window.)

Both structures are lightweight, contemporary, cohesive counterpoints to the original house. Standing at the back of the house, you can gaze down the cedar-lined gallery and out to the opaque fibreglass studio – a long, light-filled procession through different decades. “We wanted to give back to the street,” says Frazerhurst, “and we wanted it to be a sculptural object.”

Q&A with architect Mark Frazerhurst

What do you look for in a new material or product?

We’re always on the lookout for new products and materials, as well as alternative and innovative ways of using existing materials. We’re becoming more and more conscious of trying to source locally. We’re out to create architecture that’s more accessible to everyone, but I’m a firm believer in you get what you pay for, so quite often the cost-benefit analysis is a complex decision during the course of the design process.

You’ve said you often try to make additions that are clearly from now – why?

We design architecture contextually; a design is a response to place, personality, brief, but also temporally responsive. We also try not to emulate. We live differently now than how we did in the past – often in the formal-informal sense. Inwardly focussed, singular use, non-interconnected spaces don’t necessarily work with the idea of casual multi-purpose living. I also feel it’s respectful of the original building to complement an historic aesthetic by not creating additions that imitate the original.

You’ve chosen materials on Moa Road that are different yet somehow sympathetic – how do you make that distinction?

It’s all about composition and balance. Architecture is an art – it’s the process of making spaces conceived as a composition of form, light, colour, materiality, texture, weight, and so on. A home should also be a balanced composition. On the Pt Chevalier home, we read the existing painted brick ex-Statey as the heavyweight anchor, and added complementary lighter-weight forms and materials – Durolite translucent cladding to provide natural light in place of windows; varying-profile cedar battens for warmth and texture; concrete floors to balance the existing timber floorboards; and sealed natural Eterpan as a non-competing counterweight between the brick, timber and translucent sheeting.

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Aimee Preston

[related_articles post1=”88159″ post2=”54558″]