Nine years ago Scott Thorp moved to Christchurch to be closer to the mountains. It was here that he felt most connected to the land, and a place that ultimately inspired his photographic journey.

It’s a journey inextricably linked with Scott’s work as a graduate architect at Borrmeister Architects.

“I’ve always felt a strong connection with the land and the mountains, and I think, as an architect, what fascinates me most is not just architecture at its most basic level, which is creating shelter, but how buildings interact with the environment, and their context in the wider landscape.”

That consideration is what underpinned Scott’s Master’s thesis, which explored the symbiosis between environmental factors and the definition of architectural space, and it’s a concept he has since felt compelled to draw out and explore on a deeper, often microscopic, level with photography.

“I aim to highlight the role the landscape can play in an increasingly screen-based culture, examining the tentative and apparently dissolving boundary between the digital and physical worlds, seeking outcomes with a sense of presence, resonance, and significance.”

As a photographer, rather than focusing on a building’s place in the landscape, Scott’s work seeks to change the viewer’s perception of the landscape itself, questioning the value of the land in our lives today.

“I’m driven to give agency and a voice to the land, which is so often a passive entity within photography,” he explains.

Scott’s ongoing project, Tangibility of Light, is a series of analogue photographs that explore the unseen and the overlooked; the latent processes and qualities that make up the landscape — illuminating the way light physically occupies spaces around us, and attempting to trace the intangible systems that underpin our visual experience of the land.

“It looks at how light inhabits a space; for example, when you walk through a forest, and you have that dappled light on the path — but you don’t actually see the light until it is projected onto something.

“What this work tries to do is to isolate that light and depict it inhabiting the space, showing it in ways that we don’t really realise it exists. It asks the question: What is the character and feeling of the light?”

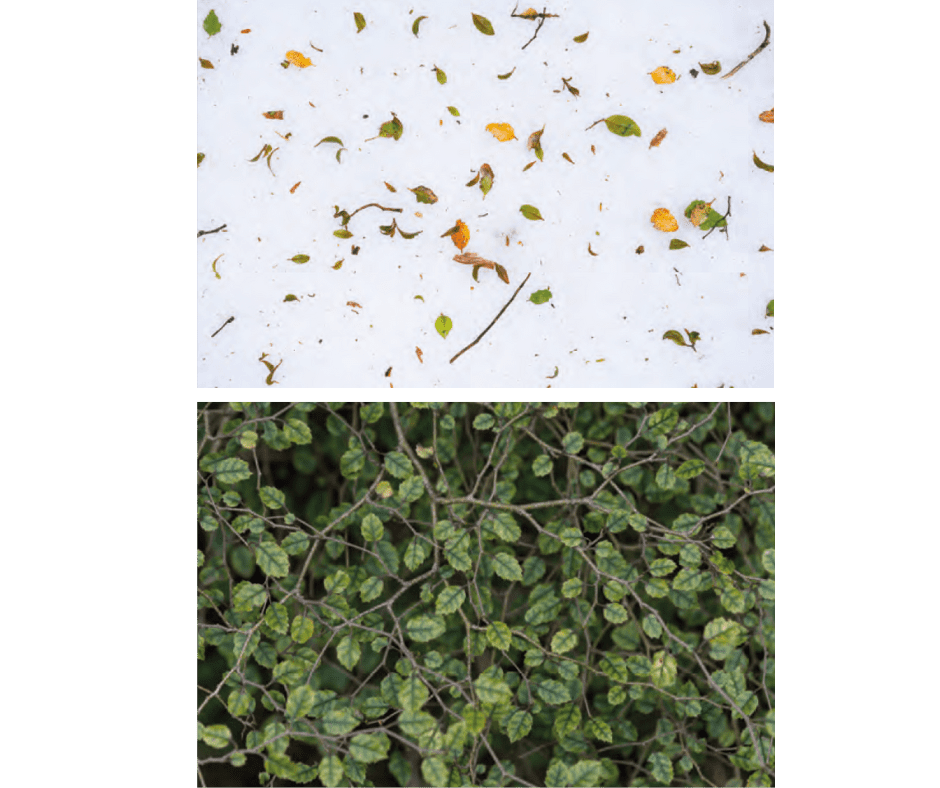

Scott’s latest body of work, Banks’ Florilegium, portrayed in upcoming exhibition of the same name, is a contemporary response to the unpublished collection of specimens, illustrations, and writings on flora from around New Zealand and the Pacific by botanist Joseph Banks.

“The photographic works in this exhibition isolate the biological systems and character of our flora. Alongside them, sculptural artefacts within the gallery represent historical changes to the relationship between people and nature.”

Each image showcases the unique adaptations and character of a single species in response to specific conditions. Shallow depth, nuanced colour palettes, intricate patterns of texture, and flattened field-like compositions are recurring themes. Being compositionally uniform yet dazzlingly complex in detail, these images offer a brief moment of meditative sanctuary; a microcosm of the experience offered by our native bush.

“A plant produces its leaves in response to light, with unique growth patterns that repeat almost indefinitely in the right conditions. In isolating these structural adaptations, the images present a system, rather than an object or picturesque scene. The lens through which these systems are presented offers a dim echo of the pressed and flattened specimens catalogued and studied in the original Banks’ Florilegium,” Scott explains.

The historical connection between man and nature is contemplated in the found artefacts that complement the photographs.

“These objects present examples of the ongoing and often tragic relationship between our flora and the actions of humanity. Fires, farming, invasive species, and the poignant beauty of the solitary remnant are represented here. Presented as individual elements, they represent single points of irreparable change in the timeline of our wilderness.”

Within this series there exists a tension between the verdant growth portrayed in the photography and the ongoing damage to nature symbolised by the found objects.

“As a country, we have a shared legacy of discovery, beauty, and destruction. This exhibition suggests that we have a duty to acknowledge and engage these elements through the complex processes of reconciliation and regeneration.”

Banks’ Florilegium is on display at Thorp Gallery, Lyttelton until 30 April 2024.