Determined to keep the historical facade as it was, Mark Cannata cleverly inserted a crisp new home into an old stone ruin in Sicily, without touching the exterior

Architect Mark Cannata describes the house he shares with his nine-year old daughter, Mia, as a “stone caravan”. We’re talking in the modest entrance courtyard to his little house on the edge of Modica, in Sicily’s south-east. At 50 square metres, the 18th-century home qualifies as tiny by New Zealand standards and pretty small by European. Its small windows, thick stone walls and 200-year-old grape vines are typical of the area. The house feels like it has been there forever – and by New Zealand standards, it has.

Cannata, who established his practice Zero Zero with Francis Scott in New Zealand in 2013, moved to Modica and opened a branch there in 2015. Modica and Auckland are on the same latitude – 36 degrees and 51 minutes – but the pace here is worlds apart. Quality of life is important to Cannata, who returned to the town where his English mother and Italian father live, to raise Mia. His studio, on the town’s main street, is a mere 15-minute walk down the hill. Despite a slower pace of life, the architect’s Kiwi can-do attitude has stuck and an Italian colleague recently commented that Cannata’s practice has produced more work in three years than most local studios achieve in 10.

Zero Zero specialises in projects involving interventions within historic contexts and natural heritage. With his own renovation of a ruin – abandoned for 50 years – Cannata was adamant the exterior wouldn’t be altered, which forced him to design the interior Tetris-style. Indeed, the facade gives nothing away to the transformation within – a seemingly simple result that highlights Cannata’s experience in the sensitive restoration of historic buildings. He references boat building in New Zealand – an approach that combines history and technology – and there are similarities in his design process.

[quote title=”Cannata was adamant the exterior wouldn’t be altered, ” green=”true” text=”which forced him to design the interior Tetris-style.” marks=”true”]

