A beach house on Waiheke Island by John Irving quietly slips from view, without having to put up a fence. Here’s how they did it

Simplicity is an art form. Making something appear effortless, when the opposite is closer to the truth, takes much more than a sleight of hand. This weekender by John Irving on Waiheke Island is recessive and quiet on its site – quite a feat given its public nature, with the beach to the north and a public walkway to the west. The design gives the owners exactly what they asked for – privacy and views – without doing anything “as crass as putting up a fence”, says Irving.

The owners approached Irving after seeing a holiday home he had designed elsewhere on the island on a similarly public site, which featured in the HOME December 2016/January 2017 issue. They liked the simplicity of its gable form and the privacy of its sheltered courtyard.

They had been happy in their original bach for a number of years, and when the need arose for change they wanted to maintain the humble nature of the old bach in its new iteration. “They definitely didn’t want to be screaming ‘here we are’ on the beach,” says Irving. “We wanted to be as low-key as possible. It doesn’t catch your eye.”

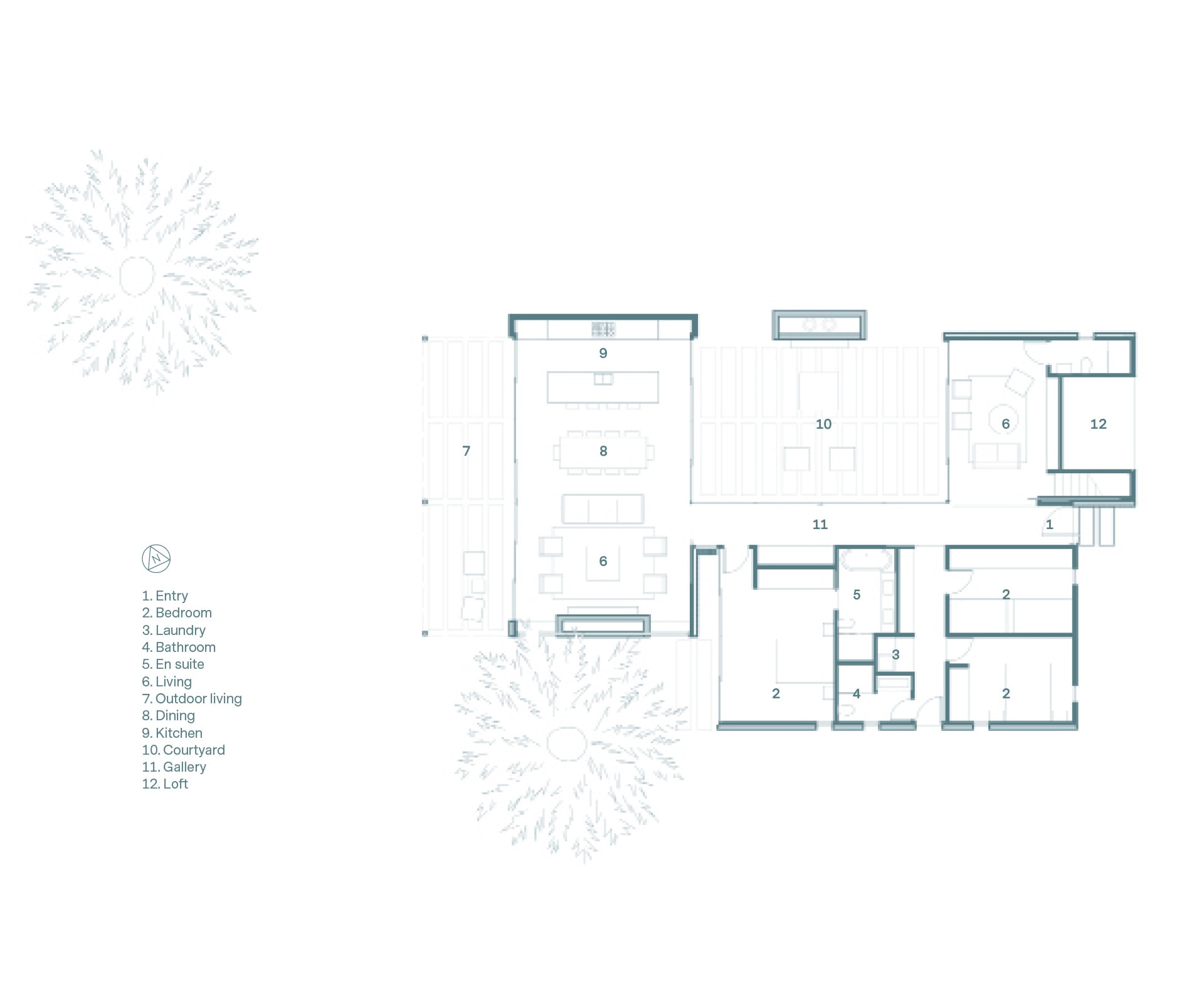

There are clever moves that ensure the 200-square-metre house recedes on the site, yet still accesses light and views. The single-storey home is a series of three gabled boxes arranged around a courtyard and set back from a slightly built-up lawn, which prevents the living area becoming a fishbowl.

Weathered, double-skinned cedar cladding wraps the house, eliminating all guttering and downpipes from view. This simplifies the appearance and elevates the traditional gable form. Irving has used the public gable ends well, filling them with high triangular windows that insert grand pictures of sky and foliage. The move enlivens the living areas with light and views.

The living areas are stacked: main living to the beach; then courtyard; then family room at the back of the house. All are accessed from the gallery hallway, which places the bedroom and bathroom area off to one side. Entry through the pivoting front door leads directly into the hallway. The solid timber door gives no clue of the view until it opens into the light-filled gallery. The sea comes into sight and the courtyard opens up on your right.

