There is a strange power to the spaces that artists have occupied, the rooms in which they have crated their work. In the early 1950s, Colin McCahon’s paintings had arguably generated more hostility than praise, and he indicated that he felt his creativity had stalled: He was casting about for a way forward in his work. He left the South Island, eventually securing a curatorial job at the Auckland Art Gallery and, according to Peter Simpson’s book Colin McCahon: The Titirangi Years 1953-1959, the artist found a new optimism in the bohemian atmosphere and warm climate of his new environs. McCahon noted in a letter to Charles Brasch that Auckland felt “not mock English or Scottish but becoming NZ & possibly what one would call Pacific”.

The McCahons purchased a small bach in Auckland’s bush-clad western hills of Titirangi, and the artist embarked on a transformative period of work which would lay the foundations for the rest of his remarkable career. First, though, he set about fixing up the property, planting a vegetable garden and acquiring a dinghy. After six months he began using the little spare time he had outside his working hours to paint.

Simpson notes that McCahon stopped painting the Biblical narrative works that had dominated his earlier oeuvre and focused more intently on landscapes, which he had painted since the beginning of his career. Inspired by what he described as the “wildness and freedom of his surroundings”, McCahon began a series of works that rendered French Bay’s kauri trees and the lush, abundant greenery into fractured, abstract, energetic creations that marking a new beginning in his practice. “You may notice the lack of ‘composition’,” McCahon wrote to his friend Ron O’Reilly. “I no longer compose, but let a picture grow from a core – the movement is spiral rather than anything else.”

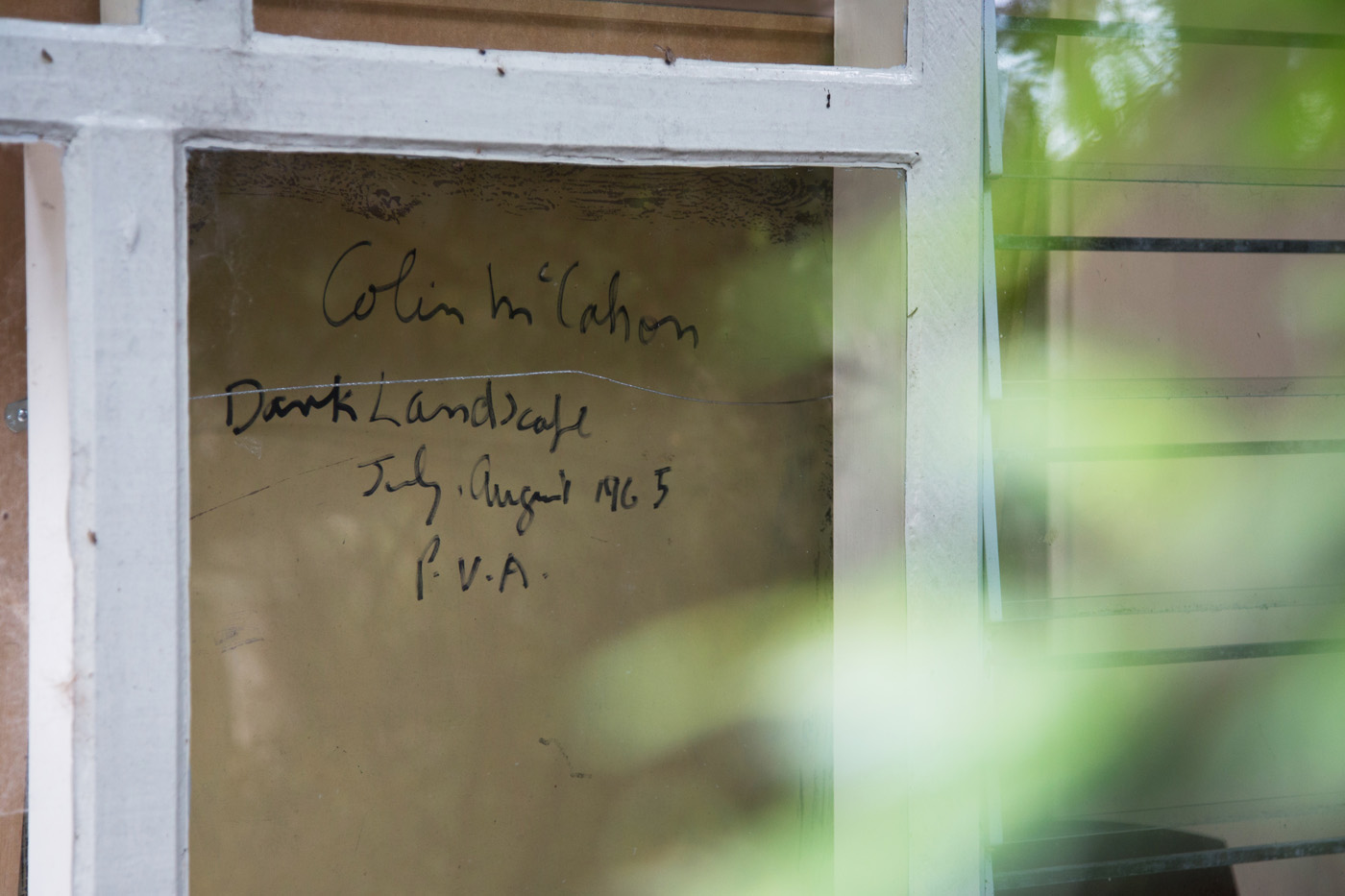

The artist, of course, could never forsee what would eventuate: that some of his works would return, for a brief period, to the house and be sold for sums he would have found surreal. In 2014, this is exactly what happened: four important McCahon works spent a weekend at the house before they were auctioned. (The home was sensitively restored in 2005 by architect Graeme Burgess, while architect Rick Pearson designed thoughtful installations that tell of the McCahon family’s life in the house. It is now managed by the McCahon House Trust and is one of Auckland’s loveliest cultural assets.)

More than 500 people came to see McCahon’s works that weekend, including folk who had known him, his wife Anne and their children when they had lived there. It is only with the benefit of hindsight that we can now appreciate how significant the period in the house was for the painter, and how important the works he created there have become in assessing his artistic progress. “The contrast between the environment in which he was born and raised and that he moved to when he purchased the house at French Bay was so massively profound that it affected his work immediately,” says Ben Plumbly, a director at Art + Object auction house, who organised the sale of the works and their weekend at the house. “As the work goes on it becomes more universal and spiritual in concern, but [in Titirangi] it was very much more concerned with environment than at any other time in McCahon’s career.”

What would McCahon have made of this event, of the sale of works like ‘Black White Landscape’, painted in 1959, for $125,000? “These things throw me a bit,” he wrote to his dealer, Peter McLeavey, about a significant sale later in his career that Jill Trevelyan recounts in her recent biography of McLeavey. “I feel kind of helpless.” In another letter, he wrote that “I’m not painting to sell but to state a message about the land and the people.”

According to Plumbly, this message was not lost. In fact, he says taking the works to the house for this short period was a reminder of the struggles of McCahon’s career, a chance to temporarily silence the distracting cacophony created by their monetary value. “When you’re caught up in the market like we are, sometimes things become so detached from their conception that you forget that they were made by a real person struggling with life and a family and money and all those things we all do from day to day,” Plumbly says. “To take them back to where they were made reminds you of the manual handicraft element of them. The house is all about that, his imprint is writ large there. The paintings, when you get down to them, are dirty old household enamel paint on bits of hardboard that were floating around, and to put them back in that house reminds you of that. They have this transcendental value that makes them worth far more than their material and monetary value. He had no interest in the market and painting to an audience and you’re reminded of that in the house.”