Architect James Warren deftly crafts a compact cabin in a nikau glade where clever proportions and exquisite workmanship are on full display

[jwp-video n=”1″]

A tiny 36-square-metre cabin nestled in a nikau glade

Nestled in a dense nikau forest on the dramatic Punakaiki coast, Simon and Su Hoskin’s compact cabin is almost invisible: a timber box floating in the bush. Su, a biodynamics consultant and Simon, a plasterer, spent years camping out on the forest site, slowly clearing and landscaping. A key part of the brief for architect James Warren of Upoko Architects was to work within the clearings they had created.

After nearly a decade of getting to know the land, the Hoskins weren’t in a rush when it came to designing a house. “I think people are in such a hurry when they decide to draw up plans that things don’t always pan out as well as if they had spent more time at the design stage,” says Simon. “James had a lot of time to think about things and he really nailed the design because of it.”

Both architect and client speak warmly of the process of deliberate, thoughtful design, and highlight the role builder Tony Wilkins played, which required precision and attention to detail. “While it’s a small house and we had budget in mind, it also has its luxuries,” says Warren. “I think the craft is something that gives back a lot.”

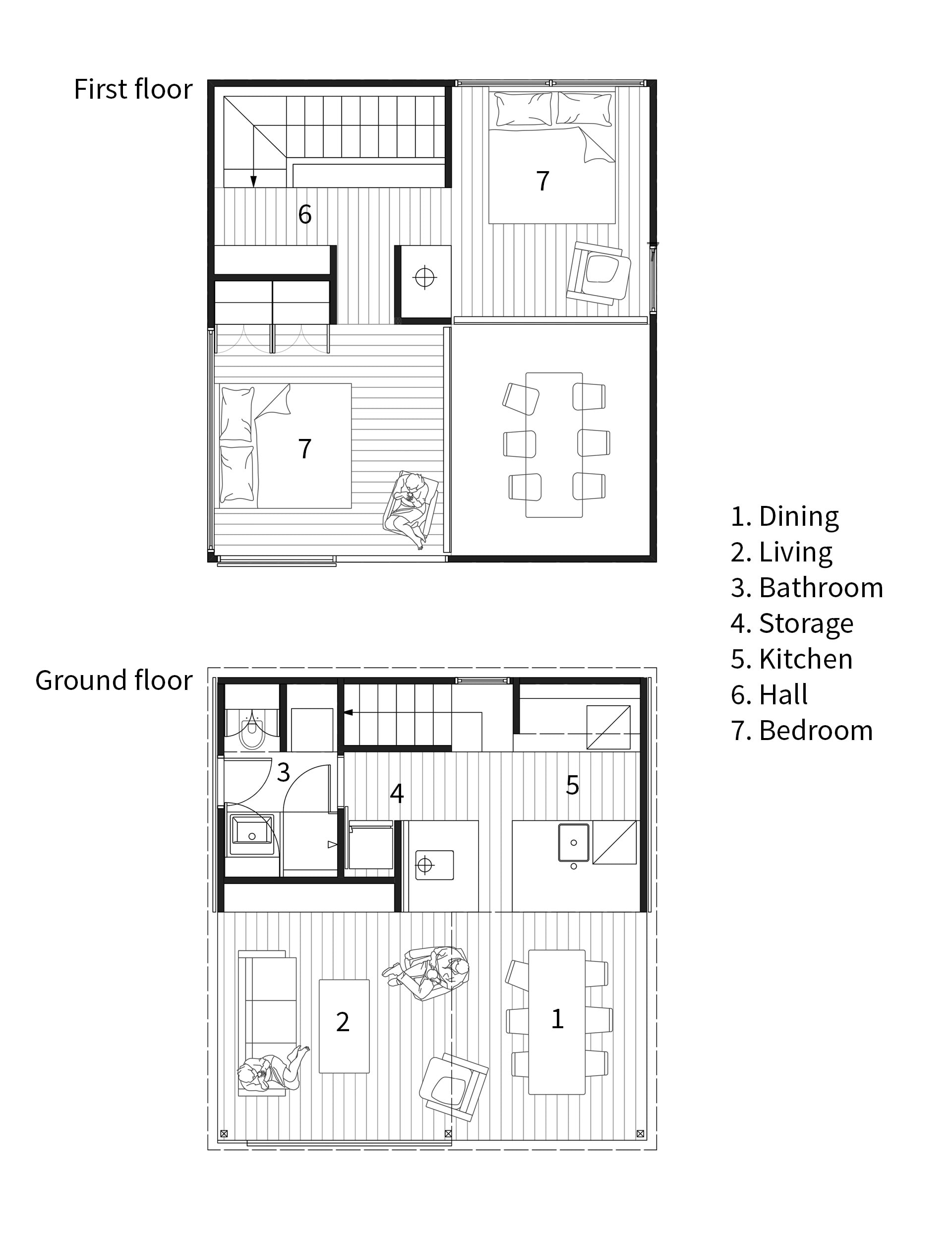

The result is a light-filled cabin with a tiny six-by-six metre footprint. Full-length sliding glass doors on the ground floor open the living room to the forest, while two open-plan bedrooms on the mezzanine create the sense of sleeping in the treetops. Glass walls give a sense of being outside in the greenery, but extensive use of timber creates a cosy cabin feel.

The secret to the cabin’s clever use of space is in the proportions afforded by the cubic design. “When you get a six-metre cube and divide it up, you get three-by- three-metre blocks to work with,” says Warren. “This happens to be a really nice shape for any room.”

A largely open-plan living room, few internal walls to formally divide rooms and a double-height space extending from the first floor all help make the cabin feel much larger than expected. Even in the tiny kitchen, deep benches allow guests to sit at the kitchen bar and enjoy the warmth of the woodburner without cramping the cook’s style. “I spend a lot of time cooking when I’m on holiday,” says Simon. “You turn around and everything’s where you need it to be.”

The cabin needed to be low maintenance, durable enough to last in a coastal environment and withstand the rough winds that blow forest vegetation around. The house has a simple gable form and a steel-clad roof without eaves, which allows the plentiful rain to wash the house down, cascading like a waterfall.

In keeping with the couple’s gentle relationship with the land, a discrete worm wastewater and sewage treatment system is tucked neatly behind the house. “We wanted to impose on the site as little as possible,” says Simon. “Everything that’s created in waste on the site gives back to the bush.”

[gallery_link num_photos=”11″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Punakaiki10.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/cabin-makes-living-small-look-easy” title=”See more of the home here”]

While the house has accommodated as many as six overnight visitors and 12 dinner guests, the cabin is first and foremost a peaceful retreat for two. At night, the only sound is the distant rumble of the sea, and visitors might just hear (or imagine) the call of the great spotted kiwi.

The sun rises gently from behind a hill in the morning, permitting a sleep-in despite the dawn chorus of native birds. “We didn’t want the house to take away from the surroundings too much,” says Simon. “It just needed to feel like it belonged there.”

Words by: Anna Jackson. Photography by: David Straight.

[related_articles post1=”71493″ post2=”71446″]