The Herbst bach on Great Barrier Island turns 20 this summer. Simon Farrell-Green looks back at how this project was instrumental for their career

There are houses that stay indelibly imprinted on your brain. You can remember every step you took, every footfall despite having only been in them once or twice. They become familiar, like a house you’ve spent a lot of time in. For me, one such place is the bach of Lance and Nicola Herbst on Great Barrier Island. This summer, it turns 20 years old.

You might know it from the reportage it has received over the years, and for the effect it had on New Zealand architecture and the Herbsts’ careers. Back in the early 2000s, the couple burst onto the New Zealand architecture scene after emigrating from South Africa with a style of building – all outdoor rooms and screens, outdoor fireplaces and methods of building, where the bones of the house seemed elegantly on display. It was foreign yet uniquely New Zealand. It belonged here, a version of the New Zealand beach house; familiar and strange.

I first visited a few years back with Nicky’s sister Jackie Meiring: the house was closed up, hibernating. I visited again at the beginning of this year while judging Home of the Year with the Herbsts, and Gloria Cabral, our international judge. You don’t just arrive, open the door and turn things on here: you have to unlock padlocks and open big wooden doors that turn into walls, and slide back the shutters and set the fire for dinner. There’s a ritual to this place, a series of moves you have to make before it functions.

I went for a swim, and when I got back there was a gin waiting for me. We sat outside until late with the fire blazing. We didn’t do the dishes, because in South Africa that means your hosts want you to go home.

