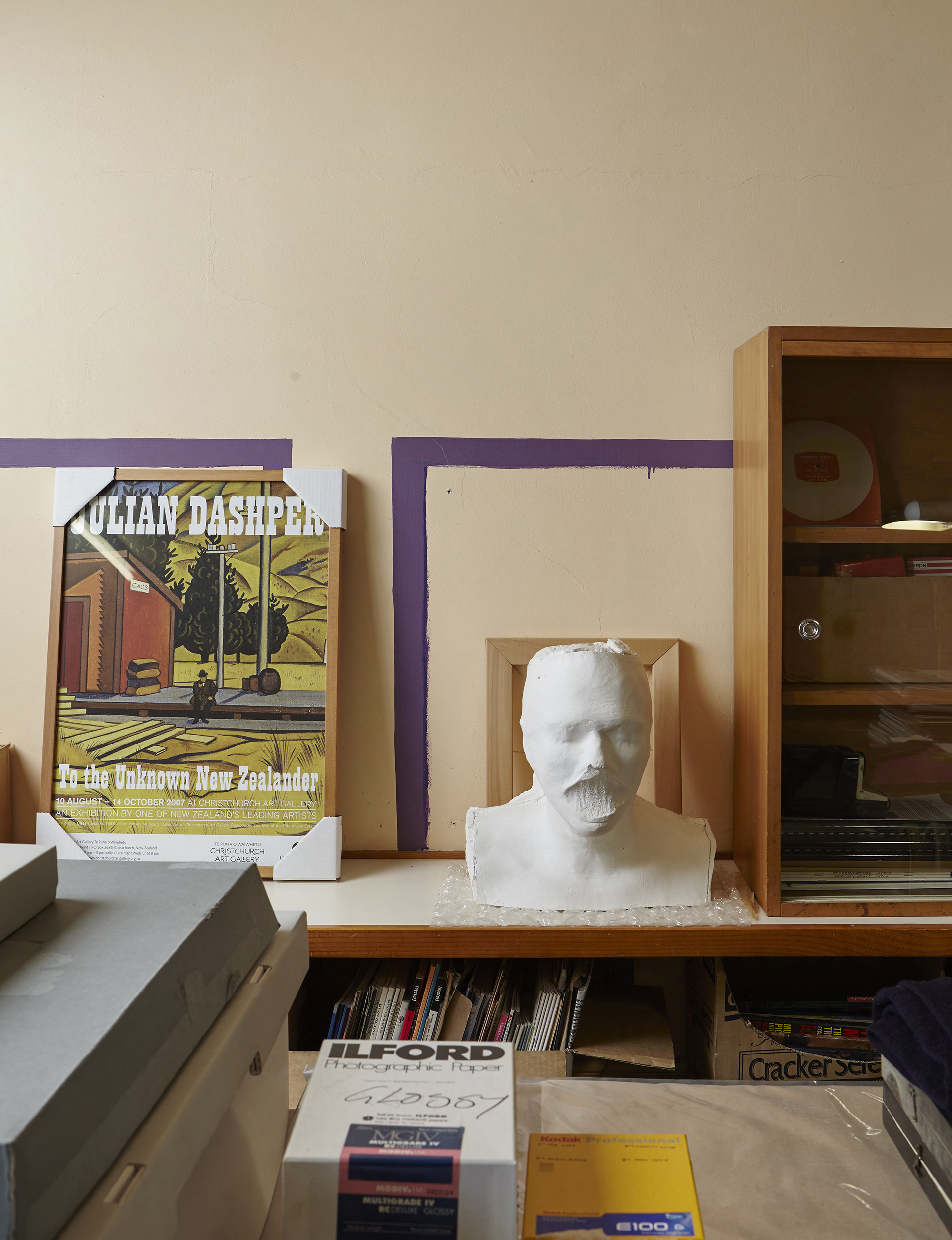

The late Julian Dashper’s fascinating Auckland studio, with its neat arrangements of art and ephemera, remains just as he left it when he died in 2009. Story Words by Mark Kirby

I was moved when I first saw these photographs of my friend Julian Dashper’s suburban west Auckland studio. Julian, an acclaimed artist, died in 2009, but his partner, Marie Shannon, has changed little about the studio since. The immaculate arrangements of objects on tables are exactly as Julian left them. It looks as if he has just popped out for a moment.

