Pic Picot, of Pic’s Peanut Butter, had a simple brief for his holiday spot: he didn’t want a house. See how architect Julian Mitchell designed a ‘not-a-house’ for Pic and his family below

Project

‘Pic’s Not-a-house’

Architect

Julian Mitchell, Mitchell Stout Dodd

Location

Mārahau, Tasman Bay

When Pic Picot engaged architect Julian Mitchell to design something for his holiday section at Mārahau, he told him straight: he didn’t want a house. No house at all. Not an unassuming bach, or a discreet retreat. No bedrooms, even. “If we’d built a house, the first thing we were going to think was, ‘Oh, I used to like it when we had the caravans,’ you know?”

Picot, a late-blooming caravan fancier, has a fleet of three, including the vintage Nomad that began his infatuation. They’ve all been parked on the property, one street back from the beach, since he bought it five years ago because it seemed “quite a good place to put them”.

Picot had no greater strategy in mind than to share Mārahau’s still relatively undeveloped, laidback summer charms with friends and family. When the idea of instigating something more substantial on the section took hold, it was framed by the need to sustain that camping mode – to tether the caravans to an organising element rather than replace them with bricks and mortar.

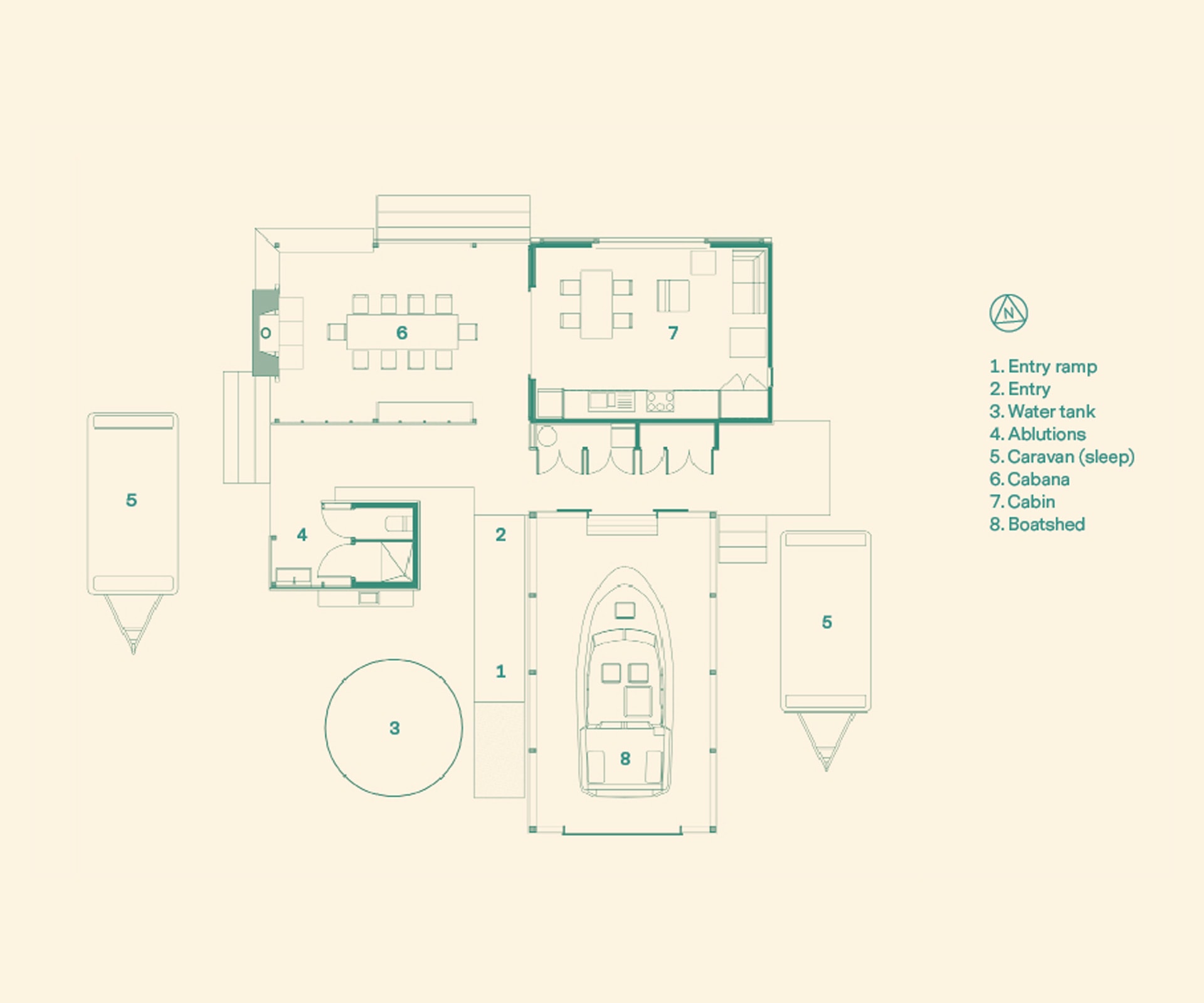

The brief was really that simple, says Mitchell, of Auckland-based Mitchell Stout Dodd Architects. “Pic said, ‘I love these caravans, I love this place, and I just want to have a bit more communal space for people to meet – and a boatshed.’ The idea was of a hub that can plug in however many caravans or campervans or people in tents arrive – like a campground.”

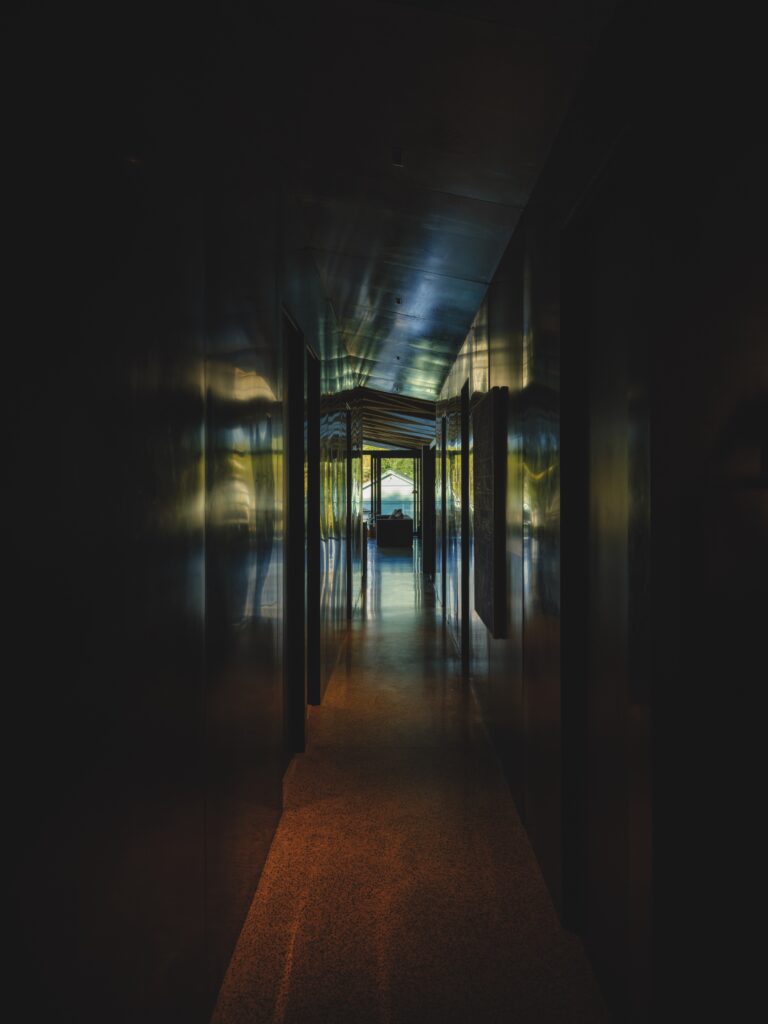

In addition to a semi-outdoor ablutions tower – stamped with one of Pic’s Peanut Butter’s famous red stars, and with a sea view from the top if you care to scale the ladder – there’s a modest enclosed kitchen and living space with a Studio log burner, which opens onto a cabana-like covered outdoor area. At its centre is a big communal macrocarpa table, and it’s anchored by a wedge-shaped brick-and-concrete outdoor fireplace that has a structural role, locking down that end of the building.

