Maggie Hubert reviews a new book by Bridget Hackshaw that highlights a critical collaboration between three men, beginning in the 1960s and resulting in an enduring legacy.

This is a meticulously crafted chronicle describing a symbiotic relationship between art and architecture through the collaboration of three men over 14 years (1965–1979). It connects three critical figures, not formerly isolated per se but mainly existing in one another’s footnotes at a seminal time in New Zealand’s design history; a period when our national identity was still emerging.

The collaboration began when an architect and an artist with a “great affinity for Catholic symbolism” joined forces to design a chapel; so began a key and enduring relationship.

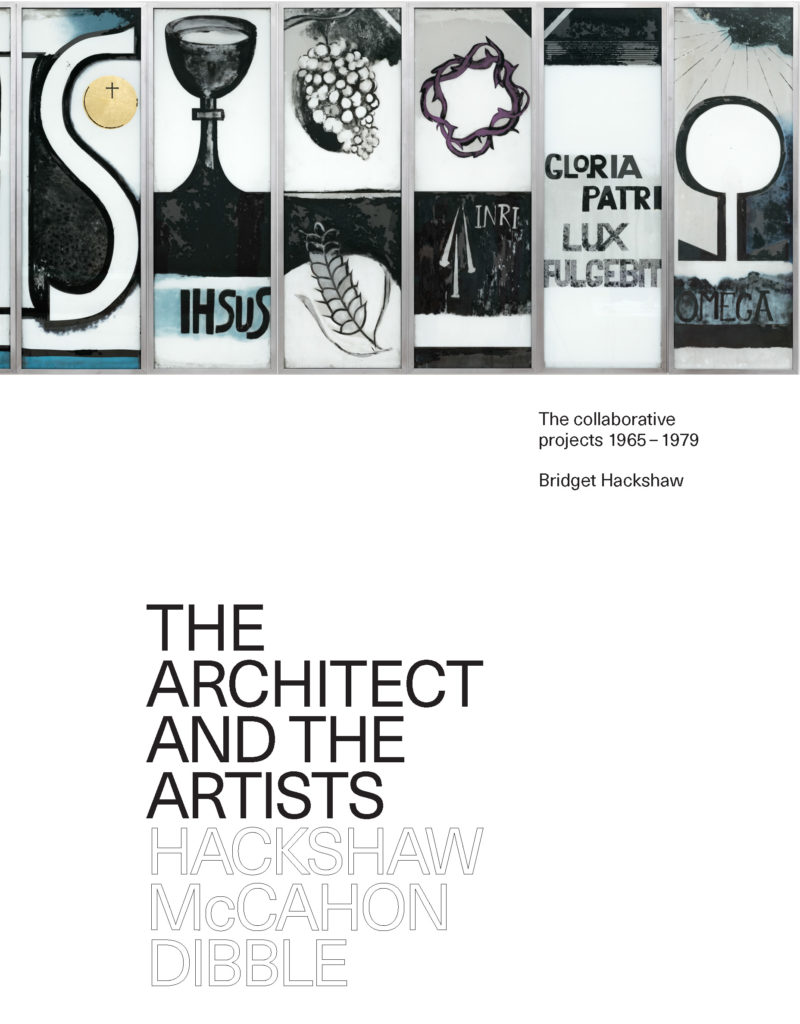

The architect and the artists of the title were James Hackshaw, a founding member of Group Architects (1951), artist Colin McCahon, and sculptor Paul Dibble. Hackshaw’s daughter, Bridget, mined the men’s individual archives, collated her findings, and, with a series of vivid, expert essays, explores this uniquely enduring relationship.

The book presents a striking collection of drawings, photographs, and handwritten correspondence, leaving us to consider the past, present, and future collaborations in art and architecture in Aotearoa.

The clean lines of international modernism were on the rise. Aotearoa was not immune to its influence and in parallel was establishing a new creative national identity. Group Architects, associated with the rise of regional modernism, looked to Māori for local precedents, reacted against the state house in responding specifically to local climates, and aspired to create humble, affordable housing for the everyday New Zealander.

Following this foundational exercise with Group Architects, James Hackshaw set up practice on his own in 1958.

The first of the 12 collaborative projects, which included churches, schools, and private homes, was a chapel for the Sisters of the Mission on Upland Road, Remuera in 1964. Just home from Vatican II, Bishop Delargey commissioned Hackshaw, a close friend, to design the chapel. The relatively progressive and relaxed changes sanctioned by the Church aligned with architecture’s prevailing humble mood. Hackshaw enlisted painter Colin McCahon for the job. McCahon recommended his student, Paul Dibble, to cast the sculptural elements. McCahon drew from the local for theological depictions, looking to Muriwai and the Auckland hills, and Rangitoto appears on Dibble’s tabernacle at St Francis de Sales Church in Torbay.

The contributions of the painter and the sculptor were integral to Hackshaw’s architecture. Unless wholly intact, space with the powerful bronze sculpture, coloured light onto rough-sawn timber, it did not sufficiently function. The power of the architect’s and artists’ work was overwhelming. A resident at the Upland Road convent, Sister Maria J. Park, was so moved she described “a soaring place of prayer that rose above the building” with the enduring “punch and guts” of McCahon’s Way of the Cross, and she included a tribute to Dibble’s sculpture in her final vows scroll.

In 1976, Colin McCahon said, “Good glass holds your hands up high and a certain glory filters through your fingers.” This emotional observation demonstrates the spatial experience these collaborations achieved, which are so beautifully portrayed in The Architect and The Artists.

Words Maggie Hubert

Images Images extracted from The Architect and the Artists: Hackshaw, McCahon, Dibble by Bridget Hackshaw. Published by Massey University Press, RRP: $65.00.