Danish modernism, Kiwi nostalgia, and a touch of grandeur converge on a one-of-a-kind site in Mangawhai, where a home of red brick and glass is dwarfed by an undulating dunescape.

This was a house that evolved slowly. Designed by Nicholas Auld of OTO Group Architecture for his Auckland-based parents, it was a project close to his heart.

Nicholas had spent years holidaying and camping in the area, and, when his parents decided they wanted eventually to retire there, it was an amalgamation of global influences and an intimate knowledge of the site and his parents’ way of life that formed the basis of an inspired design.

After spending a number of years working as an architect in Denmark, Nicholas returned to New Zealand and took on a role working for architect Richard Priest.

“It was during this time that the project began. I asked Richard if I could have the opportunity to develop a concept myself, to which he agreed, and that early design is essentially what was built.

“Part of the success of it was having a real understanding of the way my parents like to live, combined with a very personal understanding of the site and the way it changes with the weather and the seasons. There’s no substitute for just being in a place at regular intervals to really understand it.”

Approach from the street, and the new home is first encountered in a similar manner to the vast dunes, suddenly revealing itself at a bend in the road. A monolith of submerged brick seems to rise from the grasslands.

It was undoubtedly Nicholas’s time in Denmark that underscores the language of design here. He speaks of the work of Arne Jacobsen, whose visionary approach to modernism fused form and material to deliver buildings of compelling honesty and proportion; and Jørn Utzon, the Danish architect — best known for the Sydney Opera House — whose influence and work were most prolific in Denmark.

Utzon’s Kingo Houses in Helsingør are based on an additive approach, beginning with one form and moving forward from there, taking in the contours of the land and the surrounding landscape. Utzon once described the 60 Kingo Houses as “flowers on the branch of a cherry tree, each turning towards the sun”. Based on the plan of a traditional Danish farmhouse, each has a courtyard, an area for living, and an area for sleeping.

It’s these ideas that come to mind in Mangawhai, where Nicholas envisioned a home of beautiful functionality, defined by its honest materiality. As with Utzon’s additive approach, Nicholas describes this house as “a one-bedroom home that just happens to have a guest wing”. This home, too, turns its face to the sun, while a central pool courtyard creates a resort-like feel.

From the street, two brick walls curve inwards, drawing the visitor towards a large cedar-clad door sunken into the form.

“With no frame, the door appears to open or close the entire structure, [giving] a sense of fortification. As you cross the threshold of the portico, panoramic glass reveals the spectacular dunescape. In this way, the facade is a site of transformation, turning its back on the road behind and drawing you outwards to the dunes,” Nicholas explains.

The red brick continues inside, where it meets a simple palette of timber, glass, and travertine. The entry foyer is compressed, with brick on both sides and underfoot.

“This creates another threshold, between entry and the main living and entertaining space, which opens up in all directions: the glass wing.”

