Discover how a forgotten townhouse project in London by renowned New Zealand architect Peter Beaven still has much to offer

Celebrated New Zealand architect Peter Beaven’s London townhouses

Heading down the Archway Road in London’s Highgate, just before the Hornsey Lane Bridge, you glimpse a white jagged-edged building. To a New Zealander’s eye, its forms are vaguely familiar.

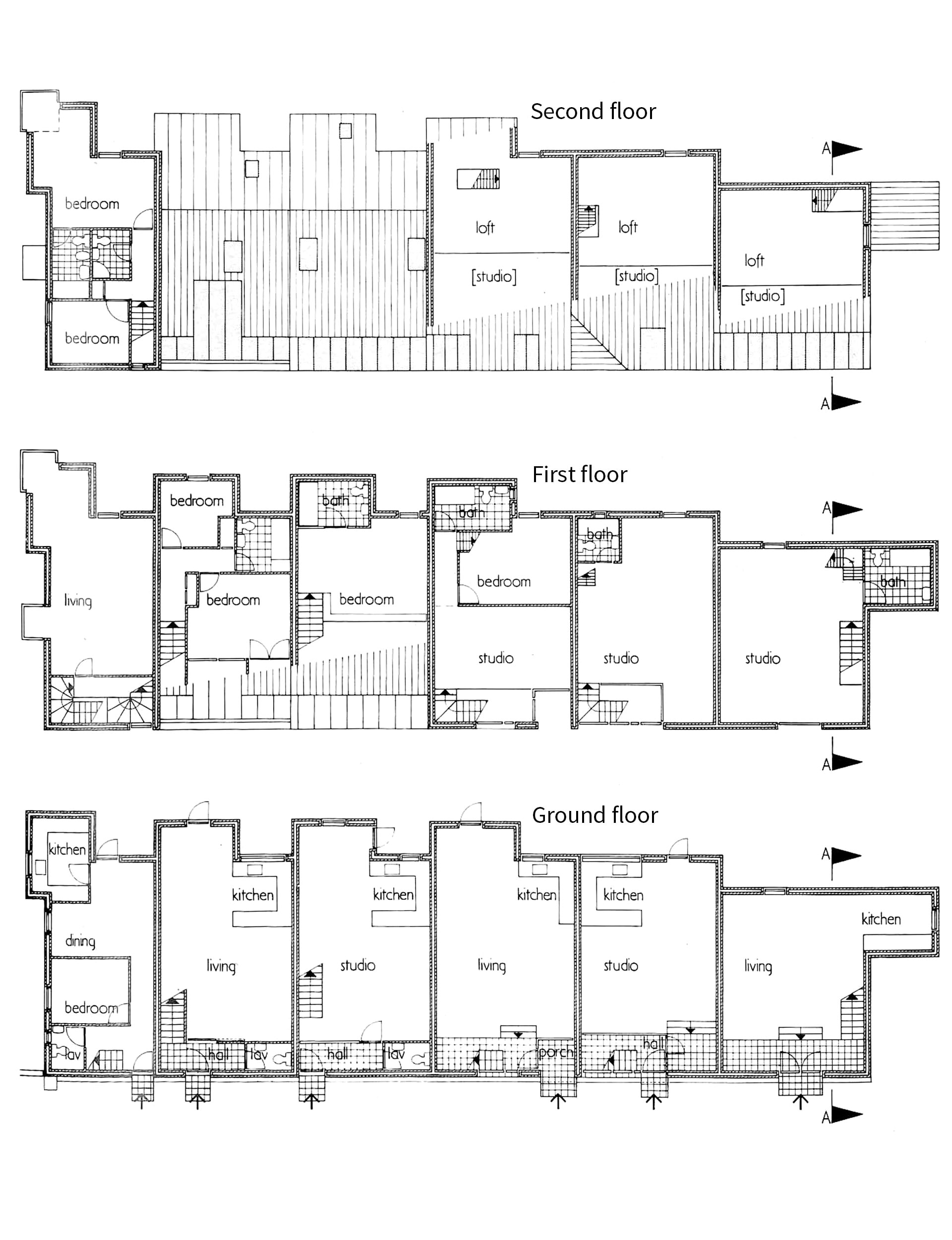

Named Tile Kiln Studios, it dates from 1982 and was designed by Peter Beaven (1925-2012). It comprises five one-bedroom studios and one three-bedroom apartment – ranging in size from 44 to 125 square metres. They are accessed from Tile Kiln Lane, a narrow pedestrian way that runs from a reservoir at the top of the hill down to Winchester Road at the bottom. It is one of only two works Beaven built during his London years; the other is a housing development in Wedderburn Road, Belsize Park from 1982.

Beaven had left for England in 1976 after closing his practice with Burwell Hunt, shortly after it had achieved national acclaim for Queen Elizabeth II Park, the centrepiece of the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch. He stayed nearly a decade, returning to New Zealand in 1985. Given the devastating effect of the 2011 earthquake on Beaven’s legacy, it’s ironic that two of his better-preserved buildings sit in anonymity on the other side of the world.

