Architect Ben Daly turns a plain 1950s railway cottage into something personal without losing its original spirit

This tiny railway cottage renovation stands the test of time

During three years living and re-working a house in Hawke’s Bay, architect Ben Daly struck up a close working and personal friendship with the artist Martin Poppelwell. The way Daly tells it, Poppelwell would say something, Daly would get offended, and then he’d go away and think about it. One afternoon, Poppelwell told Daly one thing he had going for him was time. “And I thought, does that mean I’m taking too long? Or does he mean I’m slow or lazy? And then I thought: he’s right.”

Daly and wife Dulia moved to Hawke’s Bay four years ago from Wellington, where they’d renovated a 1990s apartment that featured on the cover of HOME New Zealand’s ‘Small Homes’ issue in August/September 2015. Dulia is a doctor and when the perfect opportunity for her speciality – orthopaedics – came up in Hawke’s Bay, the couple sold the beloved apartment and moved north, eventually buying a small green railway cottage at Eskdale, just out of Napier on the main road to Taupo.

Its many and obvious flaws were overcome by the low price (less than $200,000) and its simple geometry – a rectangle with a pyramid roof – and living areas strung along the northern side. “It had a lot of partitions and walls,” says Daly. “A lot of 1950s houses are dark, but the sun comes up in the right place and it had a lot of light.”

Daly has come to call his working style ‘slow architecture’, taking a space apart and putting it back together using as many of the original materials as possible. It’s a deeply personal, idiosyncratic method that was initially a way of rethinking architecture and has since turned into something much more approaching craft. It’s not quite renovation, and it’s not really new – there’s a warmth to the result, a tactility that comes from being obviously hand made. “I really like the idea of working with an old fabric,” says Daly. “I don’t know if it’s an overindulgence, but it’s me trying to squeeze as much of myself into it to see what happens.”

