A blissfully unaltered 1958 home by Cedric Firth

Our family has lived in our home in Ngaio, Wellington, for four years. My partner, Sharon Jansen, and I are both architects, so choosing to live in another architect’s conception was an intriguing proposition. The house was designed for Ian and Gladys McKenzie in 1958 by Cedric Firth (when he was in partnership with Ernst Plischke).

We were attracted to its intelligent, beautiful and rigorous design, and to the fact that it was almost completely original. A large number of houses from this and other eras have been ruined by appalling alterations, but this was virtually untouched – it even came with the original carpet.

The owner before us had taken care of the house for 15 years. He was, in his teenage years, a friend of Ian and Gladys’ sons and said he had been determined from that time to one day own their house. When he decided to sell it, real estate agents visited for an evaluation and amidst their cries for removal of walls, ‘modernisation’ and adding here and there, he realised that another method of selling was required. We knew him and had shown him our work on the restoration of Wellington’s Sutch-Smith House (a Plischke masterpiece).

He invited us and three others to submit purchase proposals that included a price, as well as a proposal about what we intended to do if we were to become owners of the McKenzie House. We simply said we would fix its problems and raise our family here, otherwise we would leave it be – it was already perfect. This struck a chord with him and here we are, and he is still a frequent and very welcome visitor. We have stuck to this proposal because we meant it.

We have heard much about Firth’s clients, Ian and Gladys – it is a small world. They were gracious hosts who loved to entertain. They were deeply into music. They were formal and structured in all of this. The design of the house reflects that, as it does Firth’s own passions. It offers a remarkable spatial choice for socialising: the built-in sound system has speakers in the living room, study and kitchen (yes, in 1958), and the vast kitchen can be sealed off from the dining and living room.

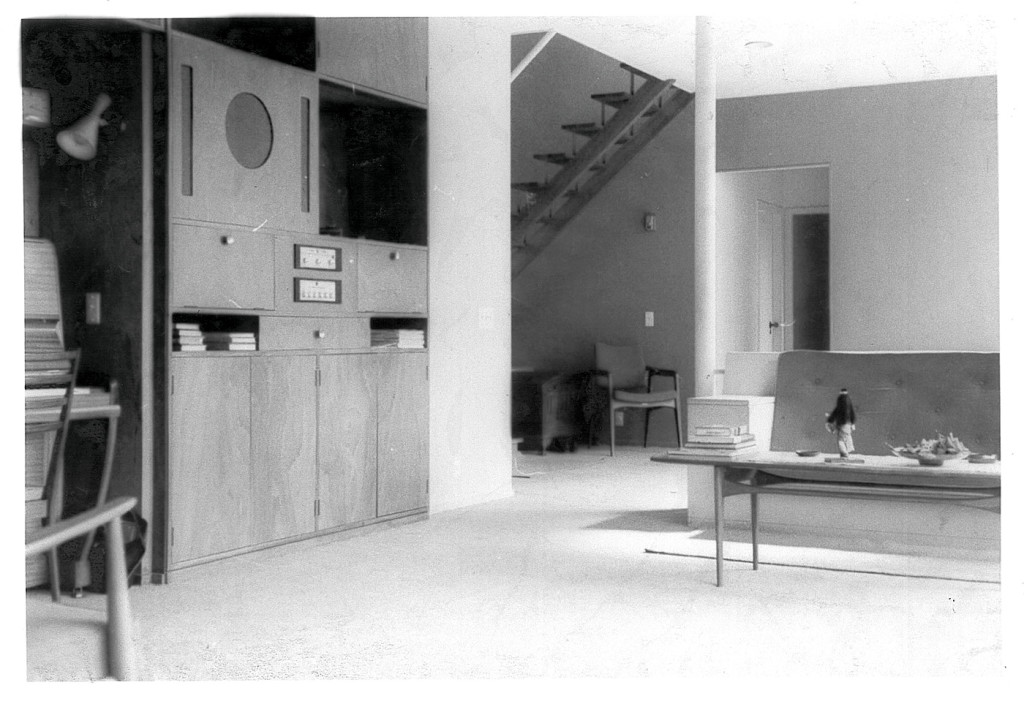

Firth brought to this his, and Plischke’s, belief in international modernism, centred on the nuclear family and the quest to create architecture that provided for all needs without surplus detail and adornment. In this house, amongst other things, this translated into an astonishing amount of built-in furniture: we have 186 cupboards and drawers (we counted them!). The house also exemplifies Firth’s belief in intelligent site relationships and transparency – not the agents’ buzz phrase, ‘indoor-outdoor flow’, but the way in which occupants can be within the landscape while still being sheltered from its vicissitudes, a useful thing in Wellington.

