Light and space for a Brooklyn artist

To wake up surrounded by your own work would be, for many, the surprise twist in the plot of a particularly bad dream. But for artist Jennifer Bartlett – famous for her monumental installations of painted square steel plates – it’s simply a way of life.

The general assumption is that the corollary of success is a separation of home and studio; that artists will inevitably leave the loft spaces they’ve cobbled together inside unused commercial buildings in favour of comfort – think a detached house with a front door and garden.

The home and studio New Zealand-born, New York-based architect David Berridge designed for Bartlett in the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Clinton Hill certainly has the garden and the front door (though with a height of three metres, it’s hardly your average entryway), but the rest of the former warehouse thrums to the daily rhythm of the artistic process.

Berridge – who also worked on Bartlett’s previous five-storey apartment in the West Village, her houses in the seaside town of Amagansett, Long Island, and on the Caribbean island of Nevis – says in contrast to her detailed work, built in intricate sequences of brush strokes and dabs, her home aesthetic is fairly simple. “An artist doesn’t get to work at 9am and stop working at 5pm. There’s a constant involvement with the work,” he says. “And because the building wasn’t spectacular, there wasn’t much desire on either of our parts to make it anything more than a box for the art. For me, it was more about playing off what she brought to the project, rather than trying to impose a style. Just let the building be what it is, as simply as possible, and let her art be the thing that really makes it.”

Vanderbilt Avenue, the street on which the house stands, is a mix of residential buildings and small warehouses with the sprawling Brooklyn Navy Yard port on the East River at its terminal point. The area contained many sugar and candy manufacturers, who eventually made it their trade union hall. By the time Bartlett purchased the building it had become a kindergarten and been divided up into playrooms and child-sized bathrooms.

“The ceilings had been dropped down to eight foot, with acoustic tiles and fluorescent lights,” Berridge says. “But she loved it, because of the blacktop [parking lot] that came with the property. It had three exposures, which is very unusual, so she figured it would be okay.”