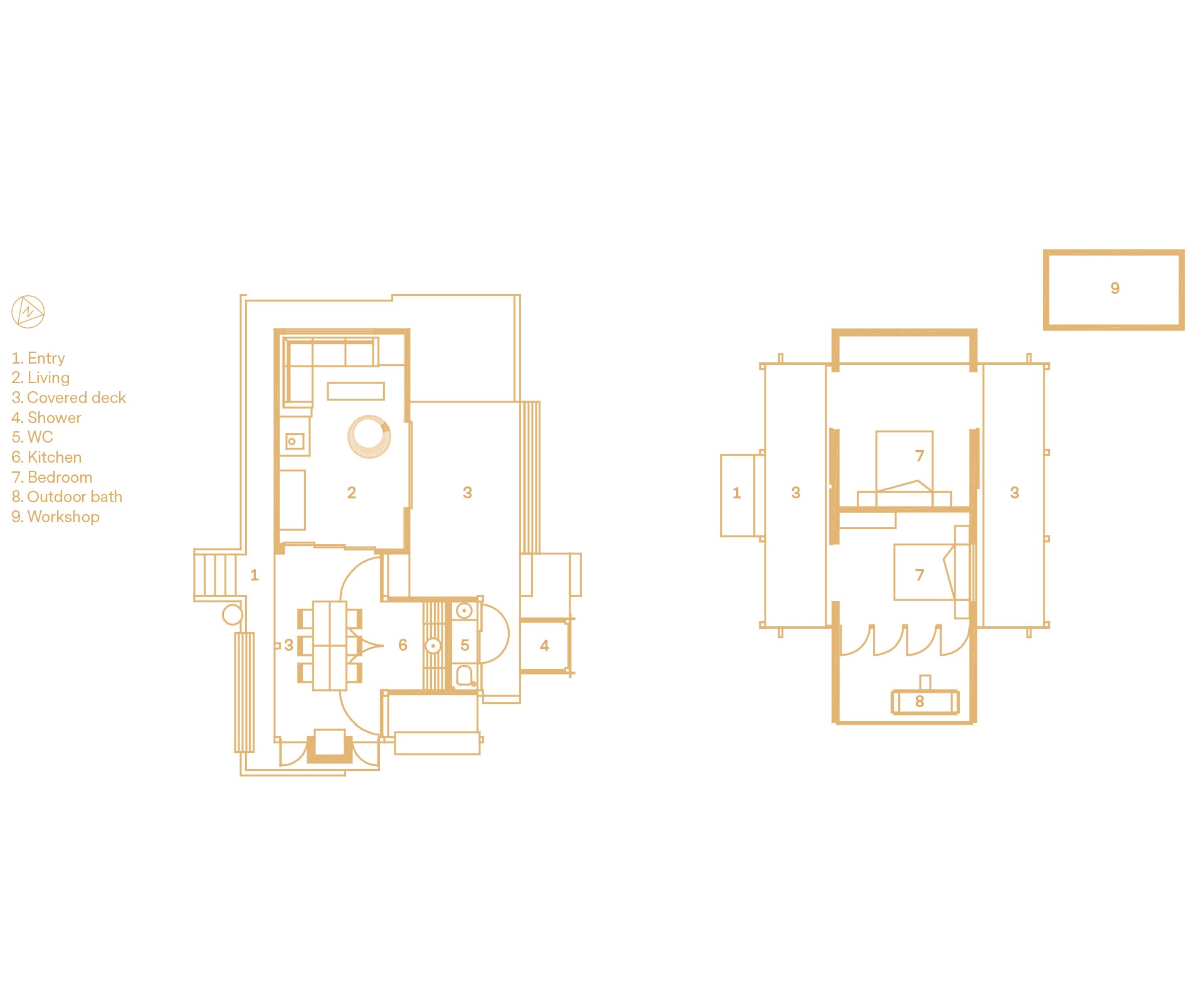

Lance and Nicola first visited the Barrier in 1995 and bought land in 1999, shortly after moving permanently to New Zealand; they built the first part of the bach in little more than a month: a tower with a butterfly roof and a water tank on top of a little ablutions block – kitchen one side, bathroom the other – that opened out like a Swiss Army knife. It had an awning above a deck, and they cooked over an open fire and slept in a tent.

The tower was meant to be stage one of a house that would be built at the top of the section, overlooking the dunes to the sea. “As soon as we built the tower, we said, ‘No, we’ve got this wrong. We want some space between the road and us,’” recalls Nicola. Due to a surveying error, they didn’t realise it would be quite so hunkered down. On one side it sits cut into the hill behind a low retaining wall; on the other the lawn drops gently away. “We just loved it. It’s really nice as an edge – seeing the horizon, the grass. Instead of looking down on the lawn, you look at it above your eyeline. And we pretty quickly decided it would be this.”

The next year, they built a covered deck in front of the kitchen, along with a one-room space that doubled as living and bedroom; another year later they installed screen shutters that slide to enclose the deck and dining area. That was it for several years, until 2007 when, down the back of the section, they built a two-bedroom sleepout, which houses their own bedroom, with an enclosed deck and a generous verandah.

The spaces are small, but powerful. While it still has its original feel, they tinker endlessly with the place; Lance likes to find a project a year to keep himself busy. A few years ago, they built a cedar bath for their bedroom courtyard. Soon they’ll build a second bathroom in the sleepout; trekking to the composting toilet in the middle of the night isn’t ideal.

They had toyed with three different schemes for a covered deck at the back, before deciding it was too much. “We worried it would start to lose the very thing that gives it life,” says Nicola. “Every change we’ve made has been incremental.”

They tell stories of the place with the aid of a visual diary. There was the summer the northerlies howled in; the next year, they built a series of timber flaps to enclose the gap between the sliding screens and roof. One year, there was a fire on the island and outdoor fires were banned; the next year they built an enclosed fireplace which is still where they do most of their cooking. Another year, they wanted to get rid of the gas fridges – one for booze and one for food – so they beefed up the solar panels. They had wifi for a time – until they received too many emails in one day, so Lance grabbed the pliers and disconnected it.

The year Lance turned 50, they wanted to entertain on a long table that would go from the dining area to the living area, which meant they had to change out the ranchslider for a series of stackers – “about as sexy as it got in 2000”, says Nicola. A few years later they replaced another ranchslider with a large, elegant sliding door that pulls back over the outside of the bach.

[quote title=”The work we’re doing now is light years away from this, ” green=”true” text=”but it has its seeds and DNA.” marks=”true”]

There’s a constant balance between convenience and comfort, evolution and stasis. “It would have been easy for us to knock this over and build a real house,” says Nicola – and often, structures like this do give way to a real house. “But we’ve decided not to,” says Lance. “Whenever we come out here, there’s something unchanging about it. Even what we’ve done here, it hasn’t changed. And the island hasn’t changed.”

The bach was instrumental in their joint career – it led to a number of commissions on the Barrier, which led to bigger projects elsewhere, and a reputation for being the go-to creators of holiday homes and retreats. Invariably, they have rooms that are outside but enclosed and heated by a fire, or inside but able to be opened completely to the outside. “The romance we talk about – this is real. It does still affect us,” says Lance. “The work we’re doing now is light years away from this, but it has its seeds and DNA.”

One thing hasn’t changed: their deep, underlying connection and dedication to the island. “For us, personally, it’s the most valuable thing we’ve done as a couple,” says Nicola. “Its tentacles are so deep into us, our whole lives are spun through with the tentacles of this place.”

This article was first published in HOME New Zealand. Follow HOME on Instagram, Facebook and sign up to the monthly email for more great architecture.

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Jackie Meiring.