The two buildings that make up this alluring West Coast home suggest a parent/child relationship. Here, though, the child came first — with the extroverted parent, suspended above the canopy, an iteration of its introverted child nestled within the lower boughs.

There is no material street frontage to this home of two parts, tucked away in an ancient pōhutukawa grove. Ascension to the living pavilion is by way of a tiered stair that moves between external and internal environments, and takes the visitor on a journey from street level, past the minor dwelling, and up 13 metres to the highest — and main — part of the house.

At its most elevated point, this Piha home is unmistakably coastal. The cantilevered form floats within and above a vast pōhutukawa canopy, with sight-lines out to the west to the surf break and the sea. In summer, the canopy transforms into a dramatic red carpet, over which the iron sand is just visible.

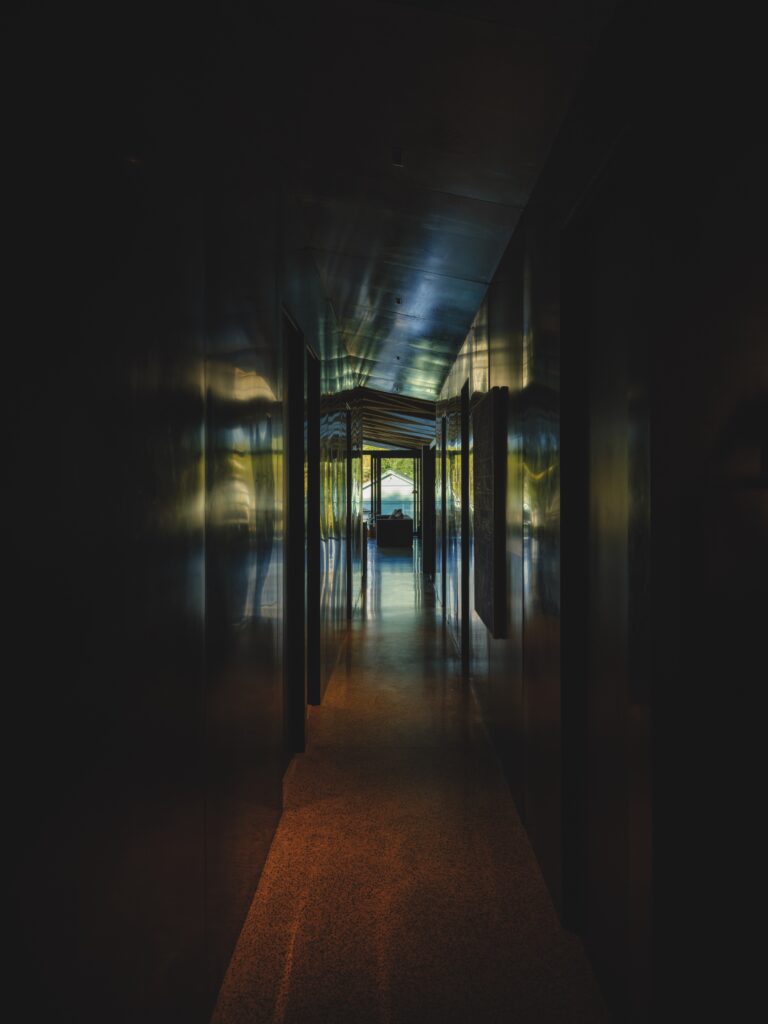

At its lowest point, it is inward facing and speculative. Surfaces are dark and brooding; a series of meditative spaces give rise to reflection, with the only view out to the native bush surroundings — a protective and natural barrier between the outside world and the internal experience.

“The site is a tertiary sand dune and had never been built on before; there’s a significant vertical rise, and at both ends of the site are these amazing pōhutukawa,” says architect Bodie Maxcey of Herbst Maxcey Metropolitan Architects (HMMA).

Bodie’s response was to thread the buildings between the trees — a move that creates a dramatic sense of them being entirely entwined within the natural environment.

“While the location is very much coastal, there are three surrounding houses, so our approach was to consider it as a suburban site, using architectural devices and existing vegetation to create privacy.

“Ocean views to the west were important, but were only achievable from the very top of the site, in between the neighbouring houses. The clients had a really clear brief, with the sleepout/second dwelling above the garage to be at the bottom of the site and the main house at the top.