With strong prevailing winds, the courtyard was essential for shelter, and the heavily used space is completely contained within the site. From here, and the family room, sea views are accessed through receding glass walls shared with the main living area. The walls in all living areas are retractable to create flexible spaces. The kids can retreat to the living area at the back of the house, closing the doors behind them, or leave them open to the courtyard and the pizza oven that’s regularly cranked up for evening meals. Overnighting guests can close the door to the hallway, retreating from the main body of the home.

As requested, the owners have a sea view from their bedroom. “We managed to do that by tucking it into the main block,” says Irving. “It just peeks out from behind a big tree. Even though it’s quite hidden, it gets a lovely view of the ocean.”

Materiality has been given a bulletproof treatment. Everything except the stone floor is solid timber. There’s no plasterboard – walls are lined with painted bandsawn plywood. “It’s a beach house, so they didn’t want to have to tiptoe around – you want to just relax. We didn’t want timber floorboards because of the risk of UV damage, and the traipsing in and out of sand.”

The ceilings are also ply, the joins covered with battens – applied as a decorative reference to the old cribs. “It’s a little like the early fibrolite baches where the boards were put up and a batten whacked between them. Before plasterboard was a thing. The ceiling is a bit of a nod to that,” says Irving.

A similar line of thought has gone into the concealed guttering, something old baches didn’t concern themselves with, letting rain simply run off the roof. “It’s a good way to achieve seamlessness without high-risk internal gutters,” says Irving.

[quote title=”I am mildly obsessed with creating bunkrooms in beach houses;” green=”true” text=”it’s the one room that’s hanging onto its Kiwi-bach roots.” marks=”true”]

“Not that I imagine many people realise there’s no visible guttering. They sort of just perceive it as minimal,” he says. The seamless theme of the exterior is continued within. Enormous effort has gone into visual simplification, such as the hidden storage that lines the entire hallway.

And that’s the pleasure and pain of apparent simplicity – few people discern the excruciating attention to detail involved in making it happen. But the owners are thrilled. Not only did their architect listen to them, he also gave their brief care and attention, even if it meant sacrificing a little sanity in the detail. “We wouldn’t change a thing,” they say.

Words by: Jo Bates. Photography by: Simon Wilson.