A building of the South Pacific. A sculptural pavilion of asymmetry that came first. A trio of pavilions, one for living and two for sleeping, that came second. A place for contemplation; spaces for restoration.

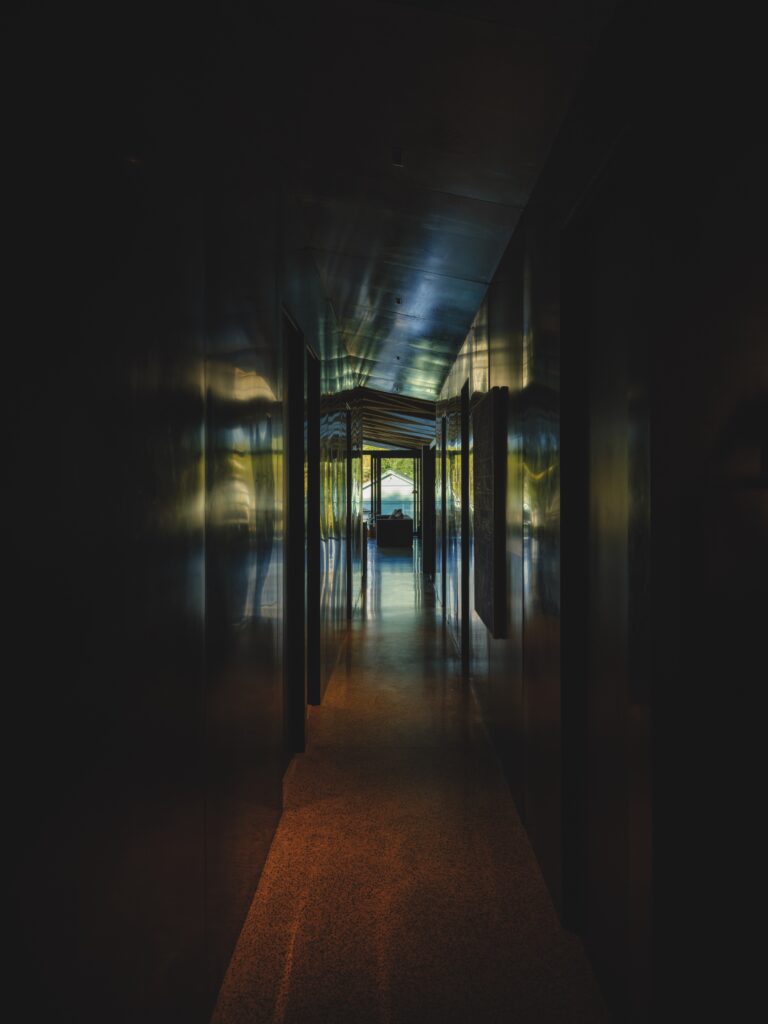

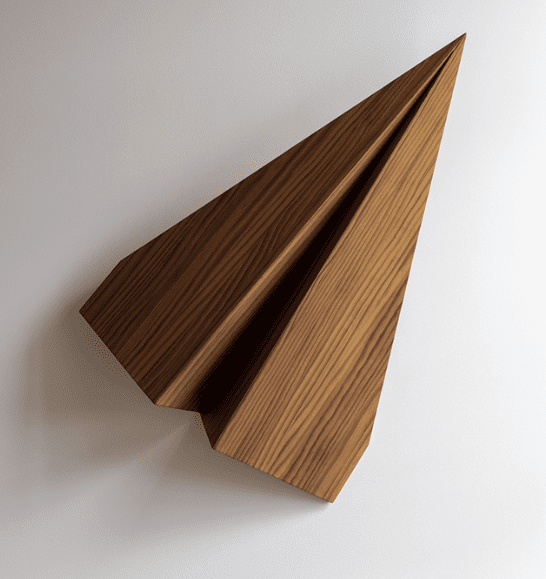

The skeletal structure of the Gateway Pavilion, an architectural folly designed by Stevens Lawson, focuses its many viewers’ gazes steadfastly on the water. The dynamic 16-metre journey through its moving form evokes a whare, a meeting house, a barn, a boat shed — it could be many things; the ideas it presents are vast, morphing as you move through it, but it’s an experience that is distinctly unified: an amalgamation of ideas that form an abstract narrative of Aotearoa’s architectural history.

