A place for relaxation without the added frills, and shelter from the elements without losing sight of the sun; Strachan Group Architects delivers a simple yet soothing statement on the shores of Langs Beach.

When out walking their dog, an Auckland couple would often stop outside a house in the suburb of Mount Eden, purely to imbibe its architecture. Although not excessive or overly attention-seeking, that family abode presents a façade of concrete and steel that exudes clarity of design and deftness when manoeuvring its densely populated context.

“We admired that house on a daily basis for a very long time,” says one of the pair (who wish to remain anonymous).

So, when they wanted to build a bach at Langs Beach in Northland — an area they have been visiting and renting holiday homes in for close to 15 years — it was an easy decision to approach the architect (and owner) of that Mount Eden house: Dave Strachan of Strachan Group Architects.

The conversations began in 2020, shortly after Strachan had been awarded the Gold Medal — the top honour bestowed by the New Zealand Institute of Architects. The owners were a little unsure whether such an accolade would mean the firm was too busy to take on relatively modest projects, and were pleasantly surprised when SGA agreed.

“We wanted to build something that would be great for us as a couple,” says one of the owners, “but also something where the boys and their mates can arrive, or, in the next phase of their lives, where they can come as couples or as a young family staying downstairs.”

The brief was simple and the site not particularly onerous; however, being a coastal property within a quickly developing street, some manoeuvring of both elements and neighbours was required.

“We always introduce the windward and leeward thing,” says Strachan, pointing out that the site has the ocean to the north-east and the late afternoon sun coming in through the other side. “So, it’s like a breezeway running right through the building.”

The brief asked for the social spaces to be on the upper floors so as to make the most out of the ocean views there. Materials there include American ash and birch plywood, which create a touch of warmth and domesticity.

The downstairs was reserved for the sons; young adults who could use the large bunk beds and their own living room, and, if needed, spread out into the yard, the outdoor shower, and have full access to the oversized garage that stores a few summer toys.

Another restriction was what Strachan calls the “artificial context” or council regulations. Not wanting to push the envelope in terms of height to boundary or any other covenant, the firm decided to stick to every rule and avoid special requests from neighbouring properties.

“We took that as a constraint,” says Strachan, “so [the house] is really just dug slightly into the ground on one side, and then folded up at the absolute maximum height we could get. Then we went pretty much to maximum roof height with an offset gable.”

Construction itself was an interesting process, with the architects taking this build as an opportunity to research up-and-coming small construction businesses in the area that showed promise and drive to take on a project that would challenge their skill set.

“I really like the idea of supporting younger people in the industry we’re in,” says Strachan, explaining that they deliberately avoided using the large, well-established companies, opting instead for Blueprint Construction, a two-person company. “We help them go outside their normal scope — give them the template for how they can make a progress claim, and support them and let them know that the door is open if they want to know anything.”

The result, as expected, is a project that becomes a calling card for all its makers and an object of pride in the possibilities of craft. This was partly possible because, architecturally, this abode seeks to remain a ‘bach’ rather than a ‘beach house’.

“It is not high architecture,” explains Strachan. “It is a relatively modest building” — and that is exactly how the family wanted it.

“We were pretty mindful we weren’t building in Ōmaha,” says an owner. “We weren’t trying to build a $4 or $5 million behemoth. This is Langs, where you’re not out of place in winter wearing a pair of gumboots — and we wanted to pitch it at that right level.”

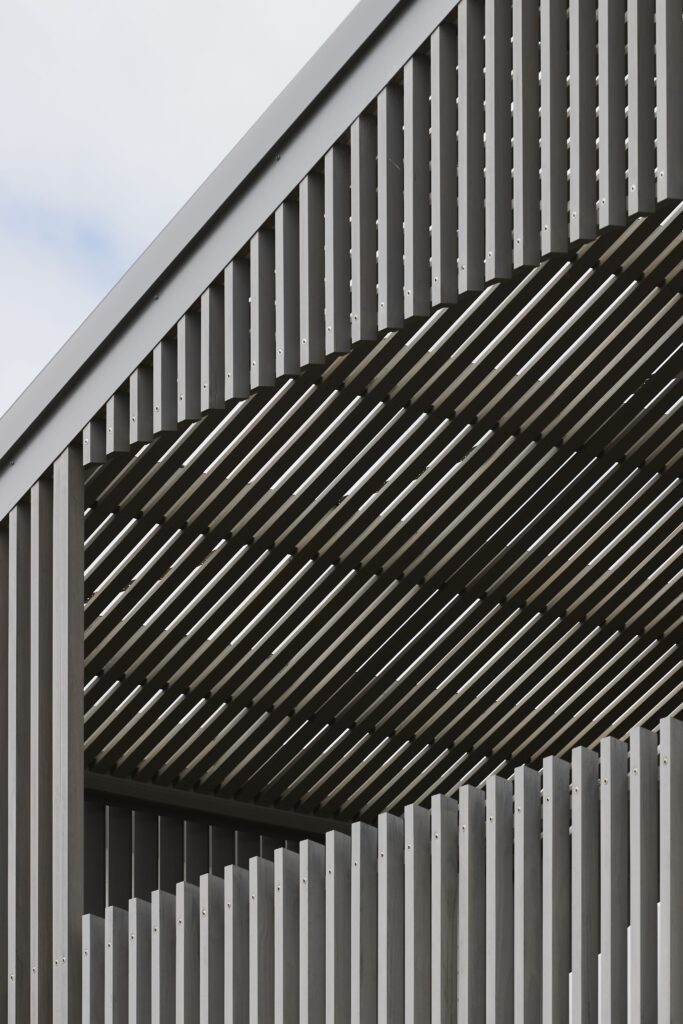

So, to create that elusive balance between personal comfort and ‘fitting in’, the architects decided to design a house with two differing frontages. Colorsteel — in a washed-out grey colour that speaks to the local sky and bleached driftwood — was used as the primary material, and made to fold up over the roof and down the non–ocean-facing side.

“This is where we get to save money that you can spend somewhere else — so it doesn’t have heaps of penetrations in it,” says Strachan of the relatively simpler side of the house.”

However, simplicity doesn’t necessarily mean the design stops working for its inhabitants. “We knew that the section has a reasonably narrow building platform that slopes away down into the bank,” says one of the owners, “but one of the other things that [my partner] and I had noticed over the years was that, when you come off the beach, the vast majority of bachs here have a deck with no sun on it.”

It was very important for them to make sure that the sheltered outdoor area at the back was not a cold space in the afternoons but could offer sunshine for post-ocean gatherings.

On the more intricate, ocean and street side of the house, there is more play of materiality and volumes. Colorsteel and the SGA signature of pine slats are visible here, adding texture, privacy, and shade. An extensive, upstairs outdoor living space protrudes from the building while emulating the gable form, giving inhabitants a chance to move around the building, following the beckoning sun.

“On a Friday after work, I can walk into the house, be in there for about 10 minutes, and just feel different,” says one of the owners. “It imposes a slightly relaxed vibe on you, which is exactly what we were hoping it would do.”