This majestic ‘farmhouse’ designed by Andrew Patterson and his team on Annandale, a sheep and cattle station of approximately 4000 acres with more than 10 kilometres of coastline on the northern side of Banks Peninsula, will leave you breathless

He has lived abroad for 35 years, but Mark Palmer never lost his connection with New Zealand. He grew up on a farm in the Bay of Plenty but left the country in his early twenties for the United States, where he eventually built a successful property company, married and raised six children. But the lure of farming never left him, and this urge to return to the land led to his purchase of Annandale, a sheep and cattle station of approximately 4,000 acres with more than 10 kilometres of coastline on the northern side of Banks Peninsula.

Palmer currently lives on the farm (which is run by a farm manager) as well as in the US. Since he purchased Annandale, he has carefully renovated the farm’s original homestead and brought its magnificent gardens back to life. He has also overseen the restoration of a shepherd’s cottage on the remote northern reaches of the farm, a half-hour’s drive along a four-wheel drive track from the homestead. The farm itself is now functioning efficiently and is fully stocked. He has planted thousands of native trees.

You would think that would be a logical place to pause, but Palmer hasn’t finished yet. On the farm’s northern extremity, about 10 minutes’ drive further on from the shepherd’s cottage, work was recently completed on two new buildings, including an all-new farmhouse that pays elegant homage to its gorgeous setting. Palmer had already been working with architect Andrew Patterson and the team at Pattersons on the restoration of the homestead and shepherd’s cottage, and it was them that he asked to come up with a design for this isolated bay. The home was a finalist in our Home of the Year 2014.

The brief was loose, leaving Patterson to fret, for a while, over what might be an appropriate form for this starkly beautiful location. Patterson is well-known for creating some of the country’s best contemporary buildings – including Auckland’s Site Three, the Hills Clubhouse at Michael Hill’s golf course near Arrowtown, and the new visitor centre in the Christchurch Botanic Gardens – but a strong vein of classicism also runs through his work.

Here in this valley on Banks Peninsula, he resisted the temptation to do something ultra-modern. “I laboured very hard about whether to do a completely abstracted form on that site,” Patterson says, “and I didn’t want to do that because that bay is eternal, and one thing that you do know is it’s likely to be a farm for a long time. If you pick a contemporary form, you fight the timeless nature of the bay. But the building is reasonably abstracted in a material sense – everything about it is still very contemporary.”

Curiously enough, Patterson grew up near another Annandale Station, this one in the Waikato, which boasted an 1892 rendition of an English country house owned by the parents of one of his high school friends (and now listed as a Historic Place Category One building by the Historic Places Trust). Patterson remembers the house, with its simple verandah, as “not being excessive in any way,” and sought to emulate that and the “oilskins, gumboots and gun racks” authenticity of the place here on Banks Peninsula.

The symmetry of the bay made siting the building at its centre seem logical, and the first glimpses of it, as you descend a rugged four-wheel-drive track from a ridge line, are breathtaking. Its cedar skin, which wraps the exterior walls and the roof, has the same honeyed tones as the parched grass that surrounds it. Its simple forms appear to rest in absolute harmony with the arresting landscape. The house occupies its site confidently without ever appearing to need to compete with it. The arrangement of forms is completely inviting: you want to get down that track and see what it’s like inside.

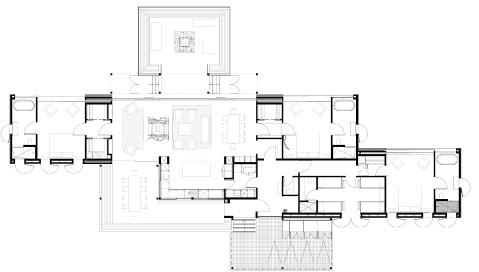

The building runs east to west, but instead of a single extruded elevation, it features two connected gabled forms which almost appear to be slipping past one another. The entrance is located in the area where these forms connect, where a lovely waft of the home’s macrocarpa linings is apparent as soon as the door is opened. A tall, thin hallway to the right leads to a bunkroom and a bedroom, while a high door to the left opens into what can only be called a great room: a long, lofty space with, at its heart, a fireplace and chimney made of stone from the farm’s own quarry.

The gabled roof is expressed inside in the way the macrocarpa linings rise to a peak, while big doors reveal a view over the deck outside and across the field to the rocky beach. The large, practical kitchen looks onto another, south-facing deck protected from breezes coming off the water. Each of the three main bedrooms has its own simple bathroom and a view towards the sea. The house feels as if it is a million miles from anywhere.

Palmer envisages the home as a place for the family to stay when they’re visiting and also as a luxury holiday rental property to be included in Annandale’s coastal farm escape and luxury villa collection. You can see why he appears so proud of the place, as it is easy to imagine it being somewhere that guests would never want to leave, a home with a wonderful sense of calm in an isolated bay perfectly in tune with its marvellous surroundings. –Jeremy Hansen

Q&A with architect Andrew Patterson.

HOME How did this project come about?

Andrew Patterson Mark rang out of the blue and said [the farm’s original] farmhouse needed altering. It was terribly dilapidated, but it had this beautiful garden. Once we had done that, he started to formulate what he wanted from the rest of the property, which included this new building. He had no specific architectural vision other than to create experiences that built on the experience of the farm.

HOME How did you decide what was appropriate in this bay?

Andrew Patterson The bay was rural and peaceful and rugged. I laboured very hard about whether to do a completely abstracted form on that site and I didn’t want to do that because that bay is eternal, and one thing that you do know is it’s likely to be a farm for a long time. If you pick a contemporary form, you fight the timeless nature of the bay. But the building is reasonably abstracted in a material sense – everything about it is still very contemporary but unmistakably rural New Zealand. It’s not excessive in any way. It has classic proportions and natural forms. The drama of that house is its centredness in the amphitheatre of the bay.

Photography by: Simon Devitt.