After a year or so of relative emptiness, Venice welcomed visitors to the 17th International Architecture Exhibition: How will we live together?

“We need a new spatial contract. In the context of widening political divides and growing economic inequalities, we call on architects to imagine spaces in which we can generously live together,” says curator of the 2021 Venice Biennale, Hashim Sarkis.

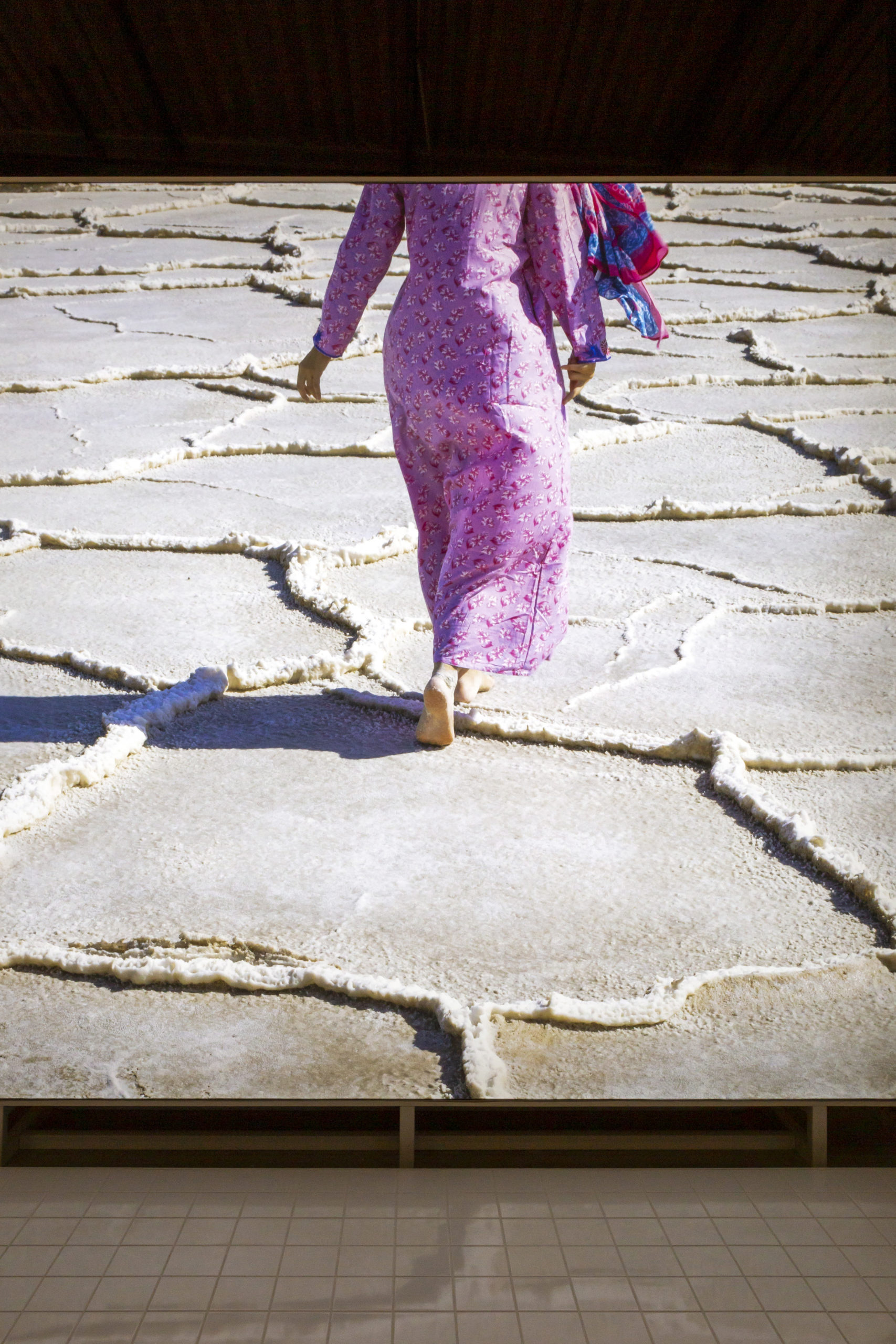

Photographer Mary Gaudin turned her lens to the opening weekend of the exhibition — an exploration of architecture in a changed world, where quiet streets prevailed and offered an enchanting, if not confronting, perspective.