A game of attractive opposites: Georgian and modernist, feminine and masculine, barn and villa — this elegant home by Ponting Fitzgerald Architects finds a sweet balance in its inherent tension.

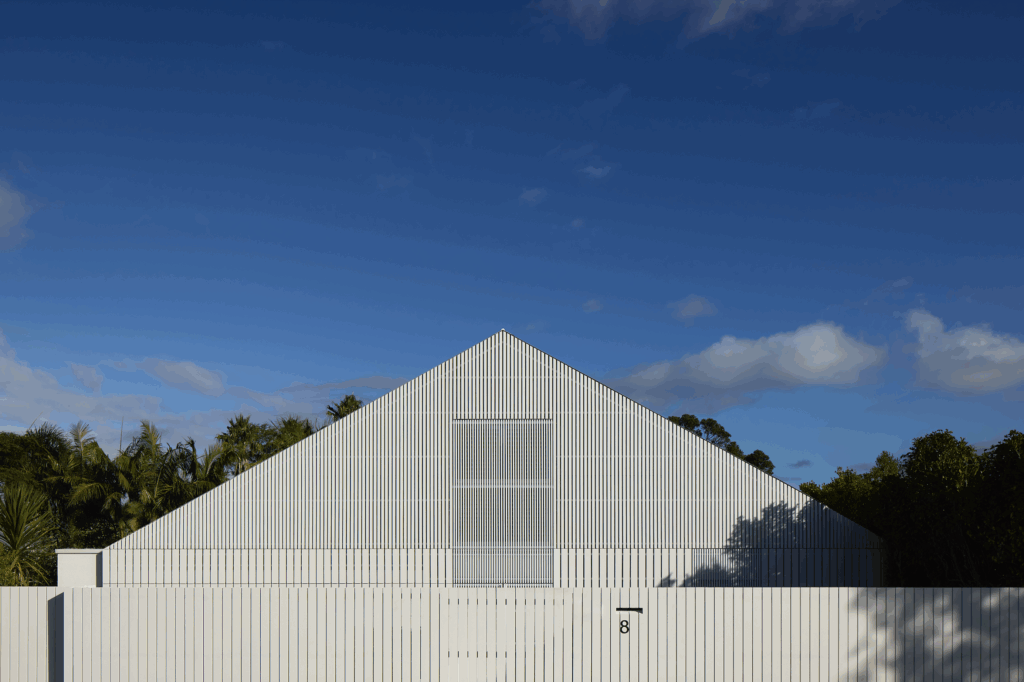

This home on a leafy Westmere street is part cloud, part ghostly figure — a sort of pixelated hybrid of a barn and a villa peeping out from behind a rather traditional white picket fence. Its frontage is composed of a quietly beautiful rain screen: vertical pine boards, going from full modules at the lower part of the structure, to half, to quarter modules as it reaches the top and dissolves into the skyline.

“It is picking up on the idea of the villa as we understand it in the New Zealand sense,” says its architect David Ponting (Ponting Fitzgerald Architects) “but getting a very fine grain character to it, making it feel more like a shed than a villa…. It’s a villa in disguise.”

At first glance, its modest, symmetrical, gabled silhouette suggests a rural shed or barn — restrained, geometric, and somewhat anonymous. Yet behind this veil lies an intricately detailed spatial narrative that draws from Georgian formality, Edwardian detail, and a distinctly New Zealand sensibility for landscape and privacy.

“It’s an elegant shed that then sort of reveals this English persona within,” says Ponting, explaining how the owners, one of whom comes from London, were deeply involved in the creative process, suffusing the design with highly personal allusions.

