The 2024 City Home of the Year | Textured Bach by Nic Owen Architects

An abstract, monolithic, timber sculpture, this house on the hills above Sumner is a highly successful experiment of tactility and plan, of function and art.

Over a decade ago, Christchurch-born, Australian architect Nic Owen and his wife Josephine Backhouse stumbled upon a little Japanese teahouse on stilts that had been plonked onto one of the courtyards at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

This diminutive structure — set among the washed out red of the brick Renaissance architecture of the V&A — was the Beetle’s House, a temporary installation by Japanese historian turned architect Terunobu Fujimori. “It had this amazing material,” says Owen enthusiastically. “We had to research what it was, and we had to use that!”.

As is the case with many of Fujimori’s buildings, the material used was Japanese cedar that had been burnt to an inky crisp and sealed. ‘Shou sugi ban,’ as the ancient process is called in Japan, used to be a way of fireproofing buildings that housed valuable crops but, thanks in part to Fujimori, it has been catapulted into the West as a stunning technique that speaks of artisanal intent and a heck of a lot of tactility.

“We love it because of its beauty, its texture, its longevity,” says Owen, who, when he and his family moved back to New Zealand, started searching for a site on which to build their charcoal-coated nest.

The site they found was a “tricky” piece of land on the hills above Sumner with exceptional views out to sea. “It was a very restrictive site,” says Owen, who admits the challenge offered reasons to be experimental as a way to problem-solve. “It was legally created in 2007, but we were the first ones to build on it because it was a tricky triangular piece of land slipping in two directions. It had many covenant restrictions on top of the usual inherent setbacks and side envelope restrictions. I suppose a lot of people wanted to build a fairly standard single-storey house, and they just couldn’t do it on this piece of land.”

For Owen and Josephine, however, the site ticked several boxes: proximity to the surf and the chance to stretch the plan in creative ways to be able to house a family of four, a ceramics studio, and an architectural bureau without those usages infringing too much into one another’s space.

As the site is relatively raised, yet lower than the properties across the street, an early decision was for the house to “give its back to the street”, and take advantage of its north-facing sea views at the other end of the abode. It is there that the designer has put selected full-height windows, looking out to the ocean.

“What we haven’t done is just put an entire wall of windows, because we’re very mindful of making sure we don’t overheat,” Owen tells us.

“What you’ll also see on the north side is these very deep canopies,” he explains, of the metre-deep boxes that surround the windows, “like wearing a sun hat, so we don’t have to have blinds down in the middle of day, as a lot of people up here on the north looking out to the ocean do.”

Since the house is on a slope, the boxes provide a structure on which to stand and clean the windows. They also add privacy.

“It creates a depth to the building as well, because now the building feels like those windows have been quite recessed,” Owen says.