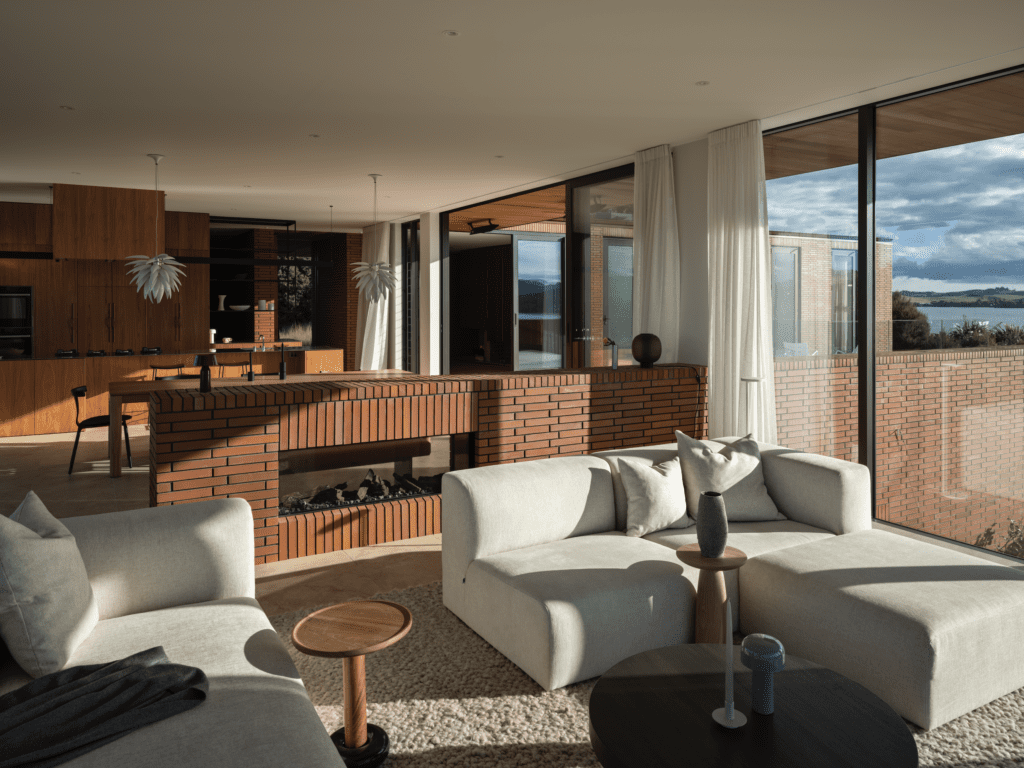

A secondary brick wall shelters three outdoor living spaces, breaking up the long sightlines to bring an immediacy to the view, and bisects indoors through the glass living pavilion to become the structure of a double-sided fireplace, blurring the distinction between interior and exterior and delineating between the otherwise open-plan kitchen and living room.

“The Danish references are subtle,” Nicholas tells us. “It’s about understanding material and proportion, and being honest to the materials while understanding how the human body wants to inhabit and occupy a space. It’s not about particular gestures or being ostentatious; rather, [it’s about] designing from the inside out and allowing the elevations to be what they are because of what’s inside. I see it as a more humble approach to architecture.”

It’s this functionalism that led to a highly successful spatial arrangement in which the L-shaped form wraps around the central outdoor courtyard and pool area.

“The house runs on a north to south, and east to west axis. The east to west axis is where you get quite opposing views. To the east, you look out across the dunes from the deck; to the west, you’re looking out over the pool from the main outdoor terrace. Here, travertine flows in and out down large steps and into the second courtyard, where it wraps away and disappears.

“By being placed right up against the house, [the pool] becomes more like a water sculpture when not in use. You also get a really interesting light effect, with rippled reflections on the ceilings. From the terrace, you look over the pool to the estuary and the two bodies of water are connected.”

The glass wing incorporates the kitchen, main living area, and dining; the former is a simple space, designed for functionality. Stainless steel benchtops are set against walnut cabinetry, while a large island invites interaction.

In opposition to this openness, the second living area is tucked into the curve of a brick wall, enclosed and intimate — separate but not secluded. In summer, it’s a cool, shady respite; in winter, with the fire roaring, it’s cosy and warm, hunkered into the depths of the house.

While there’s a rich dynamism to the spaces here, overall it’s an uncomplicated form made exceptional with a play on tension, between interior and exterior, public and private, hard and soft, and light and shadow.

“The curved, natural texture of brick softens the modernist lines of the form, and the glass pavilion provides an expansive counterpoint to the sheltered, cosy sleeping spaces.”

It functions perfectly as a spacious one-bedroom home for two, and expands effortlessly to accommodate guests.

As the sun rises, there’s an overwhelming sense of the beauty of the space and its setting. “With the sun coming through the house over the dunes, it’s lit up and gold. There’s something really special about it, and a little bit of grandeur,” Nicholas says.

For now, this place of brick and golden light remains a well-used holiday home, although its future is certain: it’ll soon become a permanent abode to be enjoyed day in, day out.