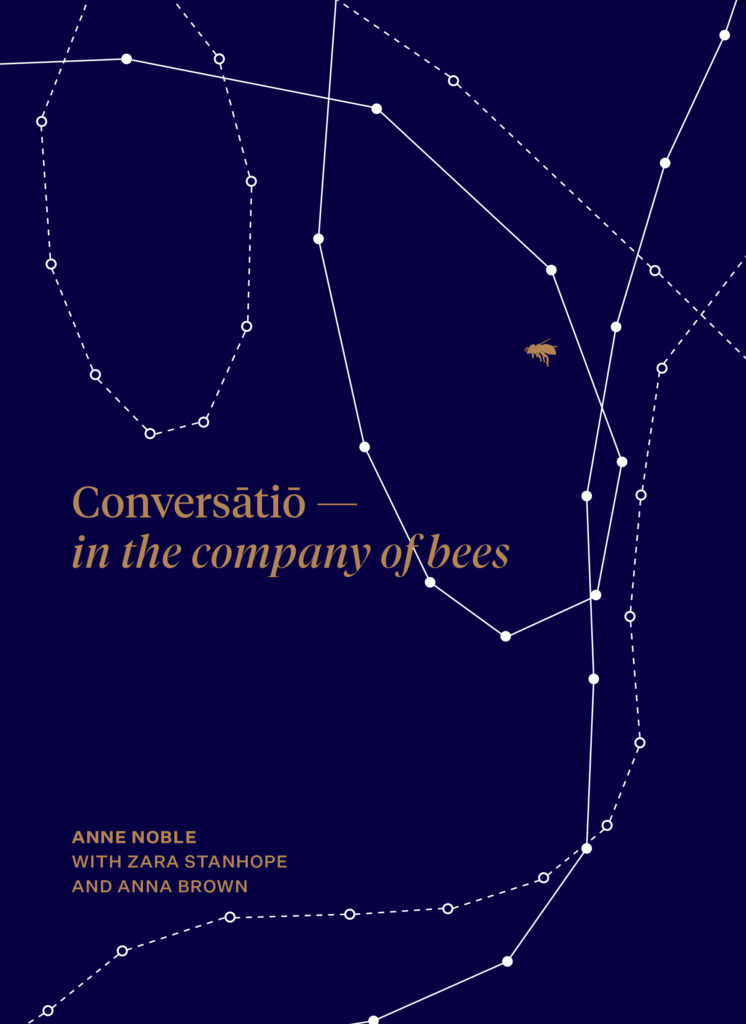

At the heart of photographer Anne Noble’s exhibition Conversātiō at Queensland Art Gallery, and her upcoming book of the same name, is a cabinet where a colony of bees lived during the duration of the show. HOME caught up with Anne to talk about the curious cabinet and what, if anything, this architecture for bees might say about designing for humans.

HOME: You collaborated with a physicist, Wellington-based cabinetmaker Sebastian Bissinger, a biological/aeronautical scientist, and others to create a temporary hive inside an art gallery. How did each of those collaborators influence the resulting ‘home’ for bees?

Anne Noble: Creating a healthy viable home for bees inside the cabinet meant drawing on the knowledge and skills of many people. For example, I worked with a German cabinetmaker to finesse the design and we chose the finest rosewood and untreated plywood for the interior cabinetry knowing that wood is a most desired material for a colony of bees.

The greatest challenge was devising the perspex entrance tunnel that would go through the wall of the building and link the gallery to the outside world. I wanted the gallery visitor to see the bees fly into the gallery through a gilded frame and then along the tunnel, casting moving shadows on the gallery wall before landing on a gilded platform and disappearing inside the cabinet. I needed help to achieve this as I learnt that when bees fly into a clear perspex tunnel they become disoriented and would crash-land at the entrance then walk home rather than fly. I learnt from a robotics engineer that bees need optic flow, that they see and navigate by reading shifts in shape and contrast as they fly. If there were no image or contrasting tones in view while they flew along the tunnel the bees would have no means to navigate.

I had the very great pleasure of working with a wonderful bee scientist from the Queensland Brain Institute, Mandyam Srinivasan, whose remarkable research into bee vision, perception, and navigation has led to the development of pilotless aircraft. We worked together to create a patterned perspex entrance for the bees, that both enabled them to fly home along the tunnel and offered a beautiful patterned form that was alive with bees coming and going as a part of the experience of this living artwork.

H: In a way you were a project manager for the construction of an apartment building for bees! How do you ‘design’ for another species?

AN: When we observe and pay attention to their preferences for a home it is easy to provide precisely for their needs. In many ways these are similar to what humans need in a house. The residence for a colony of bees needs to be dry, warm, and well ventilated, and have enough room for the colony to expand, a secure defendable entrance, and ready access to water, pollen, and nectar. Other factors that influenced the design of our cabinet included the bees’ need for ‘beespace’. We had to work out the space between the glass and the comb so there is exactly enough room for the bees to move about freely. If this cavity was too big the bees would then fill it with more wax and propolis, which would have closed off the colony from view.

H: There were also aesthetic moves, correct?

AN: Aesthetically, the cabinet references an 18th century cabinet of wonder. The red upholstered cushion serves as an insulation panel which is removed to reveal the bees on opening. Conceptually, the cabinet also references a medieval altarpiece, which, when opened, reveals an icon, which is both an object of reverence and presents an image that inspires the telling of stories. Our hope was that the cabinet would inspire both wonder and reverence while also providing the means to tell stories about the complexity of the natural world and the impacts of our disconnection from it.