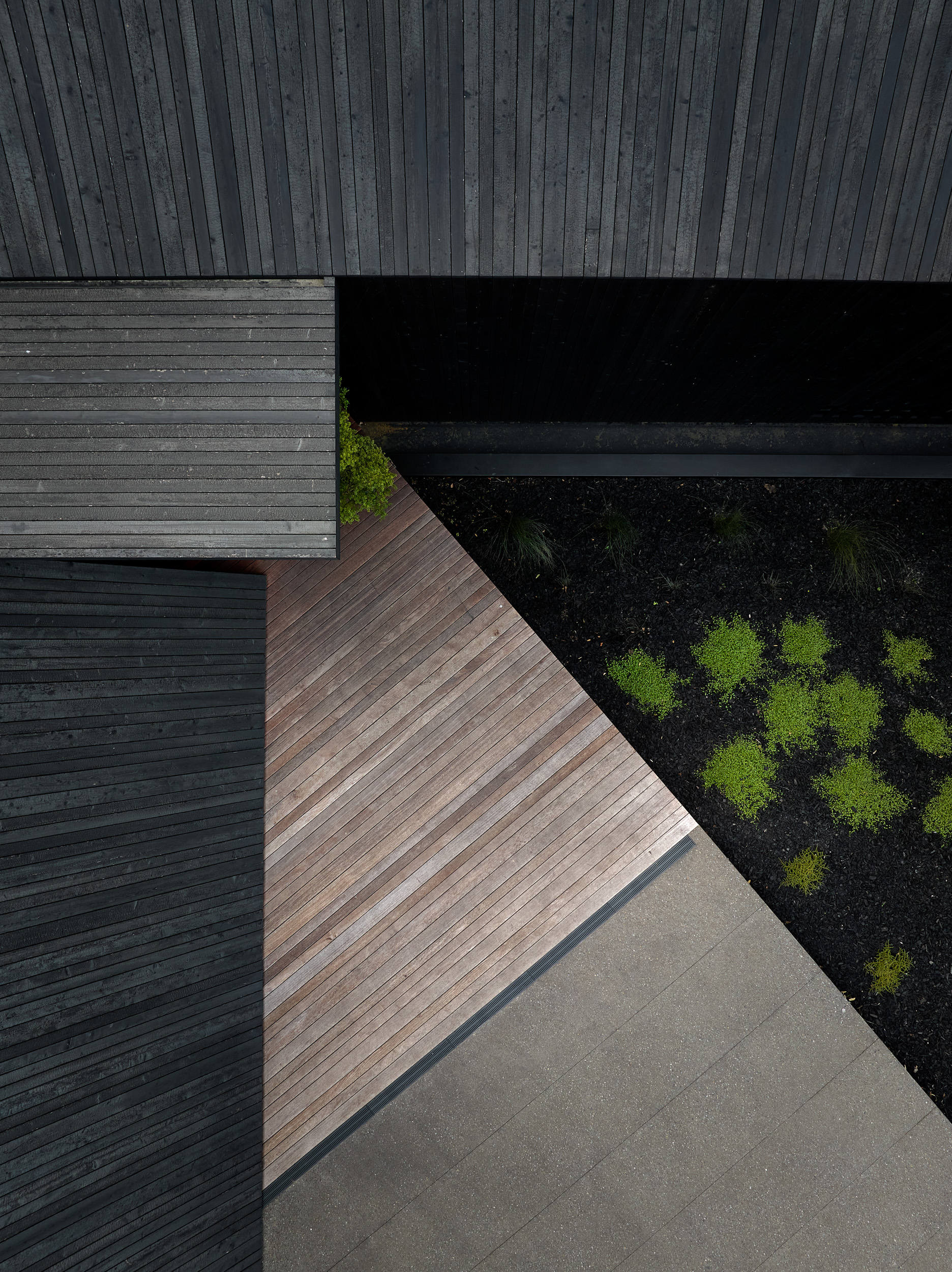

These canopies add to the house as a sculptural object, with its walls and the roof composed of one continuous material that folds and slopes.

“This is something I have done in other projects,” says Owen. “It worked well here because it created that homogenous form to ensure that the building wouldn’t be too ostentatious or visually overpower the streetscape.”

To make the form a sort of continuous monolith, however, the architect designed the façade and roof fully in the inky-black shou sugi ban — from New Zealand ash rather than the traditional cedar. The local bureaucracy required significant convincing to agree that a timber roof was acceptable.

The solution?

“A timber roof over a waterproof membrane,” says Owen. “The timber is seen as a rain screen, so, in a sense, it’s quite decorative. However, you have to make sure that the way the timber is fixed to the Butynol doesn’t end up putting a thousand holes in the membrane [allowing it to] leak. So, we have hidden box gutters underneath the timber and, since this is a high-wind zone, we have to be mindful of water that can make its way up and under flashings. We’re also in a snow area, so we have to make sure that, structurally, [the roof] can take the weight of snow.”

Arrival at this house — via a highly modulated series of experiences — quickly cements the idea that all these practical considerations have actually benefited rather than restricted the artistry of the architecture.

As you approach the house, you see a low-lying form that obstructs your views of anything past it. The closer you get, the more funnelled the experience of the house becomes, as a high-pitched raking wall provides a flourish at the entry while disguising the exterior storeroom on the level below.

“I call it the outside tunnel,” Owen tells us. Home of the Year judge, Jeremy Smith, described it as, “A sculptural move which transforms the home into a cast abstract piece in this compelling landscape.”

Then you arrive at a front door that seems stealthy, a stunning piece of charred timber that took eight trades to bring to fruition.

“You get there and say, ‘Well, hang on; where’s the door?’ Yes, there’s a bit of confusion and ambiguity. Then you open up the door and bang!” says Owen.

Suddenly, you’re greeted by the full views of the ocean spread out at a distance below you. You are facing north, and the contrast between the black timber and the blast of light is further disorienting as you are suddenly out of the tunnel and dramatically deposited in a highly urbane slice of well-thought-out interior planning.

Inside, you are confronted with a “clever, confident plan that effortlessly delivers visitors and occupants to where they would want to be,” says our other judge, Megan Edwards. “There is nothing wasted. Well-modulated connected interior spaces — modestly sized bedrooms, generous living space for children and parents, and a separate office/studio zone for the architect/artist owners on the street side, together with a discreet separate entry for clients.”

Owen says that — due to the existing housing stock of Melbourne — his office in that city is used to working on small spaces that need to perform many functions.

“I always call it a caravan design; everything is so small that every single space had to work hard and had to overlap and be multifunctional. We do have quite a few of those sorts of spaces happening in this house.”

It is in the interior that the moniker ‘textured bach’ becomes pertinent. Oriented strand board (OSB), mostly painted white, is used throughout the interior, continuing that highly tactile effect from the exterior.

The studio downstairs is perhaps the house at its most experimental. The OSB has been left unpainted. On some walls it has been omitted entirely, offering a direct view to the spray foam polystyrene insulation, which gives an almost creamy impression.

This house succeeds on many levels. It has a slick urbanity while also boasting an artisanal, handmade feel. It is experimental in materiality and form. It is clear-headed in circulation and plan. It is a delightful thing to be in.

The level of site complexity has been resolved beautifully, materials and sculpture working in tandem to give this home abstraction and charm.

As we leave, I take one last look at this form with a façade that seems almost reptilian … the architectural skin of a volcanic taniwha lying dormant on a ridge and staring out to sea.

Words: Federico Monsalve

Images: Simon Wilson, Paul Brandon

Judges’ Citation

This experimental sculptural home on the hills above Sumner in Christchurch epitomises the fusion of artistry and functionality in an urban dwelling.

A masterful balance is struck between panoramic views of the east coast and intimate retreats against the hillside. The thoughtful layout effortlessly guides occupants and visitors through interconnected spaces, each meticulously designed to maximise utility — housing a ceramics studio, an architectural bureau, and a family home — without compromising on comfort.

Drawing inspiration from the local climate, the design ingeniously integrates sheltered outdoor spaces to mitigate wind exposure while capitalising on the expansive vistas. Burnt-timber cladding and innovative blending of façade and roofing lend a distinctive character to the house, transforming the dwelling into a captivating abstract sculpture against the urban landscape.

Read more about the products and materials specified in Textured Bach

Creative Heart

The Metro Series ThermalHEART windows and doors custom-made by Vantage Windows and Doors

manufacturer Monarch Aluminium.

Into the Fire

The charred timber cladding and

hand-charred furniture and cabinetry by Christchurch-based company Chartek.