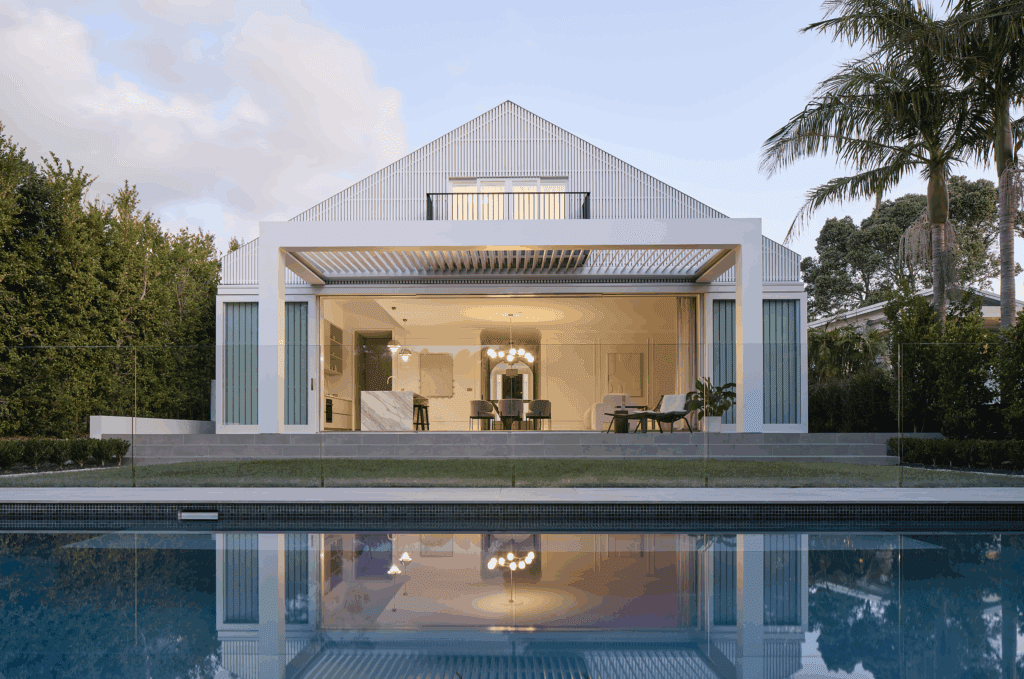

They acquired the property not for its existing dwelling (an old state house that was well overdue for an upgrade) but for the landscape it concealed: a lush, Titirangi-like backdrop of native bush. Privacy and greenery framed the brief from the outset.

“It was really about treating the house as a telescopic way of focusing on the bush,” says Ponting.

The architects responded with a rigorous axial plan, choreographing a sequence that funnels movement from the street front straight through the house to the natural spectacle beyond. This imbues the house with a villa-like formality, even as its barn-shaped shell keeps the composition humble.

The project balances this familiar exterior archetype that, upon entry, gives way to a layered procession of spaces imbued with nostalgia, craft, restraint, and, interestingly, an architectural meditation on polarities.

Ponting — whose architectural language has often leaned toward the brutalist, linear, and vertical — quickly points out how this home breaks that mould.

“Most of our projects are typically quite masculine,” says the architect, “with a feminine balance. This is definitely a house that’s more feminine but with masculine overlay.”

Whereas Ponting Fitzgerald’s most ‘viral’ projects have involved bunker-like and highly urbane use of concrete and black, sleek glazing, and sharply dressed interiors, this home is full of curvature, white, natural light, and an elegance that draws its beauty from yesteryear rather than ‘cool’.

“I’m really interested in how the balance of male to female expresses itself in a building,” says the architect, “because it’s for a couple. You tend to find that successful houses do mirror who [the owners] are but very few properties are 50/50. There is a nice energy in that asymmetry.”

The architecture finds its richness in materials and junctions, where restraint is paired with exquisite detailing. The engineered timber flooring laid in herringbone runs throughout the ground floor and stairs, setting a warm, textural foundation. The Arabescato Carrara marble in the kitchen provides a theatrical counterpoint, further dramatised by taupe lacquered cabinetry, chosen in close collaboration with the client.

As Frances Young of Ponting Fitzgerald recalls, the cabinetry design epitomised the dialogue between tradition and contemporary function; originally the fridges were integrated in the kitchen, but this created uncomfortable junctions.

“We weren’t happy with the contemporary insert of fridges, with their necessary toe kicks, next to ornate skirting boards, so eventually moved the fridges into the scullery.”

Interestingly, the scullery also comes with a working cooktop — reflecting something Ponting is seeing more and more of: this idea of having a small but practical working kitchen distinct from the showpiece front space.

The bathrooms deploy Calacatta Viola and Arabescato Corchia marbles for custom vanities, while Venetian plaster softens the walls with a subtle tactility.

Brushed brass fittings throughout — from tapware to door hardware and shower drains — add a warm gleam that contrasts with the otherwise restrained palette.

Throughout the house, the crafted detailing abounds: bespoke wall panelling establishes rhythm and depth to otherwise flat walls, while custom scotia and skirting profiles echo Edwardian precedents.

“We agonised over the wall panelling,” admits Young, acknowledging the iterative process of aligning functional storage with the visual order of Georgian symmetry.

The details, however, are restrained enough to lend the interior timelessness rather than excess or pastiche.

Circular motifs recur: a crafted arched steel door, rounded ceiling mouldings, and even the artwork selected by the clients. This repetition establishes a language of soft geometry within the house’s otherwise linear rigour.

Although referencing older styles, the house is firmly rooted within the contemporary world.

“Contemporary elegance is trying to be something that’s not contemporary,” says Ponting. “It feels like it’s pulling on [art] deco, pulling on the Georgian drivers behind that.”

Nostalgic, perhaps?

“Yes,” says Ponting, “for simpler times when it was more about craft and there were less ‘things’ around. A pre-industrial era when we didn’t make a lot, but, what you did make, you made well.”

If the exterior signals understatement, the interior delights in restrained elegance. Symmetry governs progression, with axial views culminating in the bush landscape. Lighting, carefully considered, adds drama without spectacle — skylights wash walls with daylight from above, an intervention that subtly modernises the Georgian mood.

The interiors were shaped through very deep collaboration between architects and owners. Seema, one of the clients, brought strong vision and design literacy, researching details from skirting boards to light fittings.

As Young acknowledges, “The owners had a very clear vision of what they wanted the interiors to look like, and deserve a lot of credit for what they created.”

Ponting likens the process to a painter handing their brush to a commissioner: a back-and-forth where architect and client co-authored the work stroke by stroke.

The success of the project lies in how it reconciles opposites: rural archetype and urban villa, ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ in a traditionalist sense, architectural formality and lived intimacy. It is a building that, in Ponting’s words, “you could walk past without even noticing, which is an odd thing to be proud of as an architect. But when its presence does register, you get drawn into the finer grain very quickly.”