An architect and interior designer’s surprising shipping container getaway

When it comes to designing their own homes, my parents are far from traditional. My father Greg Noble is a New Zealander who trained as an architect in Scotland and my mother Georgie Noble is an interior designer.

I grew up in the UK and when we left London for Shropshire, it was to a derelict stone house with no windows and no doors. We slept on straw mattresses and lifted at least a metre of cow poo from the floors. After the building was restored we named it Pooh Hall.

When we came to New Zealand it was to storage sheds on Great Barrier Island, where we lived through three months of mud while we built an off-grid home made of steel and tensioned membrane.

My parents sold that Great Barrier house some years ago. This year, they set a customised storage container on land only accessible by sea, just north of the Bay of Islands. The land is isolated and incredibly well-sheltered in a small bay and estuary.

In July last year Greg found the property advertised for sale in a tiny blurb in a local paper. That weekend, Georgie left me a message saying they had gone up north on a “wild goose chase”. Six months later my parents would enjoy one of their longest-ever holidays there, with friends coming and going by boat.

The container on the site was bought in Christchurch. It is just over six metres long and opens out completely on one side. My parents then customised it, lining it with raw macrocarpa boards, shelves and a washing-up bench. The doors, when opened, fold around at each end, forming an enclosure where they are attached to a deck with a brass showerhead, which shares the same plumbing as the sink.

Most people would shy away from locating a two-and-a-half tonne container 30 metres uphill from the high-tide mark in a place where no vehicles – let alone cranes – can travel. But Greg saw it as a challenge. The fit-out had to be prefabricated and everything packed into it, as it couldn’t be transported with the deck down or the roof on. My parents planned ahead, so that all the fittings were prepared for transportation and assembly at the site.

Then we waited. The bargemen needed a three-day uninterrupted run of fine weather and to land in daylight, at high tide. When the day finally came, the container was dropped onto log rollers and manoeuvred, pushed and pulled by six men using only hand winches and jacks.

The container doubles in size by virtue of the deck which, when folded down, opens flush off the front. The roof was constructed (after the container came on site) with a large overhang so it doesn’t overheat and the deck never gets wet when it rains.

Then came the water tanks. We rolled an empty one up to the container. Then we pumped water from a full one up to the empty one, then rolled the second one up. We unpacked the furniture and supplies that had been stored in the container before it was moved on site and by the end of the day we had made ourselves a home.

