A holiday home and private escape on Waiheke Island

Passersby can be forgiven for not realising this Waiheke Island house by architect Andre Hodgskin even exists, because it is invisible from the road. Screened by thick native planting and with a circuitous approach down a rutted gravel driveway, the first thing you see is a rock retaining wall which leads you around the corner to the house: two boxes perpendicular to each other sited around a large, flat lawn.

Then what you notice is the view – out over the Hauraki Gulf to Rangitoto and Motutapu Islands and Auckland’s central city in the distance. “The owners didn’t want a monument,” says Hodgskin. “It just had to be something which was very casual, very loose and certainly very understated.”

When they contacted him in 2009, Hodgskin’s clients – a semi-retired couple with a large Victorian house in Auckland – had owned the property for almost six years without doing anything. But with four grandchildren under five, they realised it was time to build.

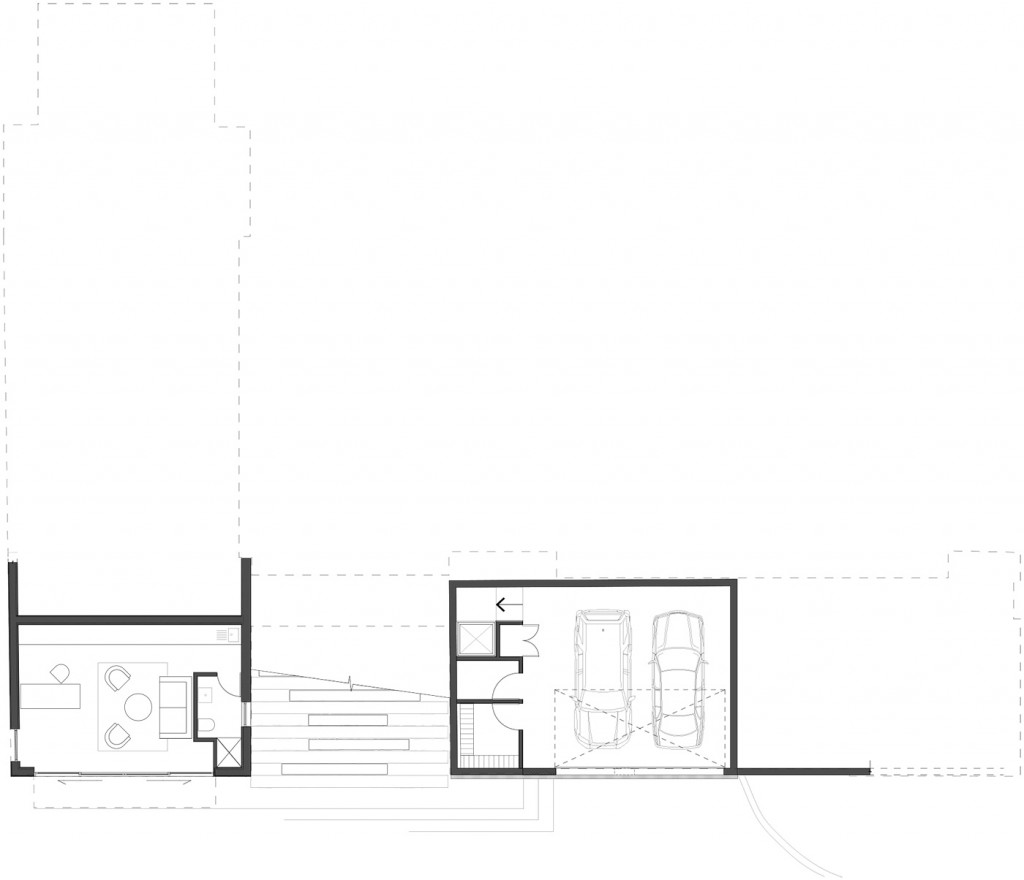

To an extent, the major architectural moves were already determined: the previous owners had camped on the site for many years – their basic, utterly charming whare is still tucked away near the house under the trees – before flattening the building platform and building large stone retaining walls and a garage.

Not that he’d have done much differently. “I can clearly remember arriving at the site the first day,” Hodgskin says of the approach to the house. “The impact of that was what I wanted to retain. The difficulty was, how do you put the house there but retain that?” His response was to create a see-through house: the main pavilion has sliding doors that disappear into the wall on either side, transforming the main living area into a sort of glorified breezeway. As you approach the place, you look straight through it at the view behind. “It’s framing it,” he says. “That was the main driver of the project.”

Despite being this close to a particularly windy stretch of the Hauraki Gulf, the home is well-sheltered. The owners reckon the wind hits a ridge in front of them and flies over the top most of the time. The house sits delicately behind a particularly beautiful stand of very large pohutukawa trees – the main bedroom’s windows look out through the boughs at the sea.