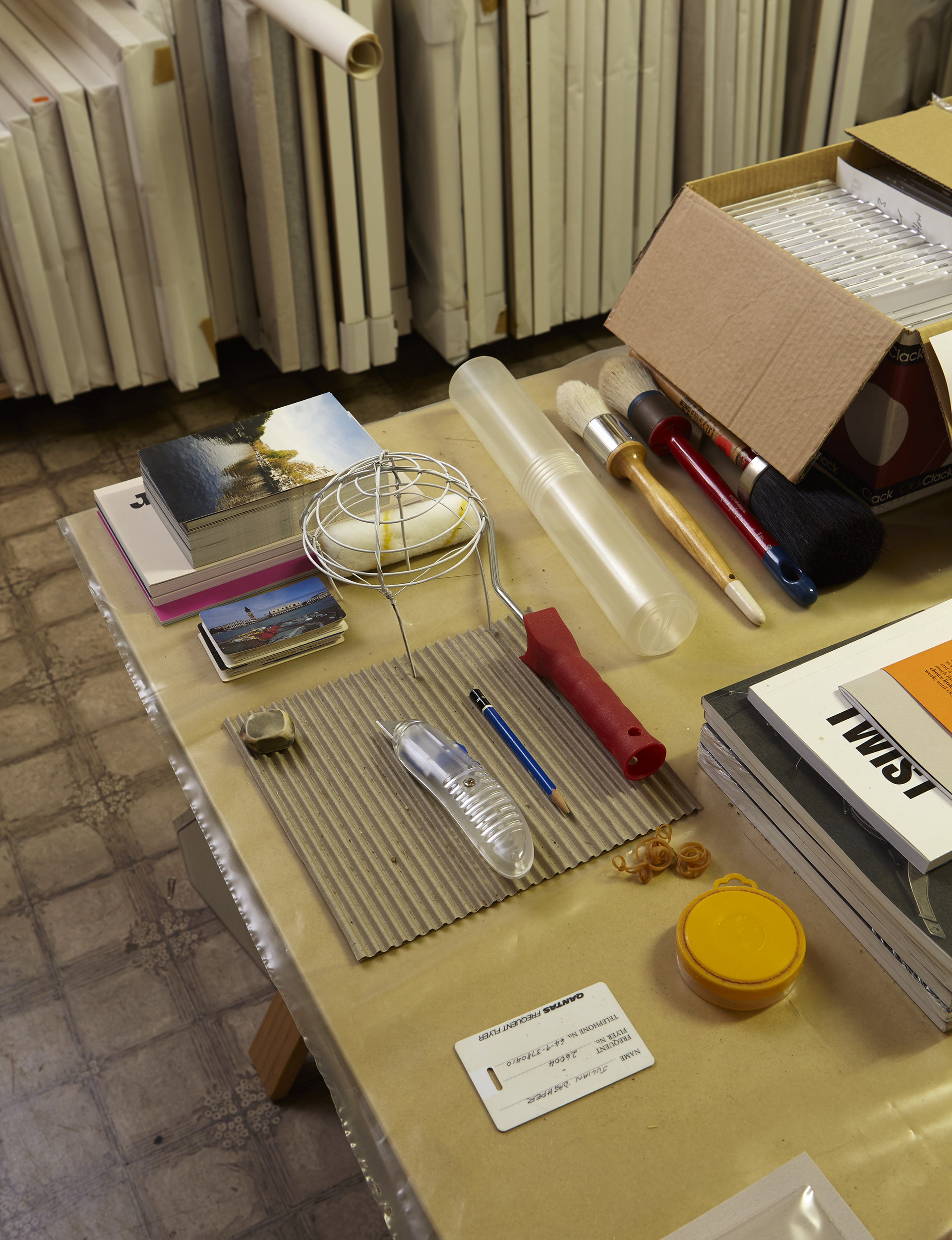

Marie, who shared the studio with Julian, says his process of arranging things on tables began gradually, as his practice developed and he increasingly had works made by fabricators, or used existing, manufactured objects. The arrangements were a combination of functional objects and materials, such as the pencils and notepads, and things he might be considering as potential art works, such as stacks of flat paint brushes or musical triangles in descending sizes. “He might place some of his own small art works that he was thinking about, or considering in a new context. Therefore his studio time was thinking time, and time to look at objects and shapes in relation to each other,” Marie says.

I knew this building long before Julian moved there. When I was young it was my local post office. My mother used to buy things there: wool, presents for us kids, and our school stationery. I remember buying a toy boat there once. The women who worked in that shop knew my family by name. Then it became a hair salon. Over time this shop and the neighbouring butcher, green grocer and supermarket closed; eventually, in 1998, Julian made it his studio. He and I used to discuss this weird coincidence when I visited him there, surrounded by artworks, books and archives. The conflation of my memories as a child with those of Julian and this studio makes viewing these photographs particularly poignant for me.

Julian liked to say that he was an international artist working out of New Zealand. He insisted that didn’t have to be located in the mainstream centres of Western art, like New York or Europe (and, these days, Asia), to be at the centre of contemporary practice. It was interesting how he so effectively acted out this form of internationalism from a modest suburban Auckland studio.