First erected in 2017 and used to welcome visitors to Waiheke’s Sculpture on the Gulf at Matiatia Bay, it was later moved to its current site where it continues to invite wonder, drawing visitors into its folding arms. Perched here, high above the water, it became the starting point for a more ambitious project beside it — a powerful three-pavilion form that turns its face to the sea while its back is drawn into the undulating topography of a site that ultimately drops away to the western shoreline of Waiheke Island.

Pivoting around natural curves in the land, it too references whare, and the quintessential New Zealand barn. By separating the pavilions — two for sleeping, one for living — private, sheltered courtyards, micro gardens, are formed in the voids between.

The primary pavilion reaches skywards, a lattice timber ceiling drawing the eye up as well as out; the gabled roof extends to create a sheltered alfresco space overlooking its built muse.

Although significant in size, these pavilions sit gently in the landscape — dark roofs and natural cladding fading into the hillside. Materials were chosen to voice a distinctly New Zealand story — both structure and cladding, inside and out, are timber, a decision that offers cohesion and familiarity, while burnished concrete floors deftly tie the building to its site.

Echoing the geometric asymmetry of its counterpart, the house was conceived as a sanctuary. Mawhiti means ‘escape’, and the clarity of space within resonates wholly with its name.

“The pavilions fan out across the site, each framing an individual view of the Gulf islands,” architects Gary Lawson and Nicholas Stevens explain. “We aimed to craft a house for contemplation and retreat with a strong sense of its place in the world — a place of restoration.”

There’s a dialogue at play here: two structures, folded into the curves of the land, that speak to one another, infused with meaning and legacy, while presenting something refreshingly new.

Words: Clare Chapman

Images: Simon Devitt

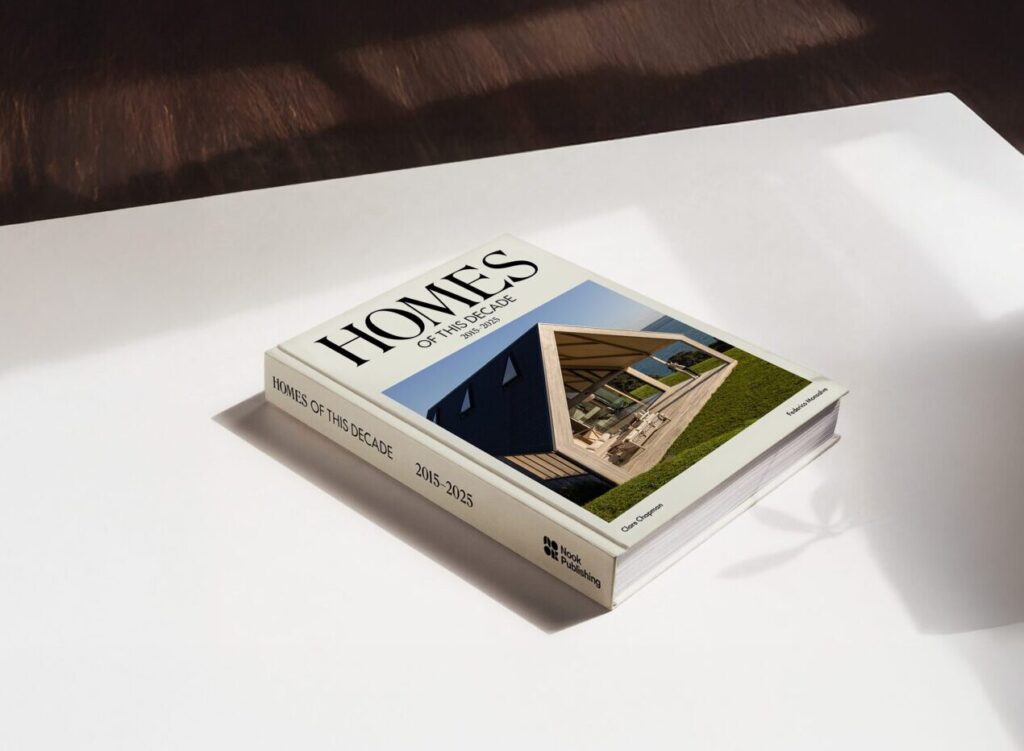

This feature first appeared in Homes of this Decade 2015-2025, which was published by Nook Publishing in 2025.