Highgate is one of North London’s most expensive suburbs and home to some of English modernism’s most canonical architecture. Tile Kiln Studios were designed as a speculative development by Ralph Forest Mackie – though the history of its first occupants is unknown. But between 2003 and 2012, it gained local standing as a hub for artists who put on an annual showcase of their work. Now, all have changed hands and some are rented out.

Beaven was assisted at the time by Marshall Cook, who was introduced to Beaven by Group Architects’ Bill Wilson. “We worked together on several projects instigated by Peter, significantly his villages on the Thames,” says Cook now. “He had no money and needed draughting horsepower and I had long, paid varsity holidays. I coopered student slave labour and we worked long hours building models and impressive portfolios from which Tile Kiln Lane arose.”

The plans are super-basic, in a good sense: square main rooms with kitchens or bathrooms as smaller cubes, simply attached. The glazed lobby roofs are characteristic of Beaven’s inventive planning (and indeed Cook’s), bringing light in while maintaining privacy. However, the small proportion of window-to-wall on the Archway elevation, combined with the trees running along the edge of the embankment, make the rear of each interior quite dark.

As was typical of Beaven, he worked to a limited budget with no loss of humaneness. Structure and materials are integrated and built with care. Window and door openings are set to half-block modules.

Timber beams and knee braces are displayed as objects of plain beauty. A stair stringer is repeated three times, becoming a balustrade of sturdy economy. Thirty-five years on, some interiors are more sympathetically furnished than others – but the construction stands up well throughout.

Tile Kiln Studios made the cover of The Architects’ Journal (May, 1982, the feature inside was called ‘Highgate down under’) and also Concrete Quarterly (July-September, 1982). Beaven’s voice came through strongly, as did his circumstances: a mid-career architect, swapping success in New Zealand for obscurity abroad and a garret-like existence. “He lives simply, even austerely, in a two-bedroom flat, overlooking Hampstead Heath… his lifestyle seems almost suicidally self-confident and is perhaps closer to that of a painter or writer than an architect.”

In both journals, the lane was treated as a detail: they gave prominence to the Archway Road side. Shot square-on to camera, the Concrete Quarterly cover emphasised the elevation’s striking play of solid and void. Inside, the magazine conveyed more the image of a hill fort, with the three-storey apartment at the bottom of the site its watch tower.

The lack of any architectural structure to the external areas was possibly budget driven. Equally, Beaven, an architect noted for this deep connection to Christchurch, New Zealand’s garden city, didn’t show much concern with planting up his buildings. Rather, they stand proud against the land. His most memorable works are cliff faces, carved from solid matter. When using concrete or stone – as opposed to lightweight timber and plaster – Beaven always made fewer but more decisive cuts, leaving it to thick walls and bold massing to animate his façades with light and shadow.

The Archway face has limited elements – pitched roofs, white blocks and black windows that are pushed or pulled, raised or lowered, stretched or rotated into a pattern with logic that’s sensed but hard to pin down. However, the individuality of each studio breaks free of any overall schema, most decisively down the lane.

Not having to deal with cars, Beaven could forgo the screening walls, driveways and garages of his New Zealand housing schemes and land the front door right on the pavement. In so doing, the lane elevation evokes something of the idyllic village footpath. Elements are freely borrowed from London’s archetypal streetscape: slate-tile roofing, patent glazing, black gutters, downpipes and brightly coloured doors, which are used frankly, without pastiche or irony.

But for all their apparent ‘Englishness’, the studios are built in a determinedly New Zealand form of construction – white-painted concrete block. The description given to both journals underscored the importance of Beaven finding a New Zealand contractor to build “in the New Zealand manner”.

There’s an irony here. Despite frequent assertions that the Christchurch School – of which Beaven was a part – drew on English traditions, block (or ‘Vibrapac’ as it was marketed in New Zealand) was an American import. American Louis Kahn made an art of block walls; the English brutalists did not. In England, concrete block is still considered an abject material, good for sub-dividing ground floor commercial units or fire-rating the back of a warehouse.

In New Zealand, by contrast, block was painted and proudly displayed as an economic substitute for stone; less a signifier of the future than the past. As Beaven wrote of Cheviot House (1966) in his posthumously published book of 2016 – Peter Beaven Architect – “concrete block was agreed as the material: 200mm-thick blocks that could have the same white-painted, textured finish inside and out. The blocks could then be modelled like blocks of real stone, shaped and manipulated to give a different sculpture for each site, and that is probably what I have always done ever since.”

So there is something in Tile Kiln Studios of an architect meditating on his experiences, a traveller perhaps not knowing whether he was going to stay or return, making an image of his current home in the material and methods of his birthplace. It’s a poignant work, made not long before Beaven stepped back into New Zealand life, a portrait, both of belonging and of not.

Words by: Giles Reid. Photography by: Mary Gaudin.

Words by: Giles Reid. Photography by: Mary Gaudin.

[related_articles post1=”71419″ post2=”71517″]