While the notion of ‘centre’ these days has become dispersed, in large part due to the influences of contemporary media, for some time Julian’s eccentric approach to internationalism made him unique in New Zealand art. He seemed to have a higher profile everywhere other than New Zealand. He wasn’t fashionable here, even though his reputation extended across Europe, the UK, USA and Australia. Julian didn’t mind this conundrum, as it sharpened his critique of New Zealand art and the introspective nature of a lot of contemporary New Zealand culture, which he thought was overtly nationalistic. Julian refused to work according to the traditional regionalist paradigms of New Zealand art. You can see clues to this in his work and references to the many artists he admired.

Because of this, Julian was sometimes misunderstood in his homeland. The hard-edged internationalism and intellectualism of his work was too clever for some, and he was considered too smug by far. Julian didn’t mind this. In fact, he considered criticism such as this to be part of his work, and embedded it into his practice: he once republished the complete set of negative reviews from a New Zealand Herald critic in the catalogue-cum-artwork Reviews… he loves me not (2002).

Julian sometimes preferred to make New Zealand art one of the core subjects of his artwork. His unique form of regionalism came through strongly in ‘The Big Bang Theory’ (1992), a series of five full-size drum kits emblazoned with the names of canonical modernist New Zealand painters: Colin McCahon, Don Driver, Rita Angus, Ralph Hotere and Toss Woollaston. His Darwinian homage to these artists is now recognised as a significant moment in New Zealand art history, and part of the canon of late 20th-century New Zealand art.

The fastidiousness of Julian’s studio is reflective of how he meticulously choreographed where and when his work was shown. This was most obvious in 1992 when he ‘exhibited’ an advertisement he placed in Artforum International. Most people were astute enough to recognise the fundamental cleverness of his intervention and its critique of how context – in this case, being included in an important critical magazine – imbues artistic credibility. In this case the artwork was not so much the image Julian had placed in Artforum, but the chatter that it stimulated.

‘Untitled (The Warriors)’ (1998) worked in a similar way when first shown at the time of the Sydney Biennale. This small-scale, almost toy-like drum kit offered a metaphor for New Zealand identity: a shy, uncertain and self-consciously small-framed child trying to be heard among the bigger boys of international art. No ‘big bang’ here. The evident humour, as well as the cultural cringe it implied, was indicative of Julian’s rigour and unwillingness to suffer fools caught up within nationalistic theories of art and culture. The references in this work to the Warriors rugby league team (of which Julian was an avid fan), perhaps the most working-class of all sports, were as much a critique of art’s pretentiousness as an assertion of the rich connections between cultural activities distanced only by class.

Julian’s drum-based works, such as ‘Untitled (The Warriors)’ and ‘The Big Bang Theory’, were indicative of an ongoing conversation with popular music in his artwork. This most clearly came through in a plethora of recorded performances, produced as polycarbonate records, which he would display on the wall in the manner of abstract paintings. The recordings were often of events or performances held within his exhibitions. In ‘Blue Circles #1-#8’ (2002-03) Julian displayed eight beautifully transparent polycarbonate LP recordings of incidental noise captured in front of Jackson Pollock’s 1952 icon of modernist painting, ‘Blue Poles [Number 11]’, which had been purchased in some clamour and controversy by the National Gallery of Australia in 1973.

In a similar way, in several series, Julian inverted the relationship between painting and photography, at one time reproducing multiple painted portraits of a single unique photograph. In these works the multiple paintings are indistinguishable, making it impossible to privilege one as more unique than any other. He also played with reproduction and originality in ‘Untitled Slides’ (1991) where he displayed, in the manner of painting, a series of slide sheets containing images of original art works. The beautiful gridded symmetry of these works was a deliberate reference to the geometric abstraction of 20th-century modernism, particularly minimalist art, in which Julian was particularly interested.

Julian also conflated abstract and realist art. In fact he argued that abstract art could never be abstract, and that all art represented something. What is always ‘represented’ in art, of course, are the contexts and values of art itself. Abstract art was a primary subject of representation for Julian. He said he ‘made’ abstract art, as tradesman might craft a chair, and that what he made was abstract art because it looked like abstract art.

I have written previously that Julian’s art work is as beautiful to think about as it is to look at. His position was that art should be both visually and intellectually interesting. Julian was interested in aesthetics as a subject, and would often play with the notion of beauty. This is perhaps most evident in his ‘Untitled’ (1996) series of paintings on drumheads. These beautiful circles of colour, which mimic Jasper Johns, Kenneth Noland and other mid-20th century abstract artists, saw Julian receive much acclaim as a colourist. However, it was not Julian but Leo, his toddler son, who had selected the colours for each painting. Here, irony, humour and intellect are conflated with elegance and beauty. And here, in this work and these photographs of his fascinating studio, is where you can find the essence and richness of the art of my late good friend.

Words by: Mark Kirby. Photography by: Toaki Okano.