Concealed down a long driveway and immersed in bush, it is a classic Plischke & Firth design: box on box over three floors; a double-height, sky-lit entry atrium with an indoor garden; floor to ceiling glass; steel window joinery; ceiling-recessed lights; and, as mentioned, the staggering amount of built-in furniture. The details don’t quite get to the heights achieved by Plischke in the Sutch-Smith House (although they are not far behind), but the planning and site relationships are equal to that house, and this is where our joy in living here resides.

Aside from the entry atrium, the study (now the TV room), and the fantastic long, skinny kitchen, the clincher on our first visit was the downstairs bedroom where our daughters, Lise and Helena, now sleep. It is in a Z-shaped plan where each has her own bed, writing desk, shelves, drawers and cupboards, all built-in. In the middle is a communal space where they are able to play together. They have a strong sense of the areas around their beds being ‘my space’. The boundaries shift now and then, but effectively they are sharing one bedroom. Brilliant, Mr Firth.

Another special space for us is the study/TV room. Tiny in proportions – 2.5 metres by 2.7 metres – it features cupboards, bookshelves, a slide-out desk and an L-shaped divan seat which can sleep two people. When we shifted from our wee but neat house on Beacon Hill Road in Strathmore, we started loading all of our belongings into the storage space in the study. When we finished there was still storage left in this room alone, but we had nothing left to put away. We have redecorated this small room so that it is dramatically different from the rest of the house – dark, rich and enclosing. It is a little haven.

The living room is a further surprise. It is narrow but very long, extending visually through the dining room and the entry atrium which it sits between. It has a position and proportions that are unusual, but the room is resolved by the floor-to-ceiling glazing which allows the bush beyond to extend the space well beyond the boundaries of the external walls. The bush, in turn, ensures that it is a very private and a wonderfully serene space.

Ian and Gladys McKenzie were clearly a very fastidious couple. We have every drawing, every letter, every receipt and every single brochure for all the fittings and appliances. We also have a number of the original chairs and the original coffee table back in residence, which the former owner has loaned to us after he purchased them from the McKenzie estate when Gladys died in 2008.

The original interiors were wildly coloured – purple, lime green, salmon pink, bright red and so on – but have been muted over time. Our next project is to bring colour back into the house with deep nut-brown and vivid orange curtains in the living and dining rooms. However, the original colour scheme is one aspect that we won’t repeat.

Every home has many stories and perhaps the best one about ours is this: When our carpet layer, John Atkinson, came to measure the house he was stunned by our 50-year-old carpet. He said, “My God, this is non-crush Wilton. Look at these seams – this was laid by a craftsman!”

When John came back a few weeks later to lay our new carpet he revealed writing on the underside of the old carpet that turned out to be that of his father, who had supplied and laid it. His company, Acme Carpeting & Sewing, charged the McKenzies some £500 for that 50 years ago – we have the receipts! John snipped out his dad’s writing on the matting to send it to his sister.

Authentic modernist architecture is particularly vulnerable to contemporary concepts for living – our recent past is, unfortunately, less valued. There are many examples worldwide of houses (and other building types) like ours being unnecessarily demolished, or otherwise ruined through ill-considered alterations and additions, mostly due to a poor understanding of their pedigree.

We are very happy and very privileged to live in this house. We feel we are the current guardians rather than the owners. We, like the former owner, will only ever sell to someone who sees it that way as well. This is the way that well-made things are protected and their histories and stories preserved. –Alistair Luke

Q&A with Alistair Luke about Cedric Firth, Plischke & Firth Architects

Cedric Firth was one of New Zealand’s most accomplished mid-century architects. Here, Alistair Luke gives us a précis of Firth’s career.

HOME Who was Cedric Firth?

Alistair Luke Cedric Firth was an intellectual and socially minded architect – his primary cause was to deliver affordable architecture to all rather than an elite few. His importance in New Zealand architecture resides in his passion for the ‘International Style’, something he pursued throughout his career.

HOME What are his best-known buildings?

Alistair Luke With his practising partner Ernst Plischke (from 1948-1958), Firth worked on Massey House in Lambton Quay and St Mary’s Church in Taihape. His own projects include the memorial to Sir Peter Buck at Urenui. His master work is the Monro Building in Nelson.

HOME Which parts of your house do you like best?

Alistair Luke The serenity – we are surrounded by bush and it feels as if our house extends well beyond its physical boundaries with floor-to-ceiling glass. The built-in furniture is a joy too – very much a part of the philosophy of its style. It is extremely well-designed and we have much more storage than we can usefully use.

Photography by: Paul McCredie.