This modern farmhouse on the harbour at Point Wells was designed around the collections of a lifetime and the rhythms of rural life

This modern farmhouse in Point Wells celebrates subtle crafted detail

The village of Point Wells is surrounded on three sides by water, across the Whangateau Harbour from the beach-side settlement of Omaha. It’s a sleepy, estuarine place: one road in, one road out; big trees, a store and some lovely chunks of tidal waterfront land. Twenty years ago, the owners of this new house, by Aaron Paterson, Dominic Glamuzina and Steven Lloyd, reluctantly sold their old house beside the estuary and moved to Omaha – much more attractive to their teenage kids at the time. They then spent two decades working out how to get back.

When they finally made it back across the causeway, it was for a different sort of occupation: a decidedly rural one. Having retired from full-time work in Auckland, they wanted to build a house that was part retreat, part permanent home – a modern farmhouse, complete with out-buildings and lots of room for people to stay.

They planned an orchard, a cricket oval and a huge vegetable garden. It had to cope with one person in the middle of winter, or 20 in the height of summer. And it had to house a wonderful collection of art and artefacts gathered over a lifetime, including what you might call a cabinet of curiosities from around the world that takes in taxidermy, ethnic art and fertility symbols, which sit lightly next to art that includes several large works by Allan Maddox.

“They wanted a particular type of building. A gable. And that wasn’t something that we’d ever really done before,” says Paterson. The idea was a challenge for Glamuzina and Paterson, whose practice was known for darkly intelligent buildings and who, Lloyd included, have since gone on to their own practices. Through the design process, the architects came up with all sorts of ideas on how to tweak the classic rural vernacular: the owners were determined to have that gable, and in the most low-key, pared-back way possible.

The architects worked within the overall scheme to introduce beautiful details. If it was to be a gabled, shed-like building, it would be a collection of perfect shed-like buildings – contemporary in precision, if not materials. The result is deceptively rustic: pitched-roof buildings, clad in cedar weatherboards, and with tall, floor-to-ceiling casement windows.

