Originally built in the 1960s and left unused for decades, this farm building on the Canterbury Plains is another masterful revival by architect Ben Daly

When Ben and Dulia Daly moved back to Dulia’s home town of Christchurch, it wasn’t to the leafy suburbs and wide streets of the city. Instead, they moved back to her family farm, Arborfield, on the Canterbury Plains, a half-hour drive from the city – and into a shearing shed built by her father David Halliday in the 1960s.

Back when it was new, the shed was her father’s pride and joy, built to his design with an orange-painted steel frame on a concrete base and corrugated steel cladding. The design was typical of sheds of the day: about 80 square metres, split in two. The sheep-shearing working half had an open-slatted floor and a series of ramps, chutes and gates, while the other half, divided by a low wall, was for recreation.

By the time the Dalys took it over, the place was in poor repair. Dulia’s father – who died when she was very young – had stopped farming in the 1980s, and the shed had stood unused for decades as the farm was gradually broken up and sold or leased, leaving the farmhouse and yards in family ownership. Underneath the shed were a dozen or so sheep carcasses and decades worth of sheep shit. A tree was growing up through the floor and out one side.

But it had two things going for it. At some point – and no one can quite remember why or how – the place had been consented for conversion to accommodation. And, despite decades of inattention, the structure was sound: the steel frame was solid, sitting on a concrete ring foundation that hadn’t budged through several earthquakes. “I was out here in some real wind and it just wasn’t moving,” says Ben, of the moment he realised the shearing shed could become a home for the family, which now includes daughter Hattie.

The shearing shed is the third structure Ben and Dulia have rehabilitated – the first was a little apartment in Wellington, and the second was a little railway cottage just outside Napier. Dulia is an orthopaedic surgeon, whose career moves them around the country every two or three years as she completes her professional training. In each location, Ben completes a house project.

To call them renovations isn’t quite right: it’s more rehabilitation or re-purposing, a slow process of thinking and pondering that sees an entirely new home emerge from the shell of something utterly prosaic, working with as much of the original structure as possible. In doing so, Ben finds a new spirit, a new feeling for the place that is much more than its four original walls. His work sits at the intersection of craft and architecture, neither one thing nor the other.

With the shearing shed, Ben decided to respect its integrity and his interventions have been minimal. “I decided quite early on that I wanted to keep it exactly the same proportion on the outside,” he says. “I was worried that if you changed it you’d lose something.”

