Designed by award winning architects Lance and Nicola Herbst, this Piha holiday home floats among the pōhutukawa. At once elemental and polished, it’s a striking response to a difficult site

[jwp-video n=”1″]

As you drive along Marine Parade at North Piha to our Home of the Year 2018, designed by Lance and Nicola Herbst of Herbst Architects, you notice two things. Firstly the trees: ancient pōhutukawa, their massive boughs twisted and gnarled, carpet the hills and fringe the road. Then you notice the houses, perched among the trees, climbing for the view – and in just about every case, there’s a deck on the front, cantilevered up on poles, high above the ground.

It’s understandable. New Zealanders like decks. We like to stand on them with a glass of wine in hand, to contemplate the view. We like to cook on them, gather on them with friends in summer, and we like to sit on them until late at night. The thing about decks, though – and even more so on this blustery stretch of west coast, where the south-westerly can blow in cold and strong – is that they’re exposed. Half the time you can’t sit on them. It rains in winter and it’s windy in summer. You want to look at the view, and you want to look at the weather as it races in off the Tasman. But you don’t always want to be in its path. It’s all the more powerful, then, that this beach house neatly reaches for the view and light, without exposing its occupants to adverse elements.

Designed as a retreat for a couple with adult children, in future it will be used on a more long-term basis. The bach that previously occupied the site was at ground level, tucked behind the house in front and overshadowed by protected trees – much of the site is a Special Ecological Area, the highest form of protection in the Auckland rule book – and it lacked both light and sun. “It was a seriously sun-challenged site, with the mountain wrapping around it, getting very steep to the east and north,” says Lance Herbst. “As the sun comes around, it’s taken up first by the mountain and then the pōhutukawa.”

Not long after buying the house, the owners approached the Herbsts, who’ve featured in these pages numerous times, mainly for beach houses and baches (many of them award-winning) on the west coast – at Muriwai, Bethells and Piha – and on the Gulf islands of Great Barrier and Waiheke. “We wanted to use someone you could just say, ‘go ahead and do what you do’, someone you could trust with a particular piece of land,” says one of the owners.

It helped, also, that the Herbsts are used to working with and preserving trees, as evidenced at ‘Under Pōhutukawa’, just down the road from this one and which won Home of the Year 2012. As its name implies, the home nestles in the centre of a grove of those iconic coastal trees. In that case, several trees were carefully moved to make way for the house, which then seemed to take on the form of trees, its structure reaching upward to echo boughs and trunks.

Here, the approach was a little different, not just because the existing footprint offered an obvious place to build. The opportunity here was to reach up into the canopy to touch the sun, light and views and, in doing so, celebrate the very forest in which the house sits.

In essence, the Herbsts’ plan was to build on stilts. Externally, the house is a gentle, understated wood-and-glass building on six elegant steel poles and a central concrete-block box with a stone-floor entry.

A steel spiral staircase leads to the second level and sea and tree-top views. “Essentially, all the good stuff was in the upper level. With the house pushed as high as possible into the canopy, you get a view of the ocean and a tree-house feeling,” says Lance. “That not only brings in the light, but lets you engage with the canopy – and the most beautiful part of the site.”

