A private tramping hut in the Orongorongo Valley embodies the prelapsarian spirit of the people who built it by hand 56 years ago

Keen trampers built this hut in Orongorongo Valley with their bare hands

There can be few buildings in New Zealand that embody friendship quite so profoundly and quite so uniquely as tiny ‘Taihoa’. The private tramping hut, built by school mates more than half a lifetime ago, has been both source and sustenance for the friendships forged in its making – relationships that, in the years since, have grown and matured like the bush that surrounds it. And the story of Taihoa’s making – in an almost prelapsarian New Zealand of good keen young men and women – and the history of its continued existence in the wilds of the Orongorongo Valley near Wellington, are yarns best heard on the walk to its door.

On a fine, cool morning in early November, with wild winds promised later in the day, I joined six of its owners and guardians – including Wellington architects Philip Porritt and Chris Cochran – on the gentle, 90-minute ramble from the Rimutaka Forest Park’s Catchpool carpark to Taihoa, which sits hugged by bush above the Orongorongo River. The hut, Porritt said, as we walked through stands of red beech, rimu and nikau, might not have been built at all, if not for

a remarkable woman, Gwenda Martin.

The year was 1962, and Martin, a biology teacher and leader of the tramping club at the not-long-established Wellington high school, Onslow College, guided a small party of its students to a hut set deep in the Orongorongo Valley, which lies in the southern Rimutakas. Called ‘Paua’, the hut was one of scores already dotted down the valley. Orongorongo Valley is to Wellingtonians as the Waitakere Ranges are to Aucklanders. But it is a peculiarity of the valley that, for nearly 60 years until 1980, the Wellington Water Board, which administered the area, allowed private hut-building.

Shaun Barnett and Chris Macleans’ comprehensive Tramping: A New Zealand History, calls the area the country’s largest enclave of private huts on public land, with dozens of rough shelters and cosy huts being built from the 1920s. By the 1960s and 70s the number was well above 100. At first, Martin told Porritt and fellow student Maralyn Clark that she had a mind to buy an existing hut. At Clark’s suggestion, she decided to build one instead.

“During the school tramping trip to Paua hut,” says Porritt, “Gwenda and Maralyn quietly came to me in the afternoon and said ‘We’re off to look for a hut site, do you want come and help?’ Gwenda said she wanted it to be by a significant tree. So we found this great rātā and decided that would be a good site.

“In those days, the land belonged to the Wellington Water Board, and we chose a hut site, drew it on a map and said to them ‘We want a licence to build a hut’, and it was just automatic. They gave us the licence and it was one pound a year. Once we had the permission, we started planning.”

In the first of Taihoa’s many beautifully bound log books (there was a self-conscious recording of its history almost from the moment it was conceived) there is, among the black-and-white photographs of Porritt and his friends as bright young things, a drawing made by him of how the hut might look.

Over the summer of 1962-63, Martin and about a dozen students – including Porritt, Cochran, Jill and Ian Goodwin and Taihoa’s chief documentarian Allan Sheppard – built using second-hand materials, native timber sourced on site (“You’d go to jail if you did that now!” Porritt laughs) and a lot of native, as well as naive, know-how. “People did what they were good at and, in some cases, what they weren’t good at,” says Ian Goodwin.