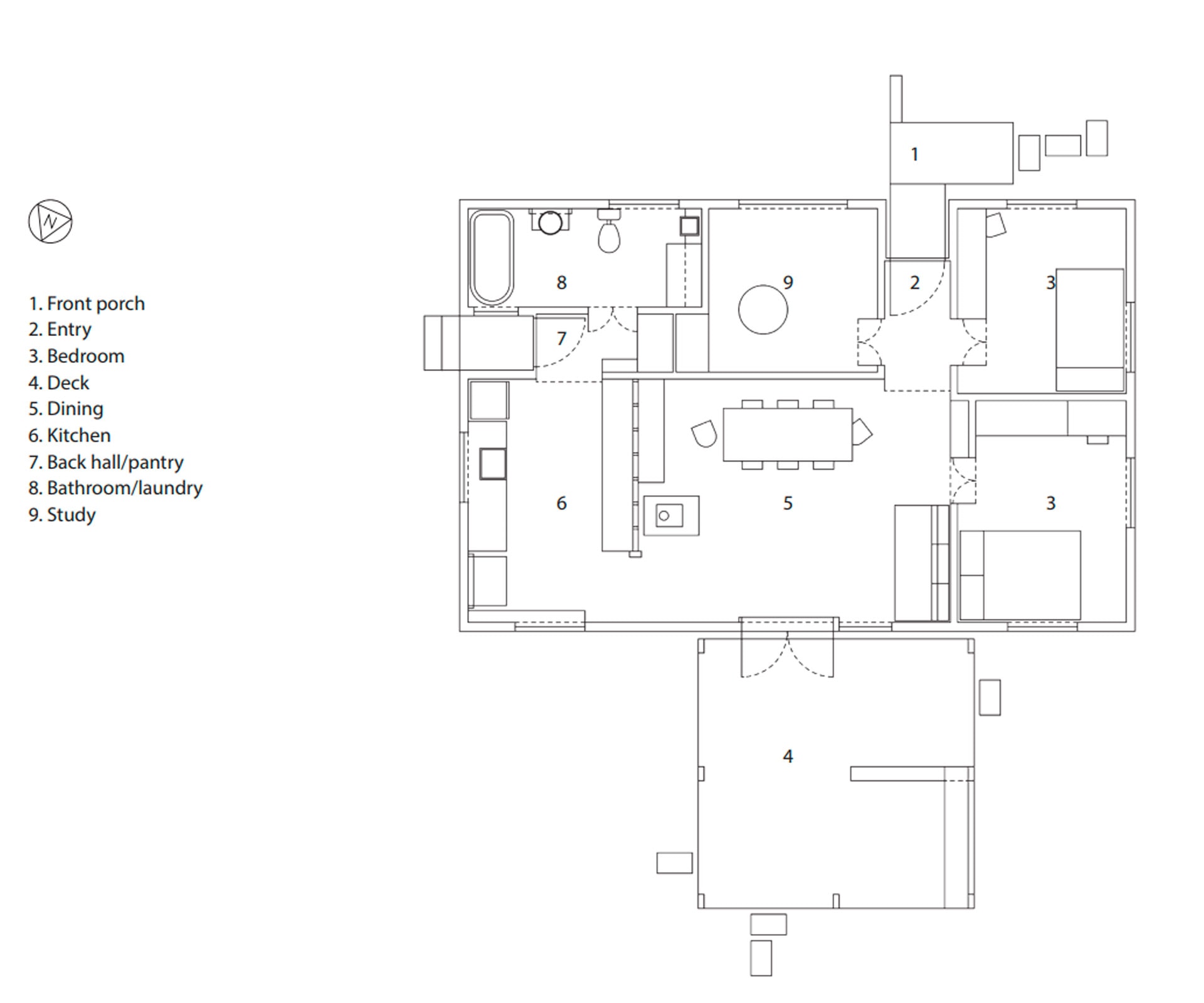

From the outset, Daly was committed to not changing the footprint of the house. At 80-odd square metres, it’s not huge, but by rationalising the spaces and introducing some volume, he knew he could make it feel generous without losing the intimate proportions of the original 1950s house. “I like it when you walk into a space and you can tell where the four corners are, and then where the ceiling is so you can make connections,” he says. “Once we made that initial commitment, it just made sense.”

Over two years, Daly pulled apart the interior and put it back together again. The house is now elemental and clever, an assemblage of shapes and boxes where once there was a rabbit warren of small rooms. His key move was to remove the low ceiling to create one volume, now lined with black-painted plywood and supported by crisp new pine rafters. Below that, he built two small plywood boxes, one housing a couple of modest bedrooms, the other housing a third bedroom or study, and a bathroom. In between, an inky black box functions as the entrance and extends outside, over the original porch.

Broadly, things are where they were. You approach the house – now painted a warm white – through a Japanese-inspired bamboo garden, and up a set of macrocarpa stairs and into the black entry box, through a rough-sawn cedar front door, into the inky interior, then out to the living area. “I did think it was important to use the basic layout of the house,” says Daly. “It’s a 50s house, and a 50s layout.”

Aside from new plywood wall linings and fixings, most of what came out of the original house went back in, or was saved for firewood. Daly painstakingly refinished the original rimu framing into a generous kitchen, with open shelves displaying a collection of ceramics and glassware. Both keen cooks, it was important to have plenty of bench space where they could work together, but it’s still compact – there’s a looseness here, a sense of just enough being enough. Knives sit in a custom-made rack on the open timber studs; there are only two drawers for utensils.

Throughout the house, Daly carefully removed the original, multi-paned windows, replacing them with larger expanses inside the opening and building new frames with timber salvaged from the house. The bathroom, meanwhile, has been reworked into an elegantly moody space, with original fittings.

Old materials lend patina, while new insertions – plywood walls, macrocarpa – give the place a rough, honest texture. Daly hasn’t sought to hide joins and fixings; he chose not to refinish the Douglas fir floor, complete with 70 years of use and the markings of removed walls. In this, he was inspired by 1970s New Zealand architecture, with its rustic junctions and sense of materials. “Fixings are really important because you understand how everything goes together,” he says. “You can see that I’ve touched all these panels because there are irregular things going on. That, to me, is the poetics of the space.”

The two-year timeframe was dictated by the couple’s next move – a new project in a former shearing shed on family land just outside Christchurch. “There’s no way I could have drawn this project on a computer,” says Daly. “It was like doing a puzzle, figuring it out on the spot with bits of timber. This is my head externalised – I couldn’t have got that if I’d had half the time.”

Words by: Simon Farrell-Green. Photography by: Sam Hartnett.

[related_articles post1=”82313″ post2=”80679″]