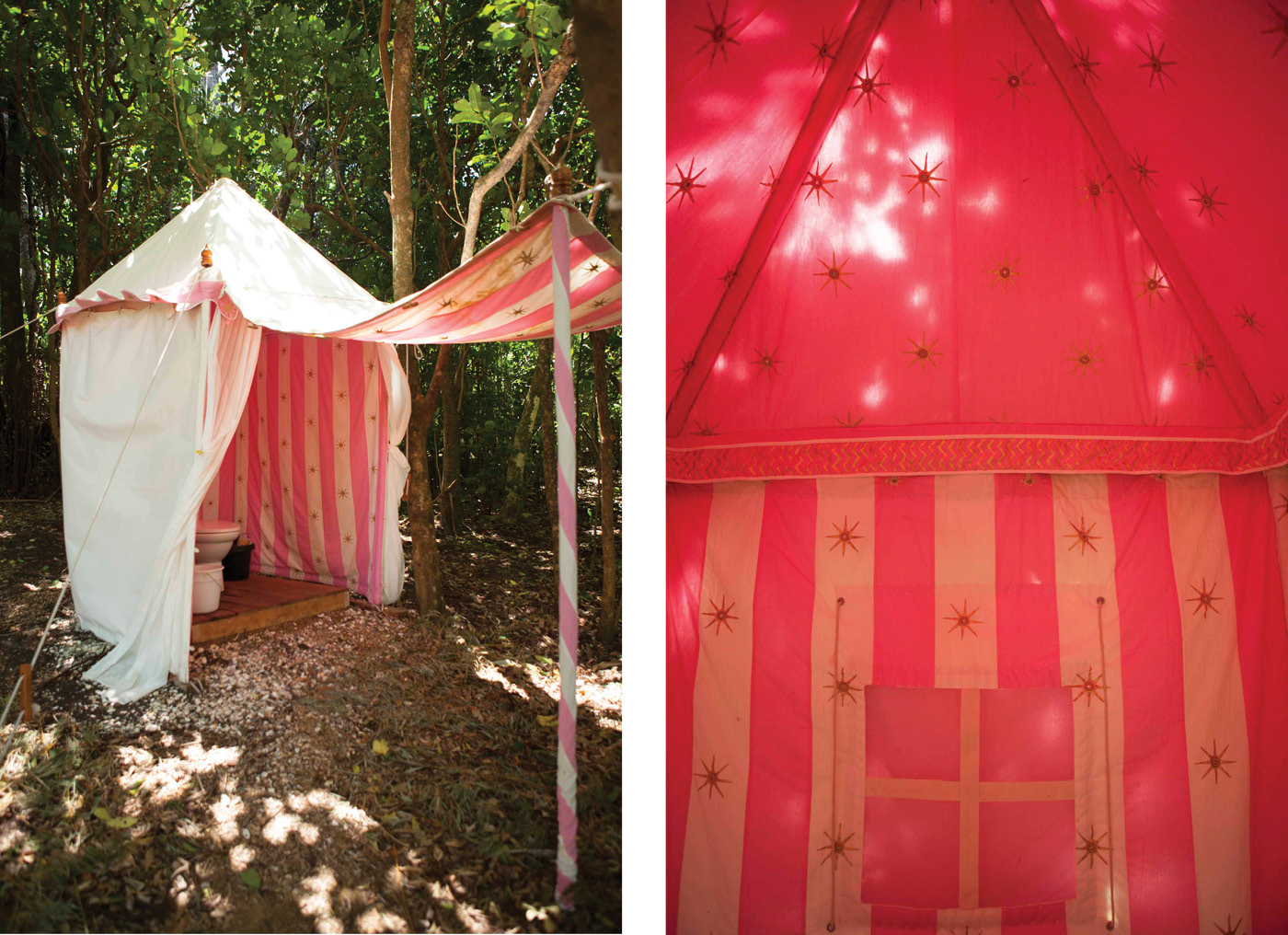

In addition to the container, my parents bought some pretty handmade Indian tents for accommodating guests – “proper, long-lasting canvas, with cotton ropes,” Georgie says. She spent some of her childhood in Africa, where she says “we always had canvas tents with pretty decorative, cotton linings. They have a feeling of deliciousness. They add to the landscape rather than spoil it, like most tents do.”

Adds Greg: “They have height and a wonderful sense of decoration and space. They have all the beauty and loveliness of traditional architecture. This is what we love to make, and what we love to live in.”

The container is completely self-sustaining. It collects water from the iron roof into the tanks. And the power, generated from two photovoltaic panels, is enough to run hot water, a Nespresso machine, radio and fridge and charge mobile phones.

We catch fish and grow our own herbs and vegetables. And if we plant seeds in October and November we have fresh tomatoes and potatoes ready for the long months of summer.

The low-impact approach is entirely deliberate. “We keep building these types of homes because the world’s resources are not inexhaustible and must ultimately run thin,” Greg says. “If you have children then you understand what is precious to the future – everything that we have enjoyed ourselves, and more. Therefore one naturally doesn’t want to waste natural resources, but to conserve them for the benefit of future generations.”

Georgie believes their vision for the site was a result of “over-dosing on concrete and glass and heavy stuff in the ground – it was so lovely to go back to camping,” she says. “We have the luxury of a deck, clean sheets and hot water, but you still have the notion of being outside with the elements. It’s the loveliest way to enjoy a piece of land without intruding on it by pouring concrete into it.”

The pair still has some luxuries. “You have to have a good fridge to enjoy a cold beer or cold wine,” Georgie says. “And we made a proper loo [flushed with buckets of sea water], because that’s what people loathe about camping: long drops. This one is just like sitting on the loo – in fact, it’s better, as you can sit there and look at the sea from the most beautifully decorated tent!”

As a New Zealander, Greg is no stranger to beach living. Georgie was brought up in Africa with what she calls “no feet on”. So after many years in England, they welcomed a return to that kind of lifestyle. “Living on Great Barrier was good training for that. Learning to survive without mobile phones, internet and an endless supply of electricity and water,” Georgie says.

“It’s nice having a phone to keep in touch with the world, but when you’re on holiday you don’t need a television,” says Greg. “You don’t need lights – you can have candles. You don’t need shops nearby. It makes you do all the things you did when you were a kid: spend all day on the beach, gather food, prepare it together, eat together and talk. So long as you’re prepared, you make the most of it and it works very well.” – Florence Noble.

Q&A with designer Greg Noble

HOME When you bought this piece of land, inaccessible by road, how did you decide you were going to inhabit it?

Greg Noble It wasn’t really a decision as such, it was more a matter of opening yourself to the place and to what it was saying. Once you understand it physically, climatically and historically then you begin to understand what is required of your interaction. For example, the place is relatively untouched and isolated in modern-day terms. It has an intimacy and strong sense of enclosure and shelter; it has a long history and meaning to Maori and this will always take precedence over the needs of any current day custodian. These are the priorities that inform one’s feelings of where and how to interact – obviously this means with respect, with a lightness of touch and with a long-term commitment to the regeneration and health of the native flora and fauna.

This is what makes the place the beauty spot it is. If our presence can remain humble but our contribution to its future strong, then for us it becomes another episode that makes life worth living.

HOME How was your experience of creating this off-grid structure?

Greg Noble The people involved in alternative energy systems are enthusiastic and committed. We used S4 Solar who made it economical and almost instant to make your own free electricity from the sun. The components are compact, really good looking and a nice feature – it is current, relevant and exciting.

HOME What do you like about being there?

Greg Noble It’s our link to the real things in life; to the things that matter and which we don’t give time to in the city. We catch and grow our own food, we garden, we enjoy living barefoot. We are trying to give and share rather than take and this feels nice.

Photography by: Florence Nobel.

[related_articles post1=”59390″ post2=”36172″]