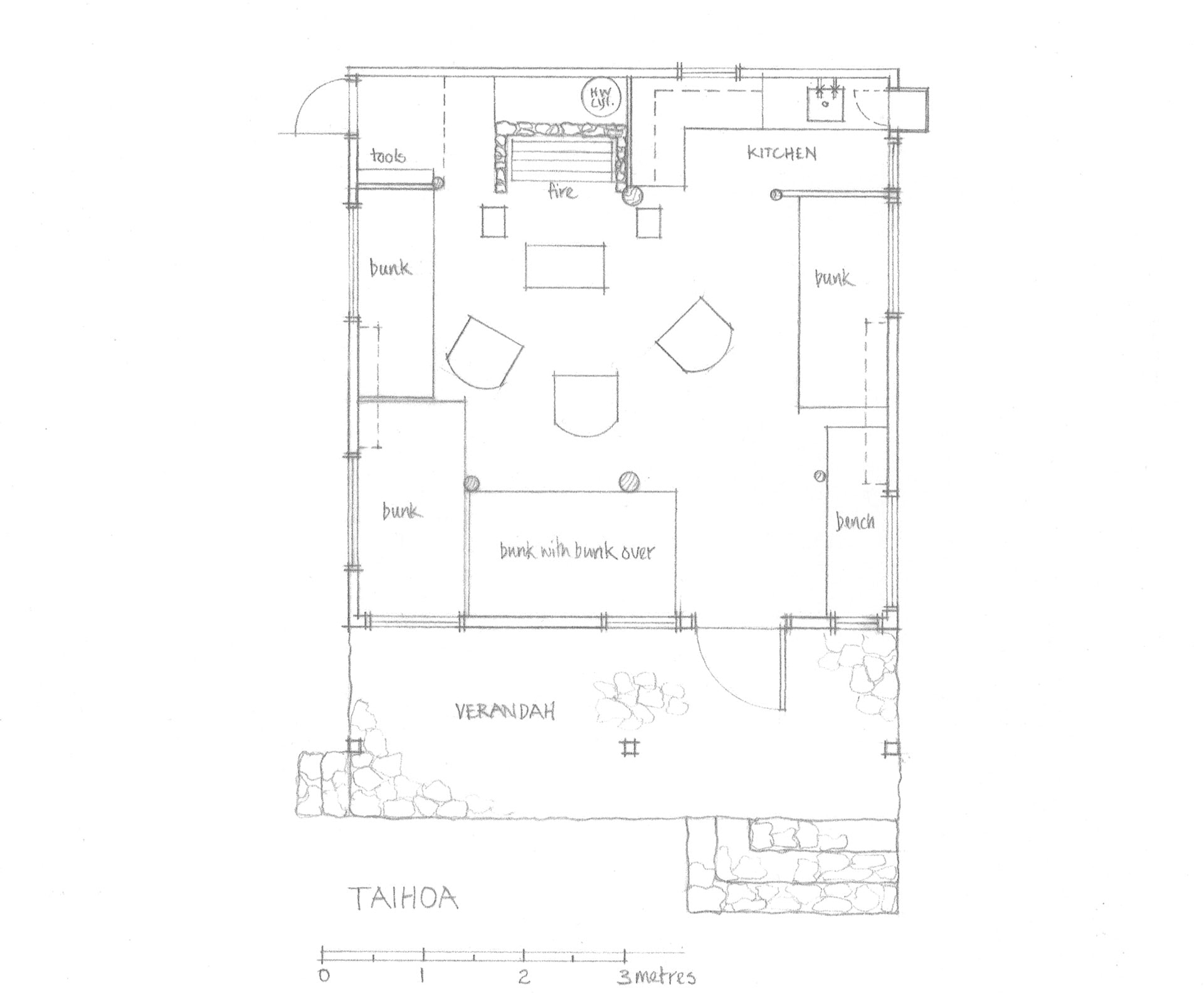

“Gwenda and I talked about how it should be and she had some pretty clear ideas about what the space required because she tramped a lot,” says Porritt. “We agreed on a design and started collecting second-hand windows, and that sort of influenced the plan. There are a whole lot of horizontal windows, which I got from a neighbour, that set the tone.” Martin also wanted black rafters and a white ceiling and walls: she showed the students pictures of churches, even though she was the last person you’d think of as churchy, and she wanted a slight Māori influence – you can see both those influences in the hut.

“There was a rumour going around the valley,” says Porritt, “that there was a teacher and a bunch of kids building a hut in the Orongorongos and it ‘won’t last six months’. But we were completely confident that what we were building was going to last forever.”

[gallery_link num_photos=”10″ media=”https://www.homemagazine.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Orongorongo6.jpg” link=”/real-homes/home-tours/nz-tramping-hut-design-orongorongo-valley” title=”See more of the tramping hut here”]

The name Taihoa – it translates variously from Māori as ‘by and by’, ‘wait’ and ‘no hurry’ – was chosen by Martin. But a better name for the hut now might be Whare Tongarewa, or museum. Once at Taihoa’s door, you find a treasure trove of the group’s shared history – a mural of the hut’s building, the log books, carvings, tools and knickknacks – along with a fine library, including some rare first-edition New Zealand books, such as Colin Kane Bell’s beautifully illustrated Po-Ling: The Cook from Ti Tree Point. The mural in the hut was painted in the first year by one of the hut builders, Rikki Duncan, and represents the digging of the hole for the outhouse – designed as a tribute to Wellington’s Byrd Memorial.

If a museum is what it now seems, it is a living one. The hut continues to be used, cherished and assiduously maintained by the original builders, their families and their friends. Martin, who died in January, visited Taihoa for the last time in 2007 for the hut’s 50th birthday.

She was 86. More than 70 people came from all around the country to celebrate. And there was, as there had been for so many significant birthdays for the hut and friendships it fostered, a home-baked cake decorated in a homage to the hut’s quaint, rustic lines.

“Gwenda said that last time, it wasn’t really the walking that was more difficult so much as hut life and sleeping on a hard bed and people being around,” says Jill Goodwin. “Which is sort of sad, because that’s what tramping is! But she enjoyed it. She broke the mould – she was amazing.”

And so, too, is her legacy, Taihoa.

Words by: Greg Dixon. Photography by: Paul McCredie.

[related_articles post1=”74511″ post2=”74134″]