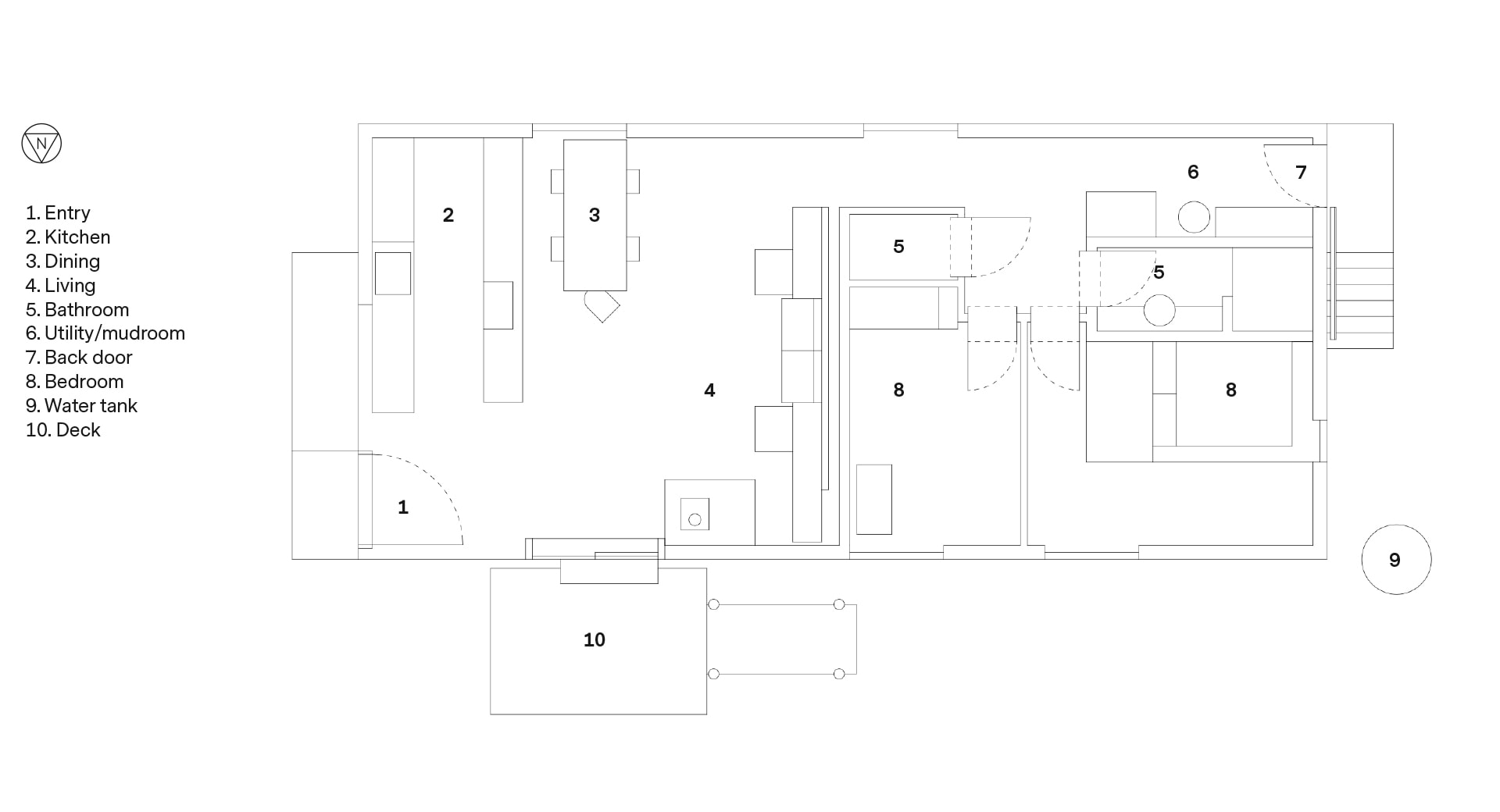

The shed sits in the yards of the old farm, beside a quiet gravel road. On arrival, you pull into the old driveway and park beside another fine old concrete barn, also built by Dulia’s dad, and where Ben and Dulia got married in 2011. You walk through a garden gate, re-purposed from the shed’s internal gates, and across a garden that will eventually house an orchard of fruit trees, then up the original concrete stairs. Inside, the layout is simple: a short hallway, off which there are two bedrooms built from Strandboard, a bathroom and toilet, and then into a high-volume open-plan living area, which is bathed in diffuse light from polycarbonate-lined walls.

Ben has preserved as much of the old shed as possible – the ceiling and orange-painted trusses are original, with insulation and a new roof above, and the line between the workers’ area and working shed are intact. He lined the old wall with slats re-purposed from the floor, and built compact secondary rooms as Strandboard ‘pods’ inside the main volume – you can still see the full height of the ceiling from one end of the home to the other. “I like the narrative of having something within a volume. The new here doesn’t touch the old,” says Ben.

The original shed had large, slatted-timber openings for light and ventilation. Now, there’s only one new opening – a large slider off the living room, which gives onto a re-purposed hay trailer that isn’t attached to the house. The windows are aluminium, sitting roughly inside the original punctures, the jambs unpainted and fixing screws on show. It’s all gloriously, deliberately unfinished. “I like the weird charm that gives,” says Ben. “If this was a shearing shed they would have got something standard and just bunged it in. So I decided to do the same – it’s always that weird tension.”

In previous projects, Ben made use of a lot of timber and laboured over the details. In Hawke’s Bay, he salvaged rimu from the internal framing to build the kitchen, and rebuilt the roof trusses and installed a black-painted vaulted ceiling behind them. It was dramatic, somewhat Japanese and obsessive, though charming. The shed is much more relaxed. He doesn’t say it, but the arrival 18 months ago of daughter Hattie no doubt forced his hand – a deadline of sorts.

As lead caregiver, Ben finished the project in fits and spurts as time has allowed, using materials that stay true to the origins of the robust shed. “Certain materials work well and enhance it,” he says, noting that the blokes at his local timber yard are thoroughly bemused by the materials going into the place. “In a way it’s those workaday materials – Strandboard is usually used as a floor, plywood is used in construction and polycarb is used in glasshouses.”

For Dulia, coming home after nearly 20 years away from the farm has been something of a joy. The shed occupied a special place for her dad, who invited the whole district to a party on its completion. A welcome place for parties, she last spent time in the shed as a teenager. “There are things that are so familiar and so like home,” she says. “It’s the little things – the smell of the farm and walking up the driveway. All my memories of Dad are in the farmyard and around this space.”

There are some new memories, too. Not so long ago, the couple captured pictures of Hattie riding a tractor in the farmyard, almost identical to some of Dulia some 30 years ago. Soon, they’ll be off to a new city for Dulia’s work, but the shed will remain their Canterbury base. “The cost of doing it up was probably less than a year’s rent,” says Dulia, “and now we have something here that is forever to come back to.”

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Sam Hartnett

This article was first published in HOME New Zealand. Follow HOME on Instagram, Facebook and sign up to the monthly email for more great architecture.

[related_articles post1=”88165″ post2=”32289″]