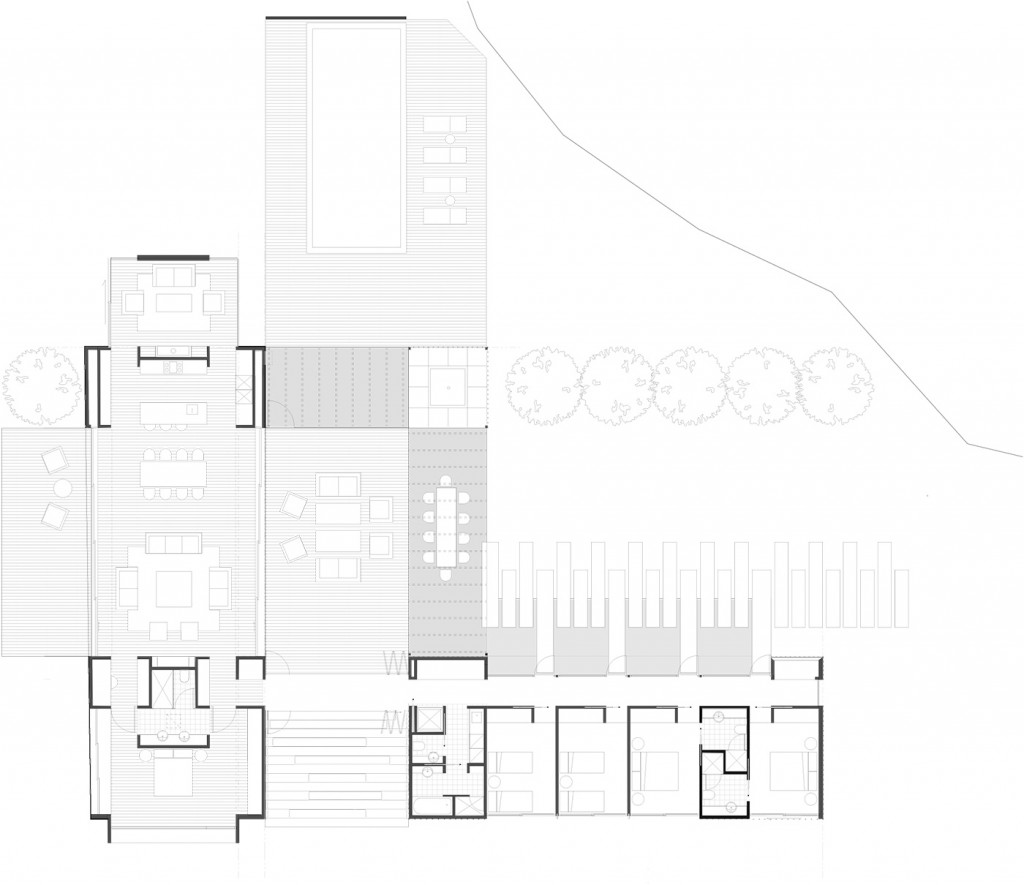

As Hodgskin notes, it is “quite a large building in terms of its brief” – six bedrooms, five bathrooms, a large garage – and fitting all that in has been a delicate process. Breaking the house in two achieves that beautifully: it allows the house to respond to what Hodgskin calls “the majesty of the site” without taking away from it. The main living box has the master bedroom at one end connected to the open-plan living area by large pivot doors, while at the other end there’s a snug.

When the owners come here on their own, they can live in just this box; when the family descends they open up the other box, consisting of “a carriageway” of four bedrooms and three bathrooms. Downstairs, dug into the hill, is the garage as well as a self-contained suite, intended for an office or extra accommodation.

The building’s discreet presence is largely due to its materials. The black-stained plywood cladding and bronzed aluminium joinery draw their colours from the ancient dark boughs of the pohutukawa, while the odd splash of green, orange and a particularly vivid yellow are drawn from the colours of the leaves through the seasons – think of a dropped pohutukawa leaf and you start to get the idea. The pergola outside is made from treated pine, rather than from something more salubrious such as cedar, and the front path is made up of unadorned concrete batons surrounded by river stones. In winter, this acts as a soak hole for the gutters.

The house can expand out to cope with a party for as many as 70 people, all the while taking knocks from ebullient grandchildren. “It was to be a playful house at the same time, or a playful canvas,” says Hodgskin, and its see-through-ness means the adults can keep an eye on the kids most of the time.

This modernity is new territory for the owners compared to the Victorian villa they usually inhabit. “We’re not minimalists,” one admits, slightly bashfully. “We’re squashy sofa people.”

And to an extent, the house does that too. It might be modern but it’s comfortable, rather than stark or hard – with clay tiles, timber floors.

“I really like using things just as they are, not having to refine them or cover them,” says Hodgskin. “Just buy something off the shelf and use it in a way that would give you an interesting or unexpected result.” –Simon Farrell-Green

Q&A with Andre Hodgskin

HOME The southwesterly side of Waiheke Island is quite exposed to strong winds. How did your design create shelter?

Andre Hodgskin, Architex Both the form and layout of the house provide a multitude of options for the occupants. The two main pavilions are linked by a walkway which can be either open or completely enclosed when inclement weather requires it. We’ve created a series of outdoor rooms and a series of slatted pergola structures for shade and further protection. So even though the house opens up in all directions, there is always somewhere to shelter from the elements.

HOME The way the land is shaped makes a handsome platform for the house. What are the benefits of shaping a site before building commences?

Andre Hodgskin The platform was formed by a previous owner for a very different design. We inherited a well-informed footprint which included the lower-level garaging and some rather beautiful stone retaining walls. The majestic old pohutukawa and other mature planting that surrounds the platform seem to embrace and shelter the building. An established context within which to place a new building can both inspire and inform the result – in this instance it softens the impact of an extensive accommodation brief.

HOME You’ve incorporated a swimming pool without it feeling like it encroaches on the site. What’s the best way to deal with pool fencing?

Andre Hodgskin Fence lines were planned as hedges which disguise the fencing and extend as fingers from the building. These break down as the landscaping becomes more natural and random further away. A short wall of glass provides security, visual amenity and surveillance of the little ones at the same time. The pool feels connected despite the obligatory fencing yet it doesn’t impose during those times of the year when it is not often used.