“What evolved could be considered as a split personality — the parent and the child; the introvert and the extrovert. We designed the ‘child’ first; it is the original exploration of the design concept, which was refined and matured in the ‘parent’.”

The ‘child’ comprises a self-contained studio sleepout above the garage. It is an introspective space beneath the canopy, mirrored further up the hill by the much larger floating ‘parent’, which cantilevers out above the canopy and expresses itself as an extrovert — the upper level opening to the coastal views, devoid of walls, and enclosed by glass on three sides.

“While this is the clients’ main home, due to the nature of their work it would be enjoyed more throughout the cooler months, so we wanted to create a warm, moody space they would enjoy in winter particularly,” Bodie explains.

A spine of vertical steps runs from street level, past the minor dwelling and various transitional deck and garden areas, to meet the main house. Here, the entrance is compressed; it is only when you step inside that it begins to reveal itself. In fact, within this entrance you are not really inside; rather you are in an intricate rainscreen and below a glass ceiling, through which the gnarled pōhutukawa boughs wind around and above.

“It gives you the sense of entering the belly of the house, when in fact it is an extension of the external stair traversing the boundary between internal and external,” Bodie says.

Stepped down to the north, and accessible from the bottom of the stairs, are the private areas; two bedrooms, an en suite, and a central bathroom. Here, the palette embraces deep tones, with dark-stained cedar lining the walls and a salt and pepper concrete floor. The bedrooms are lined with Gaboon ply, and exposed rafters articulate the structural make-up of the building. Black-tiled bathrooms give way to operable screens that move along external Glulam beams on the northern face, creating privacy while maintaining a view onto the northern courtyard and surrounding bush.

“Coming in from the beach or down from the light-filled upper level, this private retreat is an emotive series of spaces; soothing, intimate areas beneath the canopy in which to hibernate,” the architect says.

Reach the top of the stairs — 78 in total — and the design comes into its own. “Here, people are immediately drawn to the bow of the house, which is at the westernmost point and cantilevered out into and above the pōhutukawa canopy.

“It’s the first time that you realise you are at the coast, with long views out over the treetops and to the sea. It’s that ‘aha’ moment, where the space really reveals itself.”

This is a true glass pavilion — the only wall runs along part of the northern face behind the kitchen. External sliding screens with angled fins maintain privacy in other areas; in some, the trees offer natural privacy.

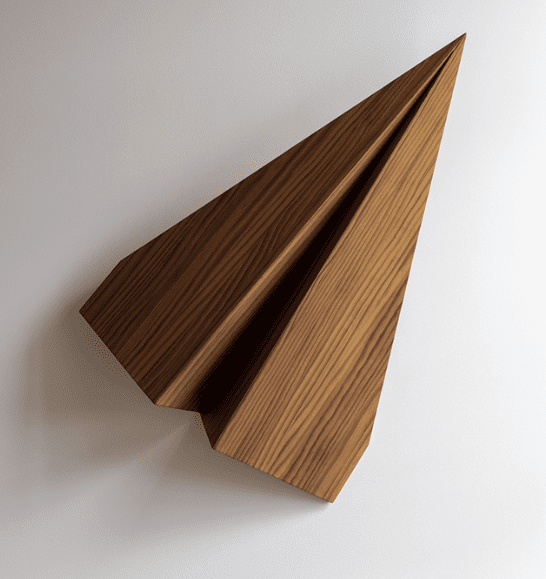

“We kept the materials really simple. In fact, only four main materials were used here: Kwila hardwood for the floors and the kitchen island, Gaboon ply for the ceilings and cabinetry, Glulam rafters and beams, and black aluminium joinery.”

It’s a sensual space, articulated with a natural rhythm. In-built seating with deep green velvet cushions combined with the dark timbers creates a palette that naturally absorbs the light and creates a soothing spatial experience.

“[With it] being a glass pavilion, we wanted to create a space where the structural elements become part of the visual language,” Bodie explains. “Where a building has no walls, the question becomes: how do you make the structure simple and sexy?”

The answer was in the exposed beams and frames that march from the front to the back, sentry-like, and which deliver a captivating insight into the building methodology.

Entirely immersed in the pōhutukawa grove that shaped its form, this is a home of subtle dichotomy that moves between compression and introspection and transparency and openness, with a playful yet perfectly measured abandon.

Architecture: HMMA

Photography: Jackie Meiring

Words: Clare Chapman