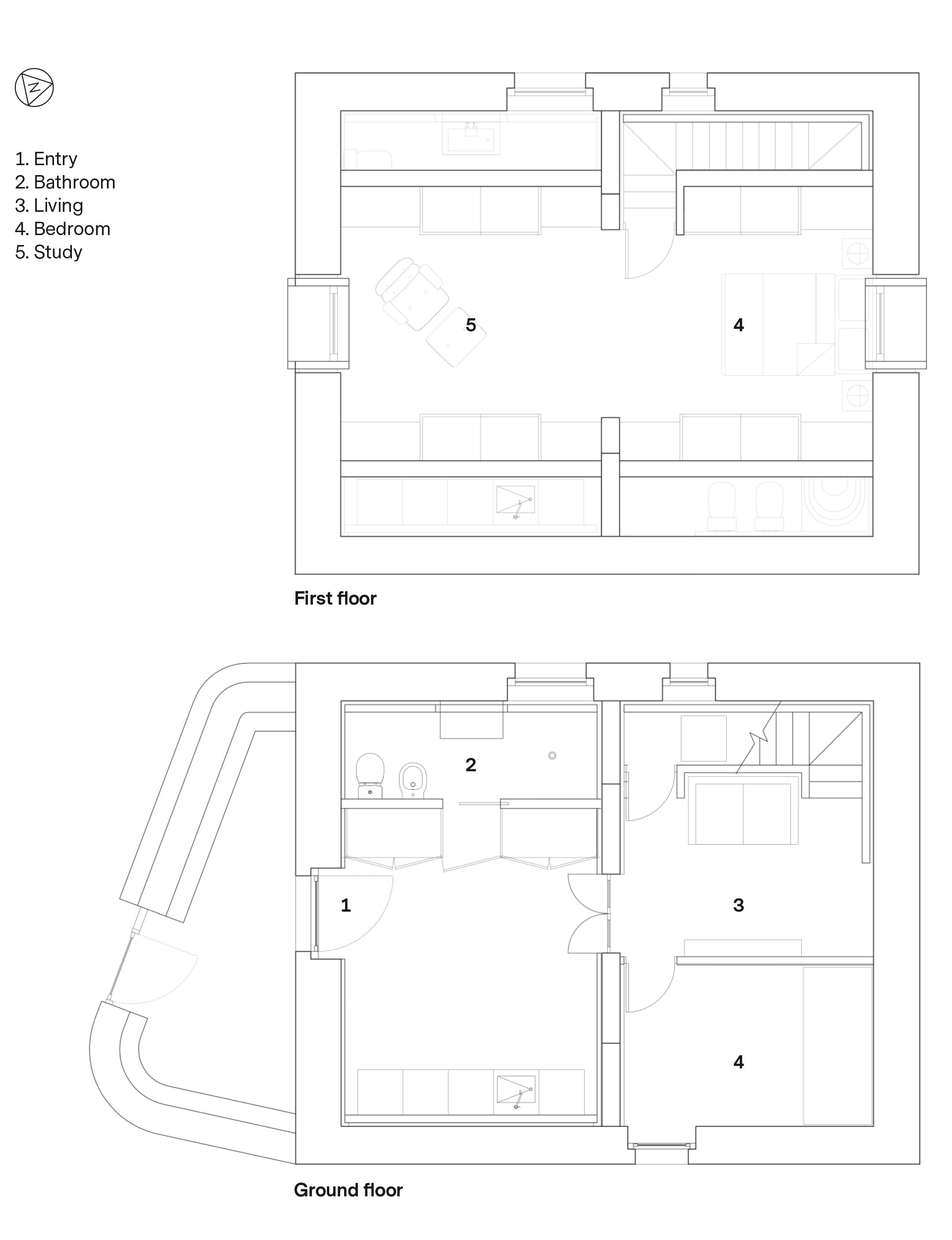

Cannata has intervened as little as possible with the original interior walls. The addition of a second level – a box slotted into the structure – is a ring beam that serves as seismic strengthening, essential in an area prone to earthquakes. The stone interior walls have been left as a feature, which makes for interesting angles and volume changes. They’ve been supplemented by board-formed concrete walls and a staircase leading up to the main bedroom.

I’m reminded of Carlo Scarpa’s museum interventions – in the way these new walls and partitions are consciously marked as additions. In fact, Cannata’s architectural thesis explored the links between Japan and Scarpa’s work.

The stone caravan idea can be read in the home’s entrance, which opens into the kitchen – a 3 x 3.3 metre space that’s modest but generous, with all its proportions just so. This lower level includes Mia’s bedroom, a petite living room and bathroom. Clever storage niches, hidden openings and custom furniture carry on the caravan concept. Upstairs, custom-made wardrobes are based on child-sized Ikea units. A concealed door from the kitchen opens into the bathroom, which is full height at 4.5 metres – a generous small room. It was originally the kitchen and black marks from the stove have been left visible, like a plume of smoke rising up the wall.

Cannata’s interventions are as close to zero carbon emissions as possible, with Near Zero Energy Building (NZEB) status. Heating is electric and mostly under floor, with a back-up heat pump used only a few months of the year. The lighting is all low-emission LED. Solar panels heat the water, which can get up to 80 degrees in summer. Photovoltaic panels will come later in the year. Water comes from a pyramidal cistern which dates to when the house was built. This supply is topped up with an artesian well shared with Cannata’s parents’ house. They’ll soon be independent and off-grid – their own “private little kingdom”.

[quote title=”Limestone, or ‘Modica’ stone,

is used throughout the town,” green=”true” text=”in buildings and walls – it’s the first thing you notice on arrival.” marks=”true”]

Outside, the only hints of modernity are laser-cut steel gates and new dry-stone walls in front of the property. Limestone or ‘Modica stone’ is used throughout the town, in buildings and walls – it’s the first thing you notice on arrival. Warm and soft, the stone turns pink in the evening light, a contrast to the dark volcanic stone of nearby Catania.

Caves are also distinctive to the town. Originally used as bronze-age burial tombs, they were adapted in the 8th century as dwellings. Cannata tells me that in medieval times 15,000 people lived in caves. Even now, about half the houses in the centre of Modica have caves. Cannata’s house is built on one that would have originally been the stables. Mia has designs on this space a future party room.

There are two other buildings on the property that Cannata will develop in stages – at which point, the first small house will become a master bedroom and bathroom for the larger home. His motivation to get cracking with phase two? To create a space for his enormous ‘Delfi’ table by Carlo Scarpa.

[gallery_link num_photos=”18″ media=”http://www.homestolove.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/MarkCannata_SicilyHome_HOMEAug-Sep19_Stone2.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/old-stone-ruin-sicily-unexpected-interior” title=”See more of the Sicily home here”]

A few years ago, while browsing through an antique shop in Catania, he found an interesting marble table top. He then spotted a monolithic Carrara marble base and realised he was, in fact, looking at the ‘Delfi’ table – a revision of a 1930s rationalist table by Marcel Breuer, which Scarpa worked on in 1968 and changed with Breuer’s help. Cannata purchased it for a song, and it took a year to get it back to Sicily. They’ll welcome the day they sit around it in the finished house: in the mean time, they’re perfectly happy in their stone caravan.

Words & Photography by: Mary Gaudin.