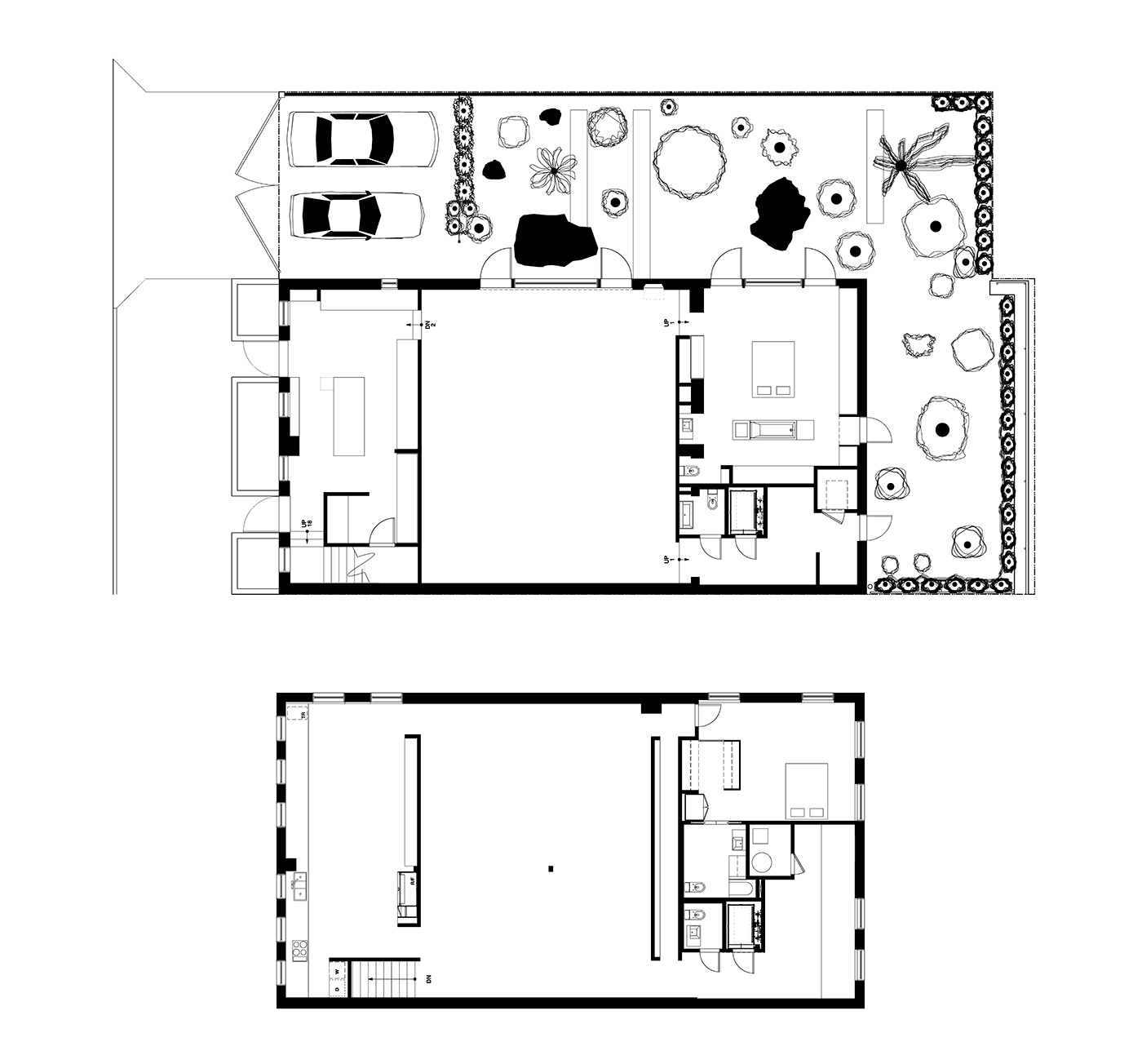

What the original building lacked in the sense of period detailing or ambitious architectural draftsmanship, it made up for with massive interior spaces, natural light and a hardy utilitarian palette of wood and raw brick. Working with these loft signatures, Berridge made the hall liveable, adding under-floor heating, a lift between the floors, bedrooms and a kitchen on the upper floor with a long bench running the entire width of the building.

“With renovations on buildings like these,” says Berridge, “you never know what you’ve got until you start doing demolition. Once we started, none of us could figure out what was holding the building up, because there were no posts.”

They eventually discovered an enormous steel beam that runs the length of the building, supported only by the front and rear walls. “It was quite something,” says Berridge. “But that’s what allowed us to have this huge open space on the ground floor.” That space is essential, because Bartlett’s works are on the generous side. One of her most famous installations, ‘Rhapsody’, is made up of 987 metal tiles that wrapped around three walls of the Museum of Modern Art’s atrium when last exhibited in 2001.

Today, a few of her works hang in the upstairs studio, each on a scale that demands the viewer back up a good few metres to see them properly. The upper level is bordered by the kitchen at one end and lit by skylights Berridge punched through the roof.

Downstairs, Bartlett’s bedroom is in a ground-floor addition that was built onto the back of the building about 50 years ago. It is adjacent and open to her painting studio, though it can be closed off with a heavy sliding bookshelf on rollers worthy of a Gothic murder mystery.

When each artwork is ready it goes upstairs for further work and viewing through an ingenious feature Berridge created when he realised the industrial staircase was too steep to move paintings easily between floors. He sliced out a three-and-a-half-metre section of floor between the joists so the oversized works can be “posted” up or down.

In the artist’s West Village apartment, she moved her bed into the swimming pool area on an upper floor, but here in Brooklyn she sleeps where she works. There are no boundaries between spaces and no living areas that are traditionally designated. Whether working alone or entertaining a crowd, the art is the focus of Bartlett’s house. It’s a salon, in the original sense of the word. “A lot of architecture is about making a statement with space, but this is exactly the opposite,” says Berridge. “It’s the architecture of the everyday. It’s not a frilly frock – it’s the blue jeans and white shirt of architecture.” –Sam Eichblatt

Q&A with New York-based architect David Berridge

HOME You’re a sailor who became an architect. What made you make the change?

David Berridge It wasn’t that I thought “I’m going to be an architect!” It was a way to get away from the boats. I got a portfolio together and got into Parsons [School of Design in New York]. Then I looked at myself and said, I know how to keep the water out of buildings, because I’ve spent more time in boat yards building boats and fixing them. I didn’t need the practical side of it, I needed the emotional side of it. [Architecture school] was the best thing I ever did. It has showed me all this other stuff. I was 35, and it just opened up a whole world for me. New Zealand has a great education system but I was the guy sitting in the back of the class being told I could only do shop. So architecture was a new thing to be exposed to, a bigger part of life.

HOME What did Jennifer bring to it that a more traditional client might not?

David Berridge Jennifer had a really strong idea of where she wanted to go. The challenge was taking that idea of wanting to take something conceptual and intellectual into three dimensions and pull it off with all the practical requirements of a building. Working with creative people is really inspiring. It pushes you to really think about what it all means. Growing up, I didn’t think I was an arty person, but you realise it is life.