What if a house was designed to last not 50 or even 100 years, but two whole centuries? What difference would that make when it came to its design? That’s the question Tony Koia asked when creating a new home in Central Otago.

“We’re focused on the ‘whole of life’ for a house,” says Koia, founder of Koia Architects. “The building code focuses on a lifespan of 50 years, but we have to go beyond that. We should be going forwards and creating houses that can last for 200 years. If you do that, you can make totally different choices; you have different criteria for using products and measuring their costs.”

Longevity wasn’t the only priority for Koia. The house in the upmarket neighbourhood of Bendemeer also had to be integrated into the 6742 square metre site, to decide for itself how it wanted to be placed into the land, and to fit into the environs both aesthetically and functionally.

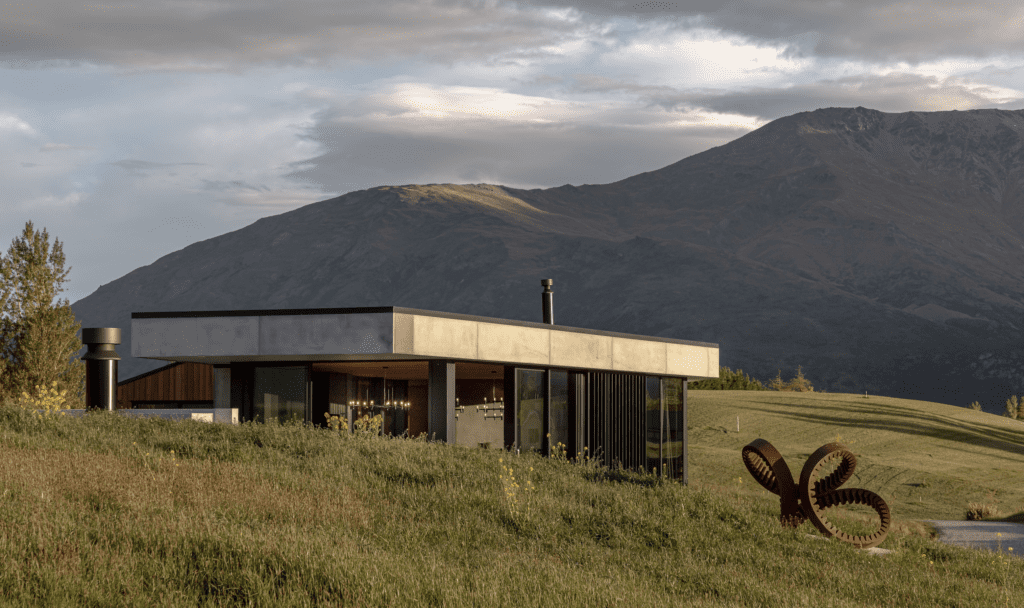

“The house, in essence, determined how large it wanted to be in the landscape,” explains Koia. “We’ve created a series of houses that are part of the landscape, where the placement, form, and materiality of the home take shape directly from the site and are a response to it. Here, the section had two small knolls, so we sited the house between them, dug it into one of those knolls, and it now sits as a pavilion on the land.”

The low profile of the 324 square metre house means it is fairly protected from the wind that sweeps through the area. A wide elevation that faces Coronet Peak and the Remarkables makes the most of the views. The concrete that was specified for the exterior utilises a cavity system of concrete panels on the top level and pre-cast concrete on the lower level. It’s not an environmentally friendly material — in fact, it creates 8 percent of global CO2 emissions — but, because the house is designed to last more than two centuries, the impact of the material is ameliorated, Koia says.

The clients insisted that the concrete have a smooth finish, in a move Koia describes as “brave. I don’t want to use the word brutal, but there is a reference to that brutalist aesthetic. There’s a solidity, an austerity that stands up to the landscape.”

A non-orthogonal shape, which was dictated by the views, the aspect, and the intention to make the structure less boxy, helps to mitigate the harshness of the concrete.

“Five or 10 years ago, our houses were all orthogonal,” admits Koia, “but there’s nothing functional about a box, except buildability. Here, non-orthogonal lines create a much less rigid feel. It’s not a box, so it feels less like a building and more like an object.”

Louvres that run the height of the main storey were added to the exterior to soften the concrete and to filter light and heat in interior spaces. A sheltered outdoor space features a large fireplace and a space to sit in the afternoons.

Inside, the irregular shapes allow the rooms to respond poetically to the functions required of them. The living room narrows into the dining area and kitchen to a point where the floor-to-ceiling glazing captures views of more than 180 degrees. Even the bathrooms are an irregular shape, with the extra space given to the three bedrooms. Large-format porcelain tiles in the bathrooms echo the concrete, while contrasting finger tiles and subway tiles provide subtle detailing.

In the kitchen, an impressive 3545mm-long island narrows as it moves towards the end of the room, mirroring the asymmetry of the room. The clients, who helped Koia with the material selections, chose a dark Dekton by Cosentino surface for the island paired with charcoal cabinetry, creating a dramatic heart to the home.

“You never know what clients will respond to when it comes to materials, but I love that process,” says Koia. “With this interior, it was an open and fluid discussion.”

Elsewhere, the interior harmonises with the breathtaking topography and the restricted exterior palette. A honed concrete slab with underfloor heating features shades of white, muted green, and brown, while cedar ceilings and panelling in the double-height entrance way that leads up to the main floor provide warmth. The impressive living room fireplace — “in case of a power cut and for the romance,” says Koia — mirrors the exterior. Both provide heating solutions that are designed to last, along with the house, for generations; the concrete construction and louvres mean there’s no need for cooling in summer.

Modernist Scandinavian chandeliers add finesse and detailing in the living area, and art collected by the couple while overseas adds personality and pops of colour.

Outside, a David McCracken Corten sculpture titled The anguish may endure forever perches proudly at the front of a knoll.

“It looks really simple, not loud,” says Koia. “It weathers and [patines], which is exactly what we want for the house in the future.”