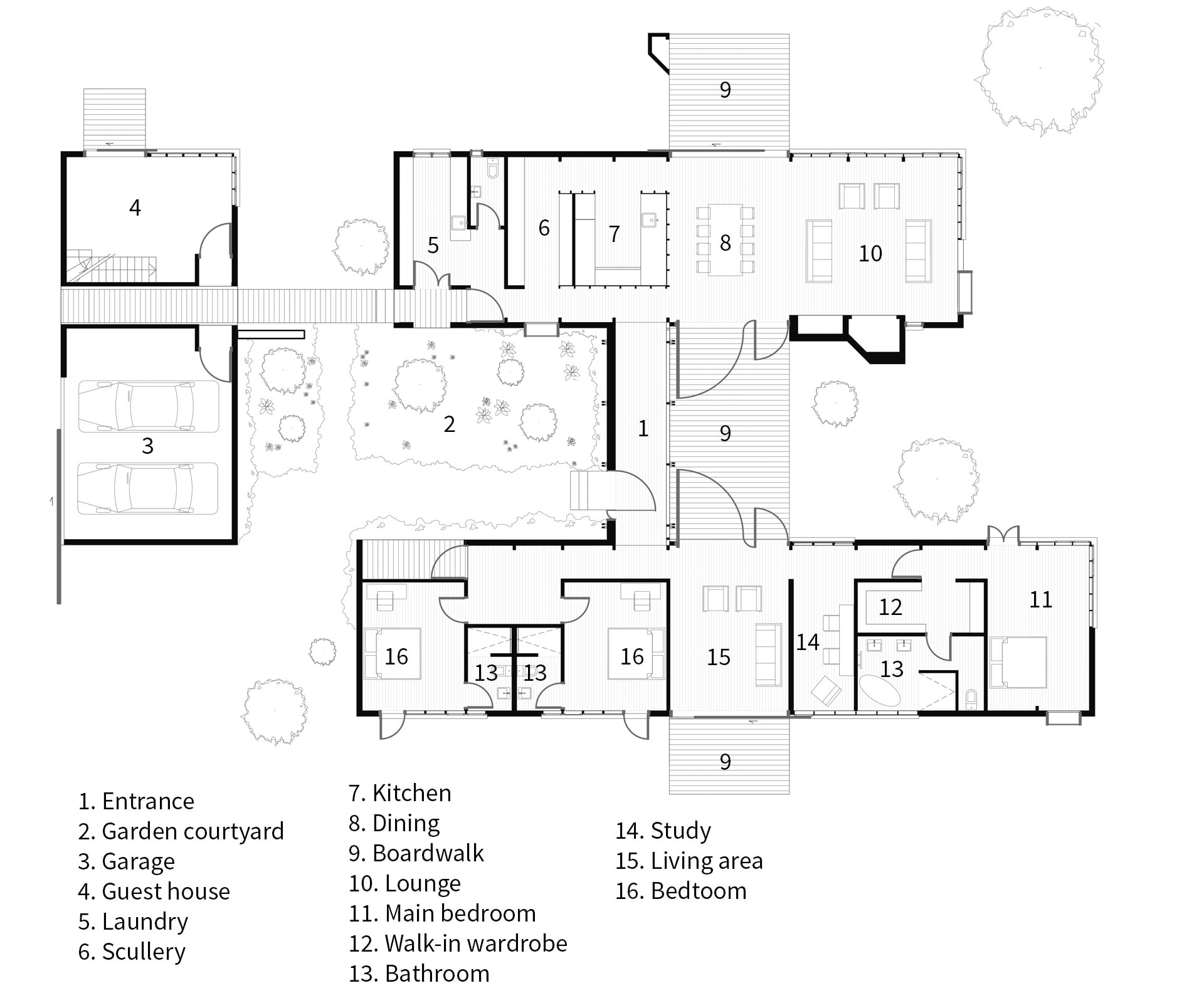

It’s a lovely spot. Down the driveway, under huge established macrocarpa and beside post-and-rail fences, past a steel shed, you pull up in front of a big pitched-roof garage, which contains a bunkroom above. You can see very little of the house behind, which is two long wings connected by a ‘boardwalk’, a layout that creates sheltered decks and courtyards between buildings. “The surface area makes lots of different spaces and walls to look at,” says Paterson, “and ways to control the wind and sun without overpowering the landscape.”

The house is raised lightly off the paddock on timber piles, in the way that farm buildings are. To access the interior, you climb poured-concrete steps, then onto oak floorboards. “It raises them up off the grass,” says Lloyd. “It gives a lightness – that shed connection. We had this idea that the planting sits the building across a green plateau.”

The two structures run north to south, connected by a ‘boardwalk’ that also contains the front entrance – though, as Paterson notes, “That’s the dramatic entrance – but it’s almost never used.” From the front door, you turn right to the ‘private areas’ – housing three bedrooms, three bathrooms and a study for the owners down the east side of the house – or left to the great room, a tall space with a high truss ceiling and massive poured-concrete fireplace that flows out to the west. In between, there’s a deck and a courtyard, which means no matter where the wind, you can always find a calm spot.

The design is both monumental and intimate, in the way that traditional small New Zealand churches are: a tall, gabled space with a skylight in the top that spills light down into the living space. This space is furnished with kilims, chunky furniture and a very large, very soft ottoman that holds the room.

“It’s just got this really pure, beautiful volume inside,” says Paterson. “It feels really right. We spent a lot of time agonising about really simple things that you wouldn’t expect. You’re not making major design changes, you’re just focussing on really subtle, crafted detail. And that was the most interesting thing about the process.”

Instead of fascia board and soffits, the corrugated aluminium reaches out over the edge of the roof; the weatherboards, meanwhile, start thin and slowly, board by board, and get deeper, until the boards at the top of the gable are almost twice the size. The angle of the roof is exactly 45 degrees, which lends precise geometry: as you go out a metre, the roof goes up a metre, so the two buildings are long and reasonably narrow.

[gallery_link num_photos=”14″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/PointWells3.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/new-build-has-rustic-style” title=”See more of the Point Wells home here”]

There are two very tall poured-concrete chimneys – Lloyd reckons the one outside resembles those remnant fireplaces you see in the countryside; the last vestige of a long-gone house. Inside, there’s a lot of timber, with all its joins and connections on show – what Lloyd describes as “an agricultural approach to detailing”. The walls are lined with rough-sawn New Zealand beech, which has a beautiful, honeyed tone. The trusses are tonka, a sustainably harvested South American hardwood. The kitchen, which sits in a timber box at one end of the main living area, is made from garapa timber. “Everything had a direction, an orientation and a grade,” says Paterson, which required thought and contemplation.

The timber windows – rosewood mullions, cedar frames – run full length down the sides of the house, opening up to the outside and framing the views. These views are carefully composed within a grid of tall, narrow rectangles that fit within the framing of the trusses. It’s at this point that you start to realise this is not a rustic shed, but a beautifully planned and detailed house.

“The way to combat the height is to introduce rhythms,” says Lloyd. “And those rhythms have hierarchies, so they march through the house and give it rationale. It’s not just a traditional window stuck in a box.” The windows – along with full-length curtains that can enclose the entire space – help to manage the rolling paddocks outside, adding to a sense of shadow and interiority.

But it’s never fussy or precious. The concrete is poured off the form, but left to weather with its imperfections on show, and the timber is left to absorb the knocks of family life. “It has piles and it has concrete that we’re not sweating over,” says Lloyd. “It’s going to do what it does – just like a shearing shed. It’s got to have that sensibility.”

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: David Straight.

[related_articles post1=”73967″ post2=”72708″]