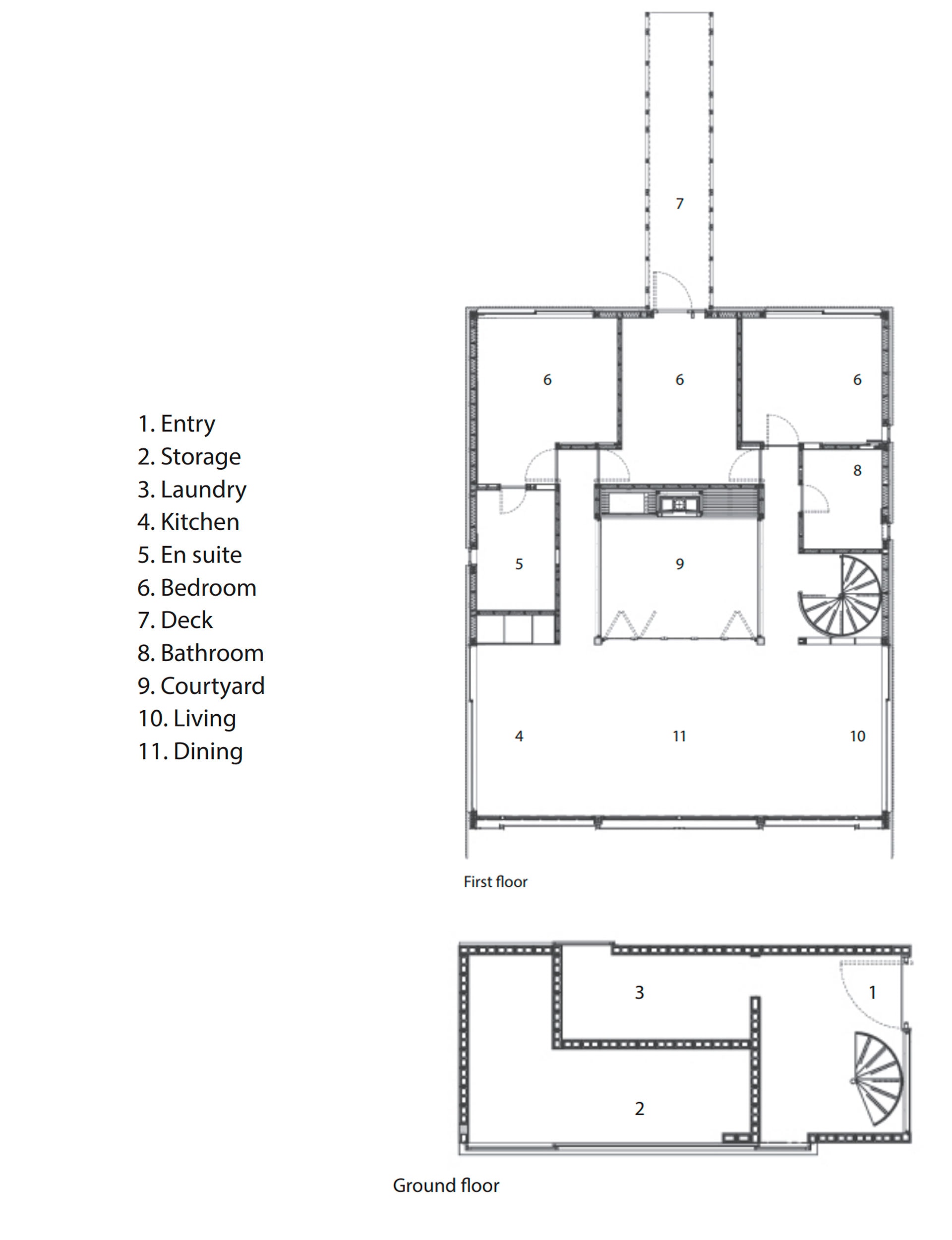

To get away from the wind, the house eventually evolved into a sort of square doughnut based around an internal courtyard, which features an outdoor fireplace. Along the front of the house, there’s a west-facing kitchen-living-dining area with floor-to-ceiling sliders. In essence, this space operates like a covered deck, complete with a chunky steel balustrade designed to allow leaning, contemplation and a drink.

Behind the courtyard, tucked against the slope and forest, are two compact bedrooms in each corner, with spectacular views into the trees; a bunk room sits between them and cleverly acts as a passageway when not in use. From here, a decked bridge leads to the hillside, which will eventually contain a spa pool. Two bathrooms, meanwhile, sit snugly between the bedrooms and main living area. It’s an exercise in technical precision, fitting rooms into a pre-determined size; when you put a house up in the air, it instantly seems bigger.

Every opportunity has been seized to bring in the light and draw attention to the tranquility and beauty of the site. Unusually, the interior plywood walls have been stained a similar dark brown to the tree boughs, while the inward sloping ceiling of light birch pulls your gaze up to a continuous clerestory window that wraps the perimeter of the house and captures the tree canopy.

“We wanted to play down the wall planes with the dark colour, making them recede into the background, into the pōhutukawa boughs,” says Lance of the move. “The fact that we’re so sheltered from the sun allowed us to do this very glassy response.”

Despite retreating inwards, the house forces its occupants to engage with the landscape in the most direct ways. In winter, storms wash in off the Tasman, rain splashes the glass and trees move in the breeze, almost like kelp. When we visited on a late summer afternoon, the sun washed in, the air seemed soaked with salt and the house filled with a deafening cacophony of cicada song.

In December, the pōhutukawa burst into blowsy, vermilion bloom and fill with feeding tuis. Being there at this time must look and feel like all your Christmases have come at once. “It’s insane, the entire forest just goes off,” says Lance. “The light punches through the canopy, a canopy that goes on and on and on, so you get dark and light patches… a God-like light comes through it all.”

Words by: Margo White and Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Patrick Reynolds.

[related_articles post1=”78837″ post2=”79051″]