Sitting alongside is the boatshed, finished in lapped weatherboards and with side panels that can be winched open for cross ventilation. Climb upstairs and there’s a loft where intrepid kids can sleep – “a good, adventurous space”, says Picot.

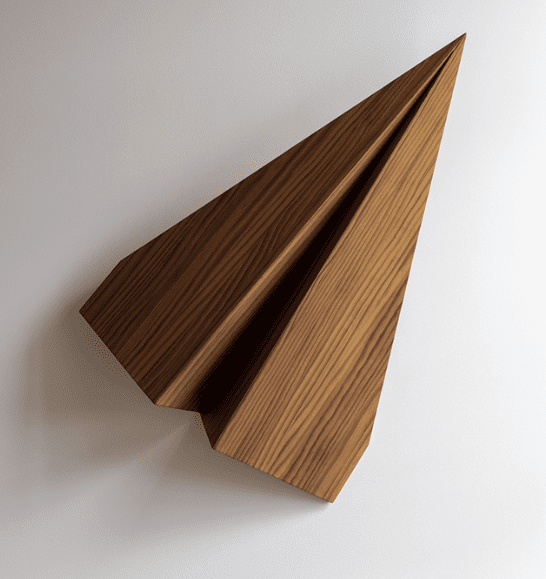

The most opulent element is the jarrah floor in the living area. Otherwise, Picot’s palace is mostly built of humble macrocarpa, a little cedar and plenty of radiata ply. “He wasn’t interested in gold-plated taps,” says Mitchell.

The architect has known his client since he was a child. His late father, the architect David Mitchell, and Picot were friends. “When I saw him 10 or so years ago, I said, ‘What are you doing these days, Pic?’, and he said, ‘I think I’m going to start making peanut butter.’ I thought, ‘Good idea.’ And sure enough, here he is. I have to say, I wasn’t at all surprised.”

The Mārahau project draws on some shared Picot-Mitchell history. “Years ago, David did a back-of-a-napkin sketch for Pic for another bach in the Coromandel, that he built,” says Mitchell. “Pic paid with a handmade leather satchel with ‘Mitchell’ written on it, which is still in the family. This time, he thought it would be nice to get the younger generation to do something for him.”

There’s another Mitchell Stout Dodd precedent for this building. The prominent ply gussets strengthening the trusses, feature in previous work, notably as beak-like forms in the ‘Otoparae’ house near Te Kuiti. That project, which won Home of the Year 2005, was a collaboration between Mitchell and David and Julie Stout, and was modelled on a tramping hut. But the bedroom-less Mārahau structure is another degree of humble.

“It’s the most simple in terms of mechanics, and that’s the refreshing thing about it – its simplicity is its beauty,” says Mitchell. “It’s a model that can be used more often, I reckon – the notion of a holiday hub rather than a holiday home. There are a lot of people out there who are quite happy with a caravan or a little shed, and really all you need is the civilising influence of a decent table that everyone can be around, some running water and a decent roof over an outside room.”

It works for Picot, who grumbles about the emerging signs of gentrification at Mārahau – lamp posts and concrete footpaths have made an appearance. “When you sleep in the caravan and get up in the night to go to the toilet and it’s raining, you get just that little bit wet, just enough to remind you that you’re outside. People who stay here really like that: ‘I feel I’m on holiday.’”

Recently, Picot splurged on a Sealegs amphibious craft for the boatshed – his first fizz boat after a lifetime of yachts – to remove the hassle of launching at Mārahau’s heavily tidal beach. He’ll spend most of his summer ‘camping out’ here, joined by children and grandchildren and whoever else bowls in. No bedrooms? No problem. “We’ve got spare jackpoints,” he says.

Words by: Matt Philp. Photography by: Lucas Doolan.

[related_articles post